Parchment

Parchment, treated animal skins, was the main writing support of the Middle Ages, implemented during the fourth or fifth century up until the fifteenth century, throughout Western Europe.

Method of Preparation

The process of transforming animal skins into a suitable writing material as well as the creation of manuscripts was a time consuming and laborious endeavors. To begin, the procedure commenced with the killing of an animal by stunning – the act of throwing rocks to slaughter the creature. The carcass was then hung upside down to drain the blood from the veins to make an evenly colored sheet of parchment. Before a skin was turned into a suitable writing support, it had to be thoroughly cleaned and dehaired. First, the skin would be washed in water and soaked for several days in a bath of lime solution to loosen the hair follicles. Traditionally, craftsmen would remove the hair by placing the skin over a beam of wood, first using their hands to pull out as much hair as possible before employing a curved, two-handled blade to remove any remnants. This process is called scudding. [1] Then, the skin would be washed again in water and left to dry under tension, stretched on a frame. This was a critical stage in the process for as the skin dried, it sought to shrank. However, stretched tightly on the frame, it could not reduce its surface area. The structure of the skin would change, the fiber network reorganizing itself into thin, highly stressed laminal structure becoming permanent. [2] Parchment making was a physical process that produced a change in the character of the skin as opposed to the modern chemical process of transforming the material. [3] This laborious and time-consuming process, which dates back to the fifth century, is still practiced in modern day.

The sheets of parchment employed in a manuscript are a reservoir of information, providing insight on the types of animals used and the substrates place of origin. Animals such as sheep, calf, and goat were most commonly employed as the skins for parchment and in vast quantities. [4] The types of animals used depended on where the manuscript was created. For instance, parchment made from calf and sheep has been most commonly found in northern European manuscripts, while parchment made from goatskin has been frequently recorded in Italian works.[5] Furthermore, the color and texture of the substrate and the distribution of hair follicles are all characteristics which can help identify the species of the writing support.

Because the process to create parchment was a taxing and greatly expensive production, defective edges or impurities in the skins were often used in the manuscript and frequently left unrepaired. For example, it is common to find on some leaves of a manuscript holes that already existed in the skin at the time the animal was slaughtered. Such holes vary from tiny insect bites to large holes suggesting a tumor or growth on the skin, or an injury to the animal.[6] This is best illustrated in the image entitled, Parchment Skins,

where the top sheet of parchment is shown to contain several holes spread across the upper region as a result of possible growths or tumors. These sheets of parchment are held in the Steven Miller Conservation Library at Van Pelt Library on the University of Pennsylvania’s campus. If a craftsman wrote on this particular sheet of parchment the text of the manuscript would be transcribed around the holes, dividing words due to the labor-intensive process of making parchment and the high cost.[7] Occasionally, the craftsman would embroider such holes in an attempt to distract the reader from such impurities, however this practice was predominantly reserved for manuscripts of higher stature, such as Bibles, or for rich patrons.

Once the prepared skins had been cut into sheets of parchment, the craftsman would group several sheets together to form a quire, also known as a gathering. [8] The quire was the craftsman basic writing unit throughout the Middle Ages. Quires were created in various sizes, but the most common were quires of eight or ten leaves. This is done by folding four or five sheets in two. In forming the quire, the craftsman would decide whether the hair-side or the flesh side of the sheet would face outward or inward. Through the analysis of manuscripts during the Middle Ages, scholars surmise that medieval craftsman preferred to arrange the leaves so that the outside of the quire was a hair-side. It is easy to recognize the hair-side of a leaf: the leaf is darker due to the presence of hair follicles clustered together.[9] For instance, this is illustrated on page 15v of Ms. Codex 273, an Italian manuscript created during the 14th century, where the hair follicles are clustered together in the upper left quadrant of the page.

Before commencing the writing portion, the craftsman would rule the leaves by pricking small holes into the margins of the leaves to follow the horizontal and vertical rulings. Often using a quill pen, the craftsman would first write the portions of text that were in plain ink, leaving blank those areas that would later receive colored initials and titles. Clear evidence establishes that titles and initials were entered only after the ink text had been written.[10] If a manuscript was to include a cycle of illustrations, the illustrations would normally be the last element entered, only after text, titles, initials were completed. The higher the status of a manuscript and the richer the patron for whom it was made, the more complex would be the process of its production and the larger the number of techniques and pigment involved.[11] Writing the text of a manuscript required that the craftsman have an exemplar from which to copy, which would usually be prepared on a wax tablet or scrap parchment. The process of copying manuscripts was a grueling and lengthy task, with either monks or craftsmen working in harsh conditions.

History

The utilization of parchment – processed animal skins – was predominantly employed as the main writing support during the Middle Ages.[12] However, legends and references to the substrate in literary texts suggest that it may have been employed several centuries earlier than physical evidence dictates. According Raymond Clemens & Timothy Graham, the creation of parchment is attributed to King Eumenes II of Pergamum dating the implementation of the substrate to the second century BC.[13] In contrast, other scholars, such as Robert Deibert, stray away from delineating the first recorded use of parchment, highlighting the uncertainty of when humans transformed animal skins into a writing source, by blanketly stating that parchment was employed sparingly during the fourth and fifth centuries.[14] Nonetheless, historians and scholars concur that parchment was utilized as the principal support for writing beginning in the fifth century after the fall of the Roman Empire until the advent of paper in the fourteenth century.

The rise of parchment as the paramount writing source during the Middle Ages can be attributed to a variety of factors, such as the demise of the Roman Empire in the fifth century C.E. From 27 B.C.E. to 476 C.E., the Roman Empire reigned throughout the Mediterranean world, including Western Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa. [15] During this period, papyrus was the most widely used writing support in the ancient world, spreading from Egypt to the Greek and Romans empires, and to Europe. In its zenith, the Roman empire governed itself through the administration of a literary bureaucracy among which communication rested significantly on light-weight papyrus rolls, easily transported on a highly efficient network of roads. [16] Because papyrus was grown almost exclusively in Egypt, the substrate was suddenly no longer an obtainable commodity when the Roman Empire collapsed due to its origin, the disintegration of trade routes, decrease in quantity, and the high costs of importation.[17] Thus, Western Europe and former Roman territories sought to find another writing support.

In conjunction with the fall of the Roman empire, the rise of the Roman Catholic Church assisted in the proliferation of parchment throughout the Middle Ages. The disintegration of Imperial authority in Rome created an absence of power throughout Western Europe, which allowed for the Roman Catholic Church to seize control of the city.[18] Because early Church fathers and missionaries preferred parchment over papyrus, due to the substrates durability and abundance, the writing support began to be employed despite the widespread use of papyrus.[19] Archeological evidence of the earliest Christian Bible codices - manufactured out of animal skins – from Egypt supports this preference while also highlighting the way in which these two substrates coexisted. [20] While the Christian community was nearly alone in this choice, their rationing to employ this substrate proved to be successful. [21] For instance, the parchment codex was more suitable for easy reference than the cumbersome, fragile papyrus scrolls and the substrates durability proved to travel longer distances and survive varying climates. [22] Thus, parchment became the medium of choice for the Christian religion due to the substrate’s functionality.

Due to the rise of Christianity and the Roman Catholic Church, parchment and papal-monastic network formed a symbiotic relationship beginning in the early Middle Ages: monasteries were self-contained islands of literacy and centers of knowledge.[23] Since a majority of the human population was illiterate, the clergy became the sole custodians and suppliers of written information.[24] Because the reproduction of written information was employed on parchment, the writing support became inextricably linked with Christianity, solidifying its important status and sanctity. This is best illustrated in the writings of St. Benedict and Cassiodorus. The authors outline the idea of the monastic scriptorium and portrayed book copying as a sacred act, forging a close connection between the ability to read and the religious life of a monk.[25] As a result of this affiliation, the monastery integrated the means – a library, a school, a scriptorium – in order to produce manuscripts. Simultaneously, monasteries manufactured parchment from the skins of their own livestock or those from the surrounding farms, seizing control of the substrate’s production.[26] As a result, monasteries possessed the unique ability to control the manufacturing of books from conception to production. Furthermore, as monasticism spread throughout western Europe during the Early Middle Ages, the quality of parchment was affable to the agrarian and rural location of monasteries, while the materials needed for the production of manuscripts – animal skins and goose quills for pens – were abundant in the woods and valleys of western Europe. [27] These factors contributed to the dissemination of the substrate, even after monasteries lost total control of reproduction, for parchment proved to be a well-suited medium throughout the Middle Ages for its durability and plentitude. [28]

From the fall of Rome to the twelfth century onward, the Church controlled the reproduction of literary texts written on parchment, focusing solely on the manufacturing of religious manuscripts. However, a profound social transformation began to take place as secular literacy rose among the urban populations, and in particular among secular administrators.[29] Centers of knowledge, such as universities, requested for the reproduction of non-religious texts in order to educate the new literate class. As the demand increased, universities began to hire professional craftsmen to reproduce scholarly texts using parchment as the writing source.[30] The establishment of these universities represented a growing “secularization” of learning and education that further undermined the monopoly of knowledge controlled by the monastic orders up until the High Middle Ages.[31]

Secular versus Religious Manuscripts

Ms. Codex 273 is an Italian manuscript entitled, Liber ethicorum Aristotelis, written by Taddeo Alderotti during the 14th century and centers on the teachings of Aristotle’s theories on ethics.[32] This 700-year-old manuscript is bound in an ornately carved, dark brown Morocco leather, originally adorned with gilt rondels and clasps which have since been lost. While the content of the manuscript orients itself during the 14th century, there are several features which indicate that reparations have been enacted during the 15th century. For instance, the encasement of the manuscript is presumed to have been replaced in 1450 with the current Morocco leather. In addition to this, the first page of the manuscript is reported to have been lost or mutilated and, as result, replaced by another leaf in about 1450. The librarians working in the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts at the University of Pennsylvania – where the manuscript is currently held – suggest that the difference in handwriting styles on the first page from the entirety of the manuscript is an indicator of the first page’s replacement. Through visual analysis, the librarians conclude that the primary page is written in a rough hand while the rest of the pages are inscribed in large gotica cancelleresca script. Furthermore, even though there are no concrete explanations as to why the first page and binding of the manuscript were replaced, one might infer that structural damages, possibly due to heat, water, or light, could warrant a repair. By observing the formal qualities of Ms. Codex 273, the librarians were provided with a more precise understanding of the manuscript, the time in which it was created, and its historical context.

-

Cover of Ms. Codex 273

-

Page 1r of Ms. Codex 273

-

Page 2v of Ms. Codex 273

-

Page 3r of Ms. Codex 273

-

Page 66r of Ms. Codex 273

-

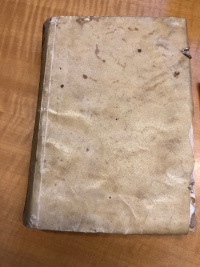

Cover of Ms. Codex 1053

-

Page 1r of Ms. Codex 1053

-

Page 2v of Ms. Codex 1053

-

Page 8v of Ms. Codex 1053

This idea is further exemplified in the investigation of the manuscript’s date of origin. According to the librarians at the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts, Ms. Codex 273 was written in Italy, presumably before 1356. The librarians assert that the work was written before 1356 because of the inaccurate content on page 66r. [33] In this specific passage, the writing lists the names of various lay princes who held electorship. However, a decree known as the Golden Bull of 1356, issued by the Holy Roman Emperor, Charles IV (1316-1378, explicitly names in the document the newly selected Prince – electors, rendering the list in Ms. Codex 273 to be outdated. As a result of this close textual analysis and recording of past historical events, the manuscript’s date of conception is narrowed.

The physical appearance of the parchment sheets provides a great amount of context on the creation of the manuscript. After several blank flyleaves, the first page of written text, 1r, is inscribed with a red inked heading, which immediately calls attention to the viewer for the inscription’s use of color and its separation from the illuminated paragraph below. Shortly after, the viewer’s gaze shifts downward to the bottom half of the page where a short column of text, containing ten lines, revolves around the paragraph’s first letter – “O” – which is drawn in red and blue ink. According to Raymond Clemens and Timothy Graham, the two most commonly used colors for initials during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries were red and blue ink.[34] Clemens and Graham assert that many initials would include both colors, as exhibited on the 1r and 3r, and extend into the margin where a decoration would be depicted.[35] This is exemplified on page 3r of the manuscript where the letter “L” is written in red ink with blue decorations expanding into the margin. In the subsequent pages, initialed letters follow an alternating pattern: a red initial follows a blue initial and vice versa. In addition to the beautiful illuminations and initialed letters, the rulings, created by the craftsman before writing commenced, are easily viewable when examining various pages. Specifically, on page 2v, light straight lines are noticeable underneath the text, acting as a frame. The use of colored inks and inclusion of ornate drawings suggests that this secular manuscript was important and highly valued. Furthermore, because of the substrates ability to retain a variety of pigments for centuries, artisans have been given the ability to showcase their crafts transforming the text of the manuscript into a work of art.

Recognizing the species of parchment depends on the color, hair, and texture of the sheet. When touching the manuscript, the texture of the parchment sheets feels thick and crisp, and in certain areas, appear to contain a glossy coating. The thickness of the pages can be attributed to the suspected animals employed for the creation of this manuscript. While the librarians at the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts have established a specific origin and date for the creation of this manuscript, they have yet to define the type of animals employed. However, the viewer can surmise that the sheets of parchment were made from the skins of goats due to Italy’s abundance of this species. As such, parchment of Italian origin is claimed to be thicker and more rigid than parchment created from other animals, such as calves. For example, parchment made from calfskin tends to be whiter or creamier in color, rendered soft to the touch, with little to no difference between the hair side and flesh side.[36] In contrast, parchment prepared from sheepskin or goatskin is often yellowish in color, may be somewhat greasy or shiny, and thicker.[37] Furthermore, when peering closely at the sheets of parchment, such as page 3v, the hair follicles of the animals used can also be seen. At a first glance, the sheet of parchment appears to have areas of discoloration in the upper left corner of the page. However, when taking a closer look, it is evident that these areas of discoloration, darkening the page, are due to clusters of hair follicles. When reviewing the entire manuscript, stains or discoloration can be seen around the edges of the sheets most likely due to fingerprints suggesting that this work was read frequently.

Ms. Codex 1053 is a manuscript entitled, Biblia Sacra, written by an unknown author during the 13th century.[38] This 800-year-old work is bound in an elaborately carved leather skin and adorned with two braided leather ties on the lower cover of each volume. The librarians working in the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts at the University of Pennsylvania – where the manuscript is currently held – surmise that the work was created during the 13th century in England. The Biblia Sacra is comprised of the Bible in two volumes, – the Old and New Testament – the Interpretation of Hebrew Names, and a highly abbreviated chapter lists for both the Old and New Testament.

Through visual analysis, the librarians are able to critically observe the physical features of the manuscript, illuminating significant attributes or anomalies in the creation or content of the work. This idea is best illustrated in the physical layout of each book within the manuscript. Because the manuscript is broken up into three separate parts, the size and number of columns greatly differ from one another. For instance, the Bible is written in two columns of fifty lines while the Interpretation of Names is written in three columns of fifty lines. As a result, both sections stand in stark contrast to the chapter lists which are written in three columns of forty-six to forty-nine lines. Furthermore, in order to delineate the beginning of each book, the craftsman has inserted puzzle initials with decorations to call the reader’s attention. The decorative tool known as a puzzle initial is derived from the idea that the letter resembles two puzzle pieces fitting together. On the first page of written text, 1r, the puzzle initial commands the viewer’s attention as a result of the vibrant colors – red and blue ink – and its enlarged size. Thus, the large and colorful letter stands in stark contrast to the dark text which fills a majority of the page. Throughout the manuscript, the puzzle initial is consistently employed in addition to red and blue inked decorations, initialed letters, titles, and chapter numerations. When taking a closer look at the use of color throughout the manuscript, specifically on page 2v, the viewer can see that the initialed letters follow an alternate pattern, switching from red to blue ink and vice versa. The colored ink adds an aesthetic beauty to an otherwise long and bland page of text. This notion is further supported as the viewer continues reading. The decorations and illuminated initials adorn a majority of the pages and allow for the manuscript to come to life. Despite the distinctions in each book to individualize one another, efforts have also been made to preserve a cohesive structure. For example, the style of writing known as gothic script remains constant throughout the entire manuscript. The use of parchment in this manuscript is not only to contain and disseminate knowledge, but also functions as a space for artistic endeavors.

In contrast to Ms. Codex 273, the viewer is scarily able to see hair follicles as well as the rulings employed by craftsmen on the pages of Ms. Codex 1053. These differences in both physical and visual characteristic may be attributed to the fact that Ms. Codex 1053 is a religious text, highlighting the notion that manuscripts of higher stature were given a greater attention to visual aesthetics.[39] This notion is further exemplified in Ms. Codex 236, a Bible also entitled, Biblia Sacra, created in the 13th century in northern France. [40] Both Bibles were produced in the 13th century, however Ms. Codex 236 is much larger, features more ornate decorations, including representations of religious figures, such as Adam and Eve, and employs a variety of inks. In contrast to Ms. Codex 1053, which is comprised of 71 leaves and includes two colors, – red and blue ink – Ms. Codex 236 is made up of 465 leaves and incorporates red, blue, green and gold inks to transcribe the Old and New Testament, Interpretations nominum hebraicorum, the Prayer of Manasseh, a calendar of the Church year, a missal, and a breviary. When opening Ms. Codex 236, a manuscript bound in 18th century French morocco leather, the viewer is presented with the Interpretations nominum hebraicorum inscribed in red, blue, and black ink. On the first page, 2r, the letter “A” is illuminated in gold, blue, and black ink on the upper left corner of the page with decorations extending into the margins. Compared to Ms. Codex 1053, the illuminations in Ms. Codex 236 are more detailed and increase in number. Specifically, on page 28r, these notions are highlighted by the ornate illustration of a monk writing in his scriptorium, calling attention to the act of writing and the individuals who produced such works. As highlighted before, monasteries were the sole custodians and suppliers of written information up until approximately the 12th century. Thereby, during that time, writing and copying were portrayed as an exclusive and privileged act, transforming the monastery into a sacred and elite place. This illustration of a monk, draped in a blue cloak, as he sits before a two-toned brown and blue aisle, signals not only the self-reflexivity of the illustration, but also the sanctity of the words and the physical manuscript itself. This square illustration, filled in with gold ink, is part of a larger decoration which extends to approximately the bottom of the 50 lined text. Similar to Ms. Codex 1053, Ms. Codex 236 employs illuminated initials as seen on page 28r, however, the initial depicted on this page is grander in scale and embellishments. The enlarged and highly detailed letter, “J” commands the viewers’ attention for its placement and use of colors, standing in stark contrast to the French Gothic script written in black ink. The illuminated initial employs a variety of colors – blue, white, brown, and gold ink – and its large size functions as a border for the left side of the page. Furthermore, the complex decoration includes not only a representation of a monk, but also zoomorphic designs. Even though the illustrations between the two manuscripts differ, the layout and a few visual attributes of both Ms. Codex 1053 and Ms. Codex 236 contain similarities, in terms of the double columns, and the red and blue inked headings and titles. The parallels between the two manuscripts of different origins alludes to the fact that may have been a rubric followed by the creators. Furthermore, it is interesting to note how the layout of the physical page differs between secular and non-secular texts. For example, the text in both Ms. Codex 1053 and 236 are written in two columns which is a characteristic of both manuscripts’ structure, while the text in the Liber ethicorum Aristotelis is written in one column. The comparison of such texts illustrates the ways in which content shapes the physical structure of the page and, on a larger scale, the manuscript. Thus, through the analysis of such works, the viewer is provided with a great understanding of the ways in which parchment was employed throughout the Middle Ages from religious texts, such as the Bibles selected here, to secular texts, such as the Liber ethicorum Aristotelis.

Conclusion

Through the research and examination of several manuscripts created during the Middle Ages, the viewer is exposed to the ways in which parchment, the favored writing support of the time, contains not only the written words transcribed on the page, but also material history. For instance, the production of parchment and, more broadly manuscripts, relied upon an extraordinarily rich social fabric: craftsmen, parchmenter, binders, illuminators, farmers, miners, merchants, and scholars. It also relied upon a society that consumed books: monks, priests, humanists, and the men and women who made up medieval civilization.[41] In other words, both parchment and manuscripts are a time capsule that reveal the social, political, and historical trends of the period in which they were created and produced. Thus, as a result of the extensive research on parchment manuscripts, historians, scholars, scientists, and individuals in many other fields have been able to establish the date, provenance, usages, and authenticity of the written works. More specifically, research has also shown the ways in which parchment has been implemented beyond a writing support. For instance, Vincent Ferrer’s 16th century manuscript entitled, Sermonum Sancti Vincentij ordinis predicatorum de temporiis estivalis (SC V7438 515s), illustrates how parchment also functions as a cover, protecting the printed pages inside.[42] The thickness of the parchment highlights the substrate’s formal qualities, – its durability – suggesting a reason why the craftsman may have selected this material to bound the work. Furthermore, it is interesting to note that this manuscript is printed on paper, suggesting that the two substrates – parchment and paper – coexisted even after the advent of the printing press in 1440, similar to the way in which papyrus and parchment originally coexisted. The process of collecting and archiving works, such as SC V7438 515s, Ms. Codex 273, 1053, and 236, in conjunction with the continuous analysis and research of manuscripts provide insight into the cultural ideologies, economy, and societal roles at the time of creation.

Notes

- ↑ Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007, p.10

- ↑ Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007, p. 10-12

- ↑ Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007, p. 9

- ↑ Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007, p. 9

- ↑ Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007, p. 9

- ↑ Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007, p. 13-14

- ↑ Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007, p. 12-13

- ↑ Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007, p. 14

- ↑ Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007, p. 14-15

- ↑ Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007, p. 17-18

- ↑ Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007, p. 19

- ↑ Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007, p. 9

- ↑ Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007, p. 9

- ↑ Deibert, Ronald J. Parchment, Printing, and Hypermedia: Communication In World Order Transformation. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997, p.53

- ↑ Deibert, Ronald J. Parchment, Printing, and Hypermedia: Communication In World Order Transformation. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997, p. 53

- ↑ Deibert, Ronald J. Parchment, Printing, and Hypermedia: Communication In World Order Transformation. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997, p. 52

- ↑ Deibert, Ronald J. Parchment, Printing, and Hypermedia: Communication In World Order Transformation. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997, p. 55

- ↑ Deibert, Ronald J. Parchment, Printing, and Hypermedia: Communication In World Order Transformation. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997, p. 54

- ↑ Deibert, Ronald J. Parchment, Printing, and Hypermedia: Communication In World Order Transformation. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997, p. 54

- ↑ Deibert, Ronald J. Parchment, Printing, and Hypermedia: Communication In World Order Transformation. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997, p. 54

- ↑ Deibert, Ronald J. Parchment, Printing, and Hypermedia: Communication In World Order Transformation. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997, p. 54

- ↑ Deibert, Ronald J. Parchment, Printing, and Hypermedia: Communication In World Order Transformation. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997, p. 54

- ↑ Deibert, Ronald J. Parchment, Printing, and Hypermedia: Communication In World Order Transformation. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997, p. 55

- ↑ Deibert, Ronald J. Parchment, Printing, and Hypermedia: Communication In World Order Transformation. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997, p. 55

- ↑ Deibert, Ronald J. Parchment, Printing, and Hypermedia: Communication In World Order Transformation. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997, p. 54

- ↑ Deibert, Ronald J. Parchment, Printing, and Hypermedia: Communication In World Order Transformation. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997, p. 54

- ↑ Deibert, Ronald J. Parchment, Printing, and Hypermedia: Communication In World Order Transformation. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997, p. 55

- ↑ Deibert, Ronald J. Parchment, Printing, and Hypermedia: Communication In World Order Transformation. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997, p. 54

- ↑ Deibert, Ronald J. Parchment, Printing, and Hypermedia: Communication In World Order Transformation. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997, p. 62

- ↑ Deibert, Ronald J. Parchment, Printing, and Hypermedia: Communication In World Order Transformation. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997, p. 62

- ↑ Deibert, Ronald J. Parchment, Printing, and Hypermedia: Communication In World Order Transformation. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997, p. 62

- ↑ Taddeo Alderotti, Ms. Codex 273, Liber ethicorum Aristotelis, 14th century, from the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania. Photo by the University of Pennsylvania. Permanent Link: http://hdl.library.upenn.edu/1017/d/medren/9915517913503681

- ↑ Taddeo Alderotti, Ms. Codex 273, Liber ethicorum Aristotelis, 14th century, from the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania. Photo by the University of Pennsylvania. Permanent Link: http://hdl.library.upenn.edu/1017/d/medren/9915517913503681

- ↑ Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007, p. 27.

- ↑ Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007, p. 27

- ↑ Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007, p. 7

- ↑ Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007, p. 7

- ↑ Ms. Codex 1053, Biblia Sacra, 13th century, from the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania. Photo by the University of Pennsylvania Permanent Link: http://hdl.library.upenn.edu/1017/d/medren/9940245653503681

- ↑ Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007, p. 29.

- ↑ Ms. Codex 236, Biblia Sacra, 13th century, from the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania. Photo by the University of Pennsylvania. Permanent Link: http://hdl.library.upenn.edu/1017/d/medren/9915517913503681

- ↑ Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2007, p. 30

- ↑ Vincent Ferrer, SC V7438 515s, Sermonum Sancti Vincentij ordinis predicatorum de temporiis estivalis, 16th century, from the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania. Photo by the University of Pennsylvania.