Songs; Collections of American sheet music bound into volumes by their original owners between 1820 and 1860: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

===Shape-Note Notation=== | ===Shape-Note Notation=== | ||

[[File:Shape_Notes.png|frame|right|The set of seven shape notes, this set shown from ''The Kentucky Harmony'' from Ananias Davison]]Early American music is well-known for developing the innovative, but ill-fated, concept of the shape-note. Using this Western notation-derived concept, note heads on the staff would have a different shape corresponding to their sound in the European solfege system (e.g. do, re, mi). William Little, the first printer to use this notation, is commonly thought to be the founder of this type of musical printing.<ref | [[File:Shape_Notes.png|frame|right|The set of seven shape notes, this set shown from ''The Kentucky Harmony'' from Ananias Davison]]Early American music is well-known for developing the innovative, but ill-fated, concept of the shape-note. Using this Western notation-derived concept, note heads on the staff would have a different shape corresponding to their sound in the European solfege system (e.g. do, re, mi). William Little, the first printer to use this notation, is commonly thought to be the founder of this type of musical printing.<ref> Mayo, Maxey H. ''[https://www.proquest.com/docview/303703292/fulltextPDF/5F6EC19E15DC4DF8PQ/1?accountid=14707 Techniques of music printing in the United States, 1825-1850]'' (MMus). University of North Texas, 1988, p. 60.</ref> While this method limits expression of music using the shape-note format to very tonal Western sounds, it was nonetheless a vital tool to teach Americans with a lower level of arts education to sing popular tunes and hymns. From a printing perspective, this method required event more type sorts, since new type would also be required to represent every different note head used in the system. This method has fallen out of favor to notate pitch, but lives in on percussion notation, where different noteheads denote different percussion instruments. | ||

===Early American Printers=== | ===Early American Printers=== | ||

Revision as of 00:18, 9 May 2023

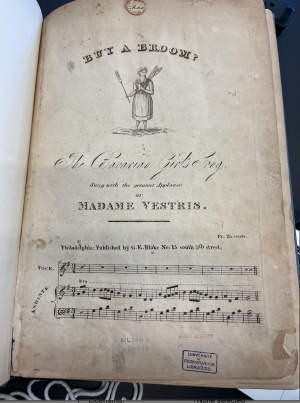

Songs is an anthology comprised of two bound collections of sheet music produced primarily by early American music publishers. Largely representing music printers from prevalent early American cities such as Philadelphia, New York, and Baltimore, the set also contains two works printed in Milan. The collection was originally compiled from an otherwise-unidentified Mrs. Hudson, who lived in a time contemporary with the active period of the printers featured within the books. The collection later passed into the hands of a similarly-unidentified I. Micle, who gifted the anthology to the University of Pennsylvania in 1942. Songs was then accessible through the University's Music Library before being relocated to the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, where it currently resides.

Early American Music Printing

Development of Music Printing Systems

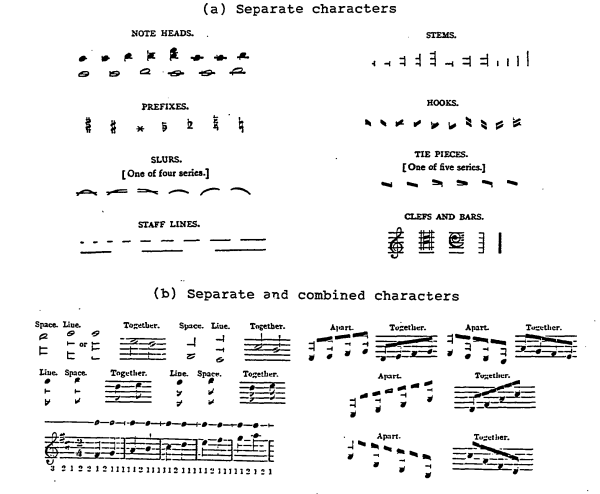

Prior to the 19th century, ink printing of all varieties were often dominated by the usage of moveable type (in which type could be set in an order to create coherent ideas when inked), [1] woodcut (where a desired image was cut out of a piece of wood to create a raise surface for ink to rest on), and intaglio (where a desired image was carved into a metal plate such as copper, where ink could well up).[1] Moveable type was particularly effective for the transcription of written language, while woodcut and intaglio were preferred for image creation. Western musical notation, however, fell in a space between these two categories, which posed issues for a system created with the intention of an alphabet separate from images. Although featuring regularity of note images, the placement of these notes in a 5-bar staff and the connection of these notes via "beaming" prevented the system from easily being replicated piecewise, as moveable type would do, while simultaneously being time-consuming to recreate by hand.

Colonial Era and 18th Century Printing

Printing in this time had not yet developed beyond either moveable type or hand-engraved intaglio; type printing from this time, therefore, requires an enormous quantity of castings to capture the thousands of possible combinations of notes, dynamics, articulation, and phrasing markings. Intaglio marking was done entirely by hand, and although objectively more difficult to read, was prized for individualized expression of the music by the printer's own hand.

Engraved Printing in the 19th Century

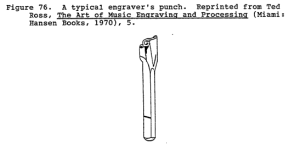

Music printing was revolutionized in 1787 by silversmith John Aitken, who developed a method of merging the spirit of the moveable type with the clearer image associated with intaglio. Pewter (rather than the more expensive copper) plates, pre-engraved with staff lines would be "punched" with musical symbols, enabling a lesser amount of punches (analogous to type), while maintaining continuity of lines across the staff, and the greater definition of lines afforded by intaglio.

While this method was quickly taken up by secular music printers, such as early American printing giants George Blake and George Willig, printers of sacred texts tended to continue using the type-set method.

Shape-Note Notation

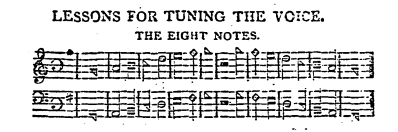

Early American music is well-known for developing the innovative, but ill-fated, concept of the shape-note. Using this Western notation-derived concept, note heads on the staff would have a different shape corresponding to their sound in the European solfege system (e.g. do, re, mi). William Little, the first printer to use this notation, is commonly thought to be the founder of this type of musical printing.[2] While this method limits expression of music using the shape-note format to very tonal Western sounds, it was nonetheless a vital tool to teach Americans with a lower level of arts education to sing popular tunes and hymns. From a printing perspective, this method required event more type sorts, since new type would also be required to represent every different note head used in the system. This method has fallen out of favor to notate pitch, but lives in on percussion notation, where different noteheads denote different percussion instruments.

Early American Printers

Many of the music printers featured within this collection were the largest printers of their time period.

- George E. Blake (1775-1871), advertised in 1803 as owning the Americas' largest music collection, lived above fellow printer John Aitken's printing shop and taught flute and clarinet, before he took own his own shop in 1802. He published secular music, as did most of the printers within this collection, and used the punched-intaglio style that developed following 1787. [3]

- Aitken, by contrast, was a silversmith by trade, not a musician; as a result, he had developed an early start in the music printing and was one of the first to utilize punched engraving, but was soon out-competed by newer printers who were musicians as well as printers (eg. John Christopher Moller, Henri Capron, and Benjamin Carr). [4]

- George Willig, in addition to developing a large musical printing network by himself, was one of the first publishers to develop a family trade of printing. All the above printers were all Philadelphia-based, but Willig's son, George Willig Jr., spread the business via a Baltimore branch taken over from the brother of another famous American printer, Benjamin Carr. [5]

- Benjamin Carr was a London-born printer who was active in Philadelphia and Baltimore, alongside his brother, Thomas. Benjamin Carr is specifically of interest for this collection because the anthology contains a score handwritten for the original owner by Benjamin Carr (the only score in the collection to be featured so). [6]

- Fiot and Meignen were a pair that published music, that arose following the period dominated by the above printers. They were a dominant printer in Philadelphia until their dissolution in 1839, which prompted Meignen to print on his own until 1859, still remaining dominant. [7]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Mayo, Maxey H. Techniques of music printing in the United States, 1825-1850 (MMus). University of North Texas, 1988.

- ↑ Mayo, Maxey H. Techniques of music printing in the United States, 1825-1850 (MMus). University of North Texas, 1988, p. 60.

- ↑ Bewley, John. Philadelphia Music Publishers: George E. Blake (1775-1871). University of Pennsylvania Library's Department of Special Collections. Retrieved on April 7, 2023.

- ↑ Bewley, John. Philadelphia Music Publishers: John Aitken (1744 or 1745-1831). University of Pennsylvania Library's Department of Special Collections. Retrieved on April 7, 2023.

- ↑ Bewley, John. Philadelphia Music Publishers: George Willig (1764-1851). University of Pennsylvania Library's Department of Special Collections. Retrieved on April 7, 2023.

- ↑ Bewley, John. Philadelphia Composers and Music Publishers: Benjamin Carr (1760-1831). University of Pennsylvania Library's Department of Special Collections. Retrieved on April 7, 2023.

- ↑ Bewley, John. Philadelphia Composers and Music Publishers: Leopold Meignen (1793-1873). University of Pennsylvania Library's Department of Special Collections. Retrieved on April 7, 2023.