Perpetual Card: Vaticinia Varia

Perpetual card: Vaticina Varia is a manuscript hand-written by an unknown author, detailing various fortune telling methods and astrological conventions. The name perpetual card means a perpetual calendar, sometimes also called an infinite calendar. This manuscript contains a calendar for the year of 1688, explanations on how to calculate the date for feasting and traditional holidays, as well as extensive examples and notes on astrological predictions. Perpetual card approaches the art of fortune-telling through numeric calculations, Christian traditions, and astrological observations. This manuscript was originally collected by the Henry Charles Lea Library, and now stored in theKislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts at the University of Pennsylvania.

Manuscript Structure

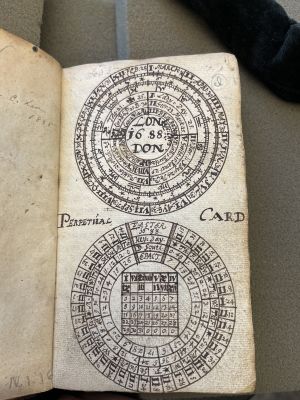

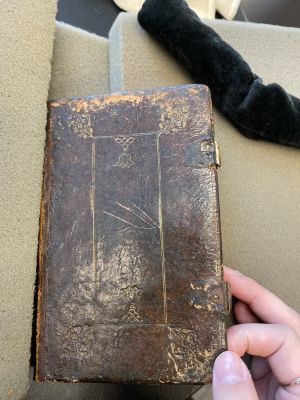

The book begins with a title page of a circle illustration with the words “London 1688” written in the middle (see photo 1.1). Numbers and dates surround the words in the middle. It is thus inferred that the manuscript was written in the year 1688, in London. However, this may not necessarily be the time that this manuscript was bound together into a notebook with gilt calf. From eye observation, the calf binding appears to be from a much newer date (see photo 1.2).

There is a possibility that the book may have been rebound again by the collector or later readers. The patterns on the calf are delicately pressed and adorned with gilt. On the right side, there appear to be two metal locks, perhaps purposed for locking the content of the book away from common readers. Whether these locks were initially created to be functional or ornamental remains a question. If these locks were functional, they, in part, reflect the nature and history of astrological fortune-telling. Manuscripts like these were not written for the masses but rather for a small number of people who studies the occult. The methods and calculations for astrological predictions were largely exclusive to certain groups of people and not easily accessible. At its present stage, the metal locks do not appear to retain any particular purpose (i.e. locking up the text).

Another clue to why the manuscript may be written and bound at different time periods lies in the pattern of the marbled paper glued between the outer calf layer and the first page. This manuscript begins and ends with sheets of delicately-created marbled paper, consisting of deep red, sky blue, white, and light yellow oil colorings. This marbled paper is made in the nonpareil pattern, which was seen predominantly in 19th and 20th century. One theory could be that the manuscript was first written in 1688, but later bound together into a notebook with a nice calf book cover by a collector, one or two centuries later. The date indicated on the title page possibly does not match that of the cover and the marbled paper.

The entire manuscript consistently employs brown or black colored ink to write notes, to draw astrology patterns and signs, as well as to outline and shade themed illustrations.

Book Content

This manuscript tackles a diverse range of topics, demonstrating methods of astrological calculations and predictions that require prior knowledge in the field.

The entire manuscript was numbered by its author in terms of pages. It begins with some handwritten notes in English, explaining in detail how to use the perpetual calendar to calculate festivals and important dates of a year, including the date for Easter and for feasts. The first twelves pages of English notes are separated from the rest of the book, marked from “i” to “xii”. After the introductory notes, the manuscript officially begins on page “1”. Starting from this page, the writer turns to using Latin as the language of communication.

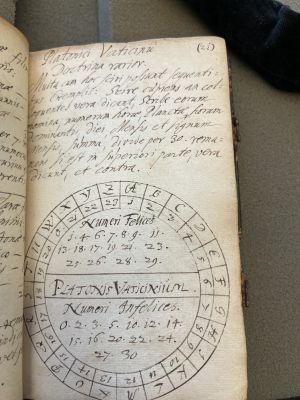

The writer then dedicates a large amount of time in the following pages to explain a fortune-telling technique that relies on numeric calculation. From page 1-55, the author creates many signature circle illustrations containing the alphabet of 26 letters. In these circles, each letter is assigned a number. The number is not fixed, but seems to be dependent on a case-by-case basis. The method of assigning numbers to letters is unknown. On every page that contains a signature circle illustration follows example calculations done by the author. The author demonstrates how to implement this method of numeric prediction, adding together the values assigned to each letter of a person's name.

Eventually, as the manuscript progresses, more elements are added to the circle, including archangels, the twelve horoscope signs, Latin phrases, and the classical planets (see photo 1.7). Though not any illustrations of this exact fashion could be discovered online, associations can be made between this manuscript and the work of earlier occultists such as John Dee and Johannes Trithemius, whose work also employs extensive numeric calculations, knowledge of Christian traditions, and a similar circle illustration pattern.

Beginning on page 56, the manuscript lists a calendar-like table with various signs representing the classical planets. A similar form is seen on page 64 where different numbers are also incorporated onto the table (see photo 1.8). The meaning and function of these tables remain rather elusive. It is interesting to note that at the top of the page, the author lists the names of four European languages: Dutch, French, English, and Latin. Starting from page 70, the author starts drawing out patterns that seem to have significance in the art of fortune-telling and astrology studies. On page 71, a sun and a phoenix being reborn in the fire can be spotted on the page. It can be concluded that these methods of astrology are very much based on a Christian belief(see photo 1.9). The story of Adam and Eve is also hand-drawn in the manuscript (see photo 2.0). The drawing utilizes lines to serve as shading and create a sense of 3D space within the 2D paper. It would be interesting to further explore the relationship between Christianity and astrology during that period: were astrology supported by the church or condemned by it?

The manuscript continues to delve further into different techniques of fortune telling throughout the rest of the book. While most words remain hard to decipher, some Latin phrases could be translated to understand the illustrations. For example, on page 102, Latin words such as life, fortune, and health disclose the purpose of these circle illustrations (see photo 2.1). The author is using some form of numeric calculation to help predict the life path of various individuals.

It may be suspected that this manuscript is intended to serve as a guide for those who may hope to learn more about astrology, fortune-telling, or just to use basic methods to help oneself identify lucky numbers and relevant astrological observations. This is because, at the end of the manuscript, the author dedicates a section explaining, through concise illustrations, the numbers and icons relevant to the twelve horoscopes (see photo 2.2). The graphic nature of these pages indicates that it was meant for an audience, not just for record-keeping purposes for the writer. The page number ends on 193. However, additional blank pages were added and pencil marked page numbers continued. This time, a different handwriting continued the manuscript by writing some English notes relevant to astrological observations. The handwriting is distinctively different because the writer employs a completely different method of writing the letter “f” (see photo 2.3). The existence of such notes meant that this notebook was passed around by different people, and potentially purposed to be a guide being distributed among astrology enthusiasts. The manuscript ends with several blank pages, almost as if it was compiled together for future readers to add in further notes. Eventually, the readers reach the closing marbled paper and back cover.