Formulary.: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

=== The physical book === | === The physical book === | ||

The book is a traditional codex, and its covers are made of contemporary leather, detached from the folium. The spine is lacking. As for the pagination, there are 263 (paper) leaves, making up 526 pages. Pages 420-482 are blank, as well as pages 500-526. The author, Ingersoll, and perhaps other contributors, used ink, whereas the modern writing, such as the page numbers, is in pencil. The book is laid out via a left vertical bounding line ruled in ink. | The book is a traditional codex, and its covers are made of contemporary leather, detached from the folium. The spine is lacking. As for the pagination, there are 263 (paper) leaves, making up 526 pages. Pages 420-482 are blank, as well as pages 500-526. The author, Ingersoll, and perhaps other contributors, used ink, whereas the modern writing, such as the page numbers, is in pencil. The book is laid out via a left vertical bounding line ruled in ink. | ||

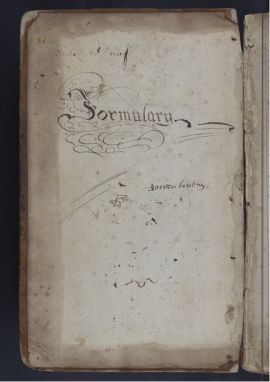

[[File:Front Cover.jpg|270px|center|Front Cover]] | |||

==== Wear ==== | ==== Wear ==== | ||

There is much evidence of wear on the book, perhaps on account of its age as well as multiple contributors. Additionally, the formulary was probably referenced over and over again within the American legal system, which is extremely formal and rule-based, necessitating that lawyers adhere very closely to form templates. Evidence of the wear can be seen in various places. First, the outside of the book: the cover is warped and edgeworn, and the outside binding is missing. Second, the earlier pages are stained and worn. | There is much evidence of wear on the book, perhaps on account of its age as well as multiple contributors. Additionally, the formulary was probably referenced over and over again within the American legal system, which is extremely formal and rule-based, necessitating that lawyers adhere very closely to form templates. Evidence of the wear can be seen in various places. First, the outside of the book: the cover is warped and edgeworn, and the outside binding is missing. Second, the earlier pages are stained and worn. | ||

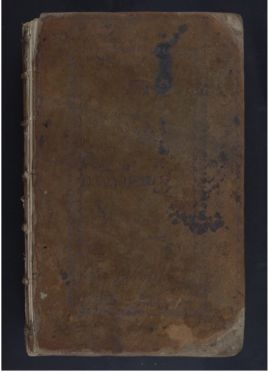

[[File:Back cover.jpg|270px|center|Back Cover]] | |||

==== Marginalia ==== | ==== Marginalia ==== | ||

For the duration of Ingersoll’s writing, the first 151 pages, there is significant use of marginalia. Ingersoll used the marginalia as annotations, where he cited different laws. On page 118, found below, Ingersoll denotes what the form is, a ‘‘Form of a Writ of Entry’’ and references the related laws to the form. In this case, ‘‘Proceedings … Common Recovery the Court’’ and ‘‘Tenant Plea.’’ Therefore, the annotations assist the lawyer in associating the related common law with its civil procedure. | For the duration of Ingersoll’s writing, the first 151 pages, there is significant use of marginalia. Ingersoll used the marginalia as annotations, where he cited different laws. On page 118, found below, Ingersoll denotes what the form is, a ‘‘Form of a Writ of Entry’’ and references the related laws to the form. In this case, ‘‘Proceedings … Common Recovery the Court’’ and ‘‘Tenant Plea.’’ Therefore, the annotations assist the lawyer in associating the related common law with its civil procedure. | ||

Revision as of 21:07, 3 May 2022

Introduction

Jared Ingersoll’s ‘‘Formulary’’ has many implications for legal scholarship. Most importantly, it provides transparency into the practical aspects of how laws were implemented in Early America. While it is one thing to know which laws existed ‘’on the books’’, it is another to see how such laws were actualized. By situating this text in its historical context, legal historians can understand more than just the recorded, established laws, but how laws were able to affect individuals’ lives. Additionally, the book demonstrates the evolution of the legal field by encompassing the legal frameworks for cases that were particularly relevant at the time, notably, ones pertaining to slavery.

Historical Context and Background

Jared Ingersoll

Jared Ingersoll, the proprietor of the formulary, was a famous American lawyer, politician, and a signer of the U.S. Constitution. He was born in New Haven, Connecticut in 1749. His father, also named Jared Ingersoll, was Connecticut’s agent to London and was responsible for enforcing the detested Stamp Act of 1765. The younger Ingersoll followed a different political trajectory as an advocate for American independence just after his graduation from Yale University in 1766. To launch his career as a lawyer, Ingersoll took over his father-in-law’s legal practice during his term as Pennsylvania Governor. Ingersoll was very accomplished in both law and politics, including by taking part in the nation’s founding. In his legal career, he argued many cases, some in front of the United States Supreme Court. Notably, he represented Georgia in Chisholm v. Georgia (1793), a significant case and victory for Ingersoll, in which the Court established its ability to involve itself in interstate disputes and led to the passage of the Eleventh Amendment. Additionally, he litigated in Hylton v. United States (1796), the Court’s first case concerning Judicial Review. Finally, Ingersoll was a significant revolutionary figure. As a well-respected lawyer during the American Revolution, Ingersoll was entrusted to attend the Constitutional Convention (1787), where he argued in favor of a stronger national government and supported replacing the Articles of Confederation with the Constitution. Understanding Ingersoll’s background should make clearer why his formulary is particularly significant; Ingersoll made critical contributions to American law, which may be partly exemplified through his personal form book.

Form Books

There is little literature written about form books, and even less about “formularies,” as the book is entitled. Form books, however, are books comprised of templates lawyers use for different legal proceedings. They prove especially useful in the legal drafting process, where lawyers must emulate the exact language and procedure required by statute. Form books differ in scope, some focused in one area of the law or large multi-volume sets, and others containing a few general legal forms. Ingersoll’s formulary falls into the latter category, as a single, incomplete volume set with few forms here and there. While his form book may have proved useful in legal proceedings relevant to him, its incomplete nature, evident by the dozens of blank pages at the end of the book, indicate that its present value lies in its historical significance more than its practical utility.

Apprenticeship System

Ingersoll studied law through an apprenticeship system, earning his legal degree from Philadelphia lawyer Joseph Reed. The apprenticeship system was the original way in which lawyers earned their bar certifications; students, or apprentices, learned law under the direct supervision of an attorney while performing tasks to assist them. Book historian Arthur Fraas hypothesizes that Ingersoll began writing the formulary in 1778 when he moved to Philadelphia as a young lawyer. The first 153 pages are written in one hand, presumably Ingersoll’s. It is possible that the different handwritings that follow are from Ingersoll’s apprentices, given the alignment with the era of apprenticeship legal education. While proprietary law schools emerged in the 1780s, the apprenticeship system still persisted in the years following. Another piece of evidence supporting this theory is that the latest entry, which is found on page 417, is dated the year 1813, one year after Ingersoll’s death. Clearly, there are multiple authors who may have been his apprentices. Thus, Ingersoll’s formulary serves as a tangible example of tasks assigned to aspiring lawyers in the Early American period.

Material Analysis

Jared Ingersoll’s ‘‘Formulary’’ is a manuscript from the University of Pennsylvania’s Kislak Center for Special Collections cited as Ms. Codex 1628. A digital facsimile to view the manuscript is available from the University of Pennsylvania’s library. While there is no way to know what year exactly Ingersoll began writing the formulary, historians estimate it was in 1778. The Ingersoll family gifted the manuscript to the University of Pennsylvania, where Ingersoll served as an ‘‘ex-officio’’ trustee.

The physical book

The book is a traditional codex, and its covers are made of contemporary leather, detached from the folium. The spine is lacking. As for the pagination, there are 263 (paper) leaves, making up 526 pages. Pages 420-482 are blank, as well as pages 500-526. The author, Ingersoll, and perhaps other contributors, used ink, whereas the modern writing, such as the page numbers, is in pencil. The book is laid out via a left vertical bounding line ruled in ink.

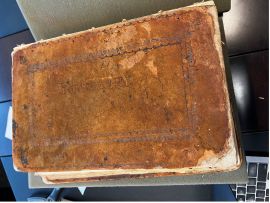

Wear

There is much evidence of wear on the book, perhaps on account of its age as well as multiple contributors. Additionally, the formulary was probably referenced over and over again within the American legal system, which is extremely formal and rule-based, necessitating that lawyers adhere very closely to form templates. Evidence of the wear can be seen in various places. First, the outside of the book: the cover is warped and edgeworn, and the outside binding is missing. Second, the earlier pages are stained and worn.

Marginalia

For the duration of Ingersoll’s writing, the first 151 pages, there is significant use of marginalia. Ingersoll used the marginalia as annotations, where he cited different laws. On page 118, found below, Ingersoll denotes what the form is, a ‘‘Form of a Writ of Entry’’ and references the related laws to the form. In this case, ‘‘Proceedings … Common Recovery the Court’’ and ‘‘Tenant Plea.’’ Therefore, the annotations assist the lawyer in associating the related common law with its civil procedure.

Index

The index, ranging from pages 482-499 is alphabetized only by the first letter and was made after the formulary was compiled. It is an extremely useful feature for seeing what types of law and his practice dealt with. The form templates are highly representative as lawyers likely made templates for procedures they tackled often. While under some letters, such as under “U” on page 499, there are little to no entries filed, under others there are significantly more, such as under the letter “N.” Under “N,” there are many notices, suggesting the practice’s aptitude in contract law. Additionally, some of the notices are filed from courts and uncover Ingersoll’s day-to-day practice.

Significant Content

Slave trade

The formulary had multiple forms pertaining to matters of slavery. In this vein, the evolution of law is apparent, as these forms are presently obsolete following the abolition of slavery. The first page is a template to be used by Philadelphia customs officers to file bills regarding enslaved Africans being brought to Pennsylvania without paying their customs duties. The template calls for the slaves’ seizure.

Livingston v. Swanwick

A notice which provides insight into Ingersoll’s cases is one from the case Livingston v. Swanwick, notifying the two parties that the United States Supreme Court was reviewing the circuit court’s judgment. The only original copy of the notice exists in this manuscript. Fraas hypothesizes that the notice was never sent because the Court did not ultimately hear the appeal.

Pagan v. Hooper

Perhaps the most significant part of the document, for historical inquiry purposes, is the sole copy of a writ of error in the United States Supreme Court case Pagan v. Hooper. The writ of error represents the Supreme Court’s judgment on the case, overturning a ruling of the judicial Court of the Massachusetts Bay.