How to Know the Wild Flowers: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

=== Paratexts === | === Paratexts === | ||

[[File:Contents.jpg|200px|thumb|Table of Contents]] | [[File:Contents.jpg|200px|thumb|Table of Contents]] | ||

| Line 70: | Line 69: | ||

Put more simply, plants complicate the “distinction between content and contents,” contributing to both the physical properties and meaning made by a text.<ref name="Stauffer"/> Indeed, botanical inserts in this volume mimic marginalia in informing both the history of a book’s readership and the ways in which future readers will navigate the text. They also have the potential to make comparably permanent markings on a page, as seen in the offsetting XXXX, in which the specimen has essentially printed itself on the paper. While damaging the book, they themselves are also damaged in the process of being flattened and dried between pages, and they differentiate themselves from marginalia by sustaining more significant transformations over time. By being placed in a book, these biological specimens essentially become cultural objects, further dissolving the opposition of nature and culture addressed by Parsons and her naturalist contemporaries.<ref name="Stauffer"/> | Put more simply, plants complicate the “distinction between content and contents,” contributing to both the physical properties and meaning made by a text.<ref name="Stauffer"/> Indeed, botanical inserts in this volume mimic marginalia in informing both the history of a book’s readership and the ways in which future readers will navigate the text. They also have the potential to make comparably permanent markings on a page, as seen in the offsetting XXXX, in which the specimen has essentially printed itself on the paper. While damaging the book, they themselves are also damaged in the process of being flattened and dried between pages, and they differentiate themselves from marginalia by sustaining more significant transformations over time. By being placed in a book, these biological specimens essentially become cultural objects, further dissolving the opposition of nature and culture addressed by Parsons and her naturalist contemporaries.<ref name="Stauffer"/> | ||

[[File:Funeral.jpg|thumb|220px|Inserted Funeral Announcement]] | [[File:Funeral.jpg|thumb|220px|Inserted Funeral Announcement]] | ||

Revision as of 02:02, 4 May 2023

Introduction

How to Know the Wild Flowers: a Guide to the Names, Haunts, and Habits of our Common Wild Flowers by Mrs. William Starr Dana (illustrated by Marion Satterlee and Elsie Louise Shaw) (1893) was published by Charles Scribner's Sons in New York, NY. The Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts at the University of Pennsylvania obtained a copy of the 1903 reprint edition as part of the Fritz Blank Culinary Archive and Library in 2008. Widely considered the first field guide to flowers issued in America, its publication marked an important moment in the establishment of the genre and the study of natural history in the United States more broadly.[1]

Historical Context

Frances Theodora Parsons

After the death of her husband, William Starr Dana, Frances Theodora Parsons embraced Victorian customs for widows, including the adoption of his name.[2] She also assumed an essentially solitary lifestyle, until her friend Marion Satterlee persuaded her to resume taking walks in the countryside. [2] She then rediscovered the love for botany that she developed while spending her childhood summers away from New York City in Newburgh, New York.[2] Together, the women collected the material for this hugely successful book.[2] Parsons went on to write a column about nature for the New York Tribune (compiled in her 1894 publication According to Season), as well as the successive guide How to Know the Ferns (1899), and a children’s handbook called Plants and Their Children (1896). She gave up naturalist writing when she became very active in the suffrage movement, though she also published a memoir entitled Perchance Some Day (1951) just before her death.[2]

19th-Century Women's Botanical Writings

How to Know the Wild Flowers played a significant role in the American “back-to-nature” movement, led by those concerned about the loss of wilderness with the rise of industrialization and urbanization between 1890 and the early 1920s.[3] Increasing participation in this movement around the country contributed to a more positive attitude towards nature than that which prevailed through much of the 19th century.[3] This led to a rise in “popular botany,” or the study of plants by nonspecialists. [3] Collecting and writing about plants became an especially prominent leisure activity for upper-class women primarily confined to the domestic sphere.[3] Though this began with the rise of the personal “nature essay,” by the turn of the century, field guides by women (especially in the Northeast) were becoming popular too.[3]

As opposed to earlier reference books that described species in technical, scientific language (most notably Asa Gray’s Manual of Botany, which Parsons herself referenced as an alternative model), How to Know the Wild Flowers allowed users with no outside knowledge to identify plants based only on their observations in the field. She cites the following quote, which she came across in a magazine article by celebrated naturalist John Burroughs, as her primary source of inspiration for the work:

- “One of these days someone will give us a hand-book of our flowers, by the aid of which we shall all be able to name those we gather on our walks without the trouble of analyzing them. In this book we shall have a list of all our flowers arranged accordingto color, as white flowers, blue flowers, yellow flowers, red flowers, etc. with the place of growth and the time of blooming.”[4]

These words were so influential to her development of the book’s form that the entire page following the table of contents is allocated to them. With this dedication, she indirectly presents authorship as a collaborative process in which writers build upon the ideas of those before them. Burrough and Parsons must not have been alone in this interest, as the 1893 printing of the book sold out in five days.[5] It went on to receive great praise from figures as prominent as President Theodore Roosevelt and knowledgeable as botanist Frederick H. Knowlton, who wrote in an 1899 review that it had already “undoubtedly done more than any recent book to popularize this delightful branch of natural history."[3]

Textual Analysis

Paratexts

This edition of the book includes two prefaces: “Preface to the New Edition” and “Preface to the Old Edition.” The original section explores Parson’s interest in amateur botany and the development of an accessible guide that differentiates itself from those “keys which positively brushes with technical terms and outlandish titles.”[4] The second focuses entirely on revisions made to the text, including the selection of images and addition of species she since found to fit the criteria outlined in the following section, “How to Use This Book.” These include, most importantly, that flowers are neither unreasonably common nor impractically rare. The extent to which readers are likely to find them beautiful or interesting does not only determine whether they will be included but also how much space and attention they will be given. Justifying her decision regarding the book's length in this section, Parsons explains that it was designed to be “easily carried in the woods and the field.”[4] On the subject of its organizational structure (as proposed by Burroughs), she describes imagining her readers returning from nature walks with flowers to be sorted by color and then identified within each successive section. Finally, she lists the physical materials a reader will find useful throughout this process (a magnifying glass for viewing, a sharp pen knife and needles for dissecting, and a journal for notes) and recommends those expecting a more technical guide turn to Gray’s work instead.

A numbered list of plates identified by the English and the scientific names of their corresponding species follows before the introductory chapter begins. This introduction provides a very brief history of botanical knowledge, including the findings of Carl Linnaeus and Charles Darwin. Parsons then gives a brief lesson on plant biology, outlining a flower’s parts and reproductive systems. A basic glossary of key vocabulary follows in the “Explanation of Terms” section. The list of “Notable Plant Families” and their visible identifiers is the last user feature preceding the body text.

More thorough reference features come after the “Flower Description” chapters, including three separate indexes. The “Index to Latin Names,” “Index to English Names,” and “Index to Technical Terms” each serve as extensions of front paratexts, especially the “List of Plates” and “Glossary.” They also serve as further evidence that Parsons intended the book to be used by a broad audience, including those with and without knowledge of scientific terminology. The book's final section exhibits six full-page publishers’ advertisements for books produced by Charles Scribner’s Sons. The company must have chosen these titles on account of a naturalist audience’s likely interest in them, which is why it is curious that one of these advertisements is for this same edition of How to Know the Wild Flowers. Others are for Parson’s own How to Know the Ferns and According to Season, as well as three books by American author and wildlife artist Ernest Thompson Seton, each featuring excerpted text and quotes from positive reviews.

Body Text

The “Flower Descriptions” constitute the bulk of the book. They are organized into seven chapters by color: White, Green, Yellow, Pink, Red, Blue and Purple, and Miscellaneous. As explained in “How to Use the Book,” species are arranged in each section according to their seasonality, from spring to summer to autumn flowers. The header for each plant description includes its English common name, as well as any other colloquial title it might have. The Latin scientific name and the English family it belongs to are inserted below. The successive text ranges from several sentences to several pages long. It is written in a narrative style, full of literary references and personal anecdotes.

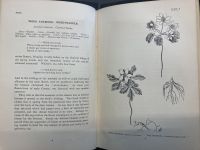

As a customary example from the opening of the book, two pages in the White Flower section are dedicated to the “Wood Anemone,” known colloquially as a “Wind-Flower” and scientifically as an “Anemone Nemorosa.” The verso page is occupied by text, while the recto page includes ink drawings of the plant and its roots at different stages of life. Three lines of this text are committed to the description of its stem, leaves, flower, calyx, corolla, stamens, and pistils. The remainder of the page concerns the specimen’s representation in literature, including excerpted quotes by Victorian poets William Cullen Bryant and John Greenleaf Whittier. Parsons continues to explain that “in the writings of the ancients as well we could find many allusions to the same flower,” including Roman author Pliny’s claim that the flower “opened at the wind’s bidding” and the Greek mythological idea that it sprang from the “tears shed by Venus over the body of the slain Adonis.”[4] Parsons approached many other flowers through such a wide literary lens and quoted celebrated writers ranging from William Shakespeare to Henry David Thoreau throughout the volume. Though today’s field guides include comparable information about where, when, and how to identify each species, this literary element principally distinguishes them from 19th-century women’s field guides, for which this was not irregular.

Imagery

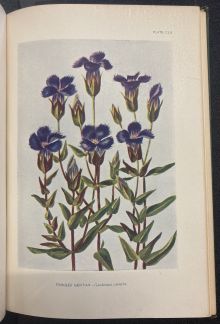

Full-page images are dedicated to 158 species identified in this book. Forty-eight are colored plates designed by Shaw, while 110 are black-and-white illustrations by Satterlee. Each image portrays a single species identified by its English and Latin name in the caption. The level of detail in the pen drawings implies that they were primarily designed to aid a reader’s flower identification process, while the color images may have been included more for aesthetic purposes. As discussed in the “Preface to the New Edition,” these color reproductions are substitutions for Shaw’s original watercolors and also replaced certain black-and-white illustrations. Parsons explains that her new selection of visual representations has “added materially to the book’s actual value as to its attractiveness.”[4]

Material Analysis

Substrate

This standard book contains 546 pages. Its hard front and back covers are 8 inches in length and 5 inches in width. They are covered in green cloth with a floral design, part of which is replicated on the side soft cover. The front and side are lettered in gilt with the title and author’s name. The binding is contemporary with the publication date but has mostly broken from the covers, which serves as evidence of its extensive use. A single sheet of tissue paper protects the book’s first chromolithograph print, though it is unclear why this feature does not accompany any of the many other images that appear in the remainder of the book.

Marginalia

Penciled annotations are prevalent throughout the book. Many take the form of light check marks, presumably signaling that the owner has successfully collected and identified the associated specimen. Others include slightly more information in this regard, including that pictured XXX, which signifies the date (June, 1904) and location (Falmouth, MA) that the Red Baneberry was likely found. These markings are important sources of evidence regarding the history of the volume’s use as a practical reference book.

Insertions

A funeral announcement clipped from an unidentified newspaper is held loosely between the book’s pages. It is for “Miss Clara Wells Lathrop,” who lived from 1853 to 1907, when she died unexpectedly in Northampton, Massachusetts. According to the document, she was an instructor of art at Smith College and had a successful painting career, exhibiting her work in Paris, New York City, Boston, Philadelphia, and Chicago. It states there was a large attendance, especially by faculty and students of Smith College and the Clarke School, where Lathrop previously worked. The storage of the clipping in this volume exemplifies the role of the book as an archive and memorial, especially for items of great sentimental value to their owners. Dried plants are also inserted between pages throughout the book. They are not pasted in but have simply been pressed flat by the book’s weight on pages corresponding to their species’ description. It is unclear when these specimens were collected, but some have lasted in better condition than others. Each has left some visible offsetting on its pages, which serves as another record of the book’s practical use in the field. Though only several plants remain in the volume, it is clear from these yellow outlines that many more were once kept in it.

The history of this collection practice lies in the 19th-century custom of pressing plants into literature books, especially poetry collections. Another effect of the “back to nature” movement, flower pressing had a similar association with femininity.[6] As How to Know the Wild Flowers uses poetry to break down barriers between nature and culture, poetry books began to resemble field guides as users embedded specimens of flowers discussed or illustrated in the text. On the significance of this tradition, material text historian Andrew Stauffer writes:

- “As with marginalia writing… putting flowers in books shapes the writing, publishing, and reading of verse as parts of a continuous network of interactions. Poets wrote knowing that these practices were part of the field of reception; publishers and illustrators designed books that called them forth and echoed them; and readers engaged in this layered scene of reception as they read and marked those books.”[6]

Put more simply, plants complicate the “distinction between content and contents,” contributing to both the physical properties and meaning made by a text.[6] Indeed, botanical inserts in this volume mimic marginalia in informing both the history of a book’s readership and the ways in which future readers will navigate the text. They also have the potential to make comparably permanent markings on a page, as seen in the offsetting XXXX, in which the specimen has essentially printed itself on the paper. While damaging the book, they themselves are also damaged in the process of being flattened and dried between pages, and they differentiate themselves from marginalia by sustaining more significant transformations over time. By being placed in a book, these biological specimens essentially become cultural objects, further dissolving the opposition of nature and culture addressed by Parsons and her naturalist contemporaries.[6]

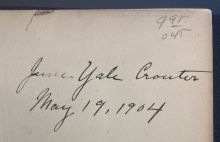

Readership

While the book’s verso front endpaper exhibits Chef Fritz Blank’s modern bookplate, the recto features a written expression of the price for which he (or perhaps an earlier unknown buyer) purchased the book. It also exhibits the signature of June Yale Crouter, written in ink and dated May 19, 1904. Though public information about Crouter is limited, there is a short biography of a woman with this name who lived from 1870 to 1929 in the obituary section of the Report of the Proceedings of the 26th Meeting of the Convention of American Instructors of the Deaf . Several details make for a strong case that this identification is correct. Crouter died in Philadelphia, which helps to explain how Fritz Blank eventually collected the book.[7] More importantly, she served as a teacher of deaf children at the Clarke School of Northampton, Massachusetts.[7] Clara Wells Lathrop’s funeral announcement explains that she also taught there before transitioning to Smith College, and it is entirely possible that she worked at the school simultaneously. Though Crouter was also a professional, her biography closely fits the previous description of upper-class women from the northeastern United States gaining an interest in botanical writing by other women around the turn of the 20th century.

Conclusion

Crouter and Blank were just two of very many 20th-century figures exposed to Parsons’ writing, and clothbound editions of the book remained in print until the 1940s. Various versions of the text, including a Kindle e-book and a print collector’s edition, have continued to be published into the twenty-first century. It is thought that this could be the sole naturalist guide kept in print for over a century, which must be attributed to the literary elements that differentiate it from the many more advanced wildflower identification guides published in more recent years.[5] Yet, this material analysis has shown that no modernized edition could provide the same reading experience as this 1903 copy. Many organizational decisions made by Parsons to ease an amateur botanist’s experience with the text are rendered meaningless in the context of digital media. The act of pressing flowers into a text is also not an option for readers of e-books or even flimsy paperbacks. Parson's goal of increasing accessibility in botanical study, however, is not much different from that of the creators of software like iNaturalist, which provides new sorts of functionality through digital media. In balancing the importance of each of these features, the importance of considering materiality in a comprehensive review of the text is exemplified.

References

- ↑ “How to Know the Wild Flowers: A Guide to the Names, Haunts and Habits of Our Common Wild Flowers.” Drawings and Prints, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/405911.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Anderson, Lorraine. Sisters of the Earth: Women's Prose and Poetry about Nature. Vintage Books, 2003.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Fitzpatrick, John Thomas. “Cultivating and Preserving American Wild Flowers, 1890–1965.” Cornell University, 2006.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Parsons, Frances Theodora. How to Know the Wild Flowers: A Guide to the Name, Haunts, and Habits of Our Common Wild Flowers. Charles Scribner's Sons, 1903.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Raymo, Chet. The Path: A One-Mile Walk through the Universe. Walker & Company, 2003.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Stauffer, Andrew. Book Traces: Nineteenth-Century Readers and the Future of the Library. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Report of the Proceedings of the Twenty-Sixth Meeting of the Convention of American Instructors of the Deaf. United States Government Printing Office, 1929.