Collection of Chinese Culture: Stone Rubbings: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

=== Usage === | === Usage === | ||

These scrolls were most likely used for the preservation of art. Historians or artists themselves must have imprinted the stone engravings onto the paper scrolls as a method for storing or displaying the art in a museum or archive. These scrolls also do not have any marginalia or markings on them, indicating how these pictures were meant to be displayed and respected. The Chinese utilized the scroll as one of the major substrates for paintings due to the multiple ways it could be presented and transported. The images on the scrolls provide information about Chinese culture and art, in particular, topics of interest in religion and beliefs. As part of this large collection, Theodore Bodde must have gifted or bought the scrolls back in China before transporting them to the United States where they would become part of the University of Pennsylvania's Special Collections. | These scrolls<ref name="footnote 3">Li, G.H., et al. “An Automatic Hyperspectral Scanning System for the Technical Investigations of Chinese Scroll Paintings.” Microchemical Journal, vol. 155, 5 Feb. 2020, pp. 1–6.</ref> were most likely used for the preservation of art. Historians or artists themselves must have imprinted the stone engravings onto the paper scrolls as a method for storing or displaying the art in a museum or archive. These scrolls also do not have any marginalia or markings on them, indicating how these pictures were meant to be displayed and respected. The Chinese utilized the scroll as one of the major substrates for paintings due to the multiple ways it could be presented and transported. The images on the scrolls provide information about Chinese culture and art, in particular, topics of interest in religion and beliefs. As part of this large collection, Theodore Bodde must have gifted or bought the scrolls back in China before transporting them to the United States where they would become part of the University of Pennsylvania's Special Collections. | ||

include references + pictures + footnotes/citations (add more references)(fix pictures) | include references + pictures + footnotes/citations (add more references)(fix pictures) | ||

== References == | == References == | ||

Revision as of 00:25, 20 April 2023

These 4 scrolls containing stone rubbings belong to a collection located at the University of Pennsylvania's Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts. The collection contains a total of 9 scrolls consisting of 4 stone rubbings, 4 vertically printed Chinese characters, and 1 lattice filled with Chinese characters. This collection can be accessed here

-

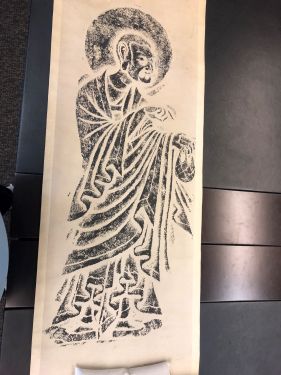

Buddhist Figure with a Halo

-

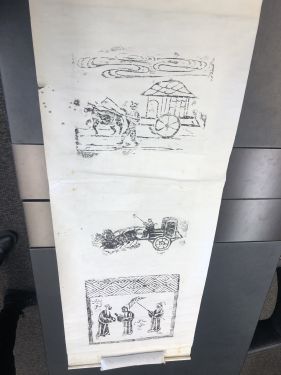

Scenes of Daily Life

Stone Rubbings (Buddhist Figures)

Overview

Of the 4 stone rubbings, 2 of them are Buddhist figures. The Buddhist Figures are vertically imprinted within the scrolls and span across the entire length of the scrolls. One of the Buddhist figures, the one facing the right, pictures a Buddhist with a halo above its head. The Buddhist can be seen wearing a long robe while holding a small pouch in his left hand. The second Buddhist stone rubbing faces the left direction with his hands clasped together in a "praying" motion. This Buddhist has his hair tied up in a bun while also wearing a long robe draped over his shoulders, similar to how a modern-day shawl would be worn.

Historical Context

Both Buddhist figures had a short description/note attached. The note for the Buddhist with the halo read "Rubbing - Buddhist figure with a halo (better face than the other halo figure)" and the note for the other Buddhist figure read "Rubbing of Buddhist figures from T’ien-Leeng-Shen (good quality and condition)". Besides that, the descriptions belonging to the 2 Buddhist figures contained no relevant information about their creator or date of origin. Two other scrolls within the collection belonged to Theodore Bodde, a sinologist (someone who studies Chinese history, language, and culture) who taught at the University of Pennsylvania for many years. Bodde immigrated to the United States during the twentieth century as a Dutch-born electrical engineer. He taught physics at Nyang College in Shanghai, China in 1919. It can be assumed that these scrolls containing the stone rubbings were also under Bodde's possession due to the nature of the scrolls belonging to a collection. This collection was probably either gifted to the University of Pennsylvania or bought by the University of Pennsylvania before/after Bodde's death.

Buddhism is one of the core religions practiced in China. In China, temples and churches commonly had Buddhist statues at the entrances or inside these religious places of worship. These stone rubbings were most likely made from Buddhist statues outside one of these religious temples/churches in China. The scrolls could have been hung inside these religious buildings or stored specifically to preserve the religious culture of Buddhism.

Material

The stone rubbings were imprinted on scrolls, a substrate commonly used in China. The scrolls were made out of two different sheets of paper material. The outer layer was a thick paper-like material, flexible and durable almost like parchment. The inner layer contained the stone rubbing. This layer was softer and flimsier; it makes sense since the paper had to be saturated in water before being imprinted with the stone engraving. These two paper layers, with the outer layer being longer, were glued upon each other. On the left end, the outer layer is wrapped around a thin long rectangular piece of wood, much like a square wooden dowel. On the right end is a long cylindrical wooden rod, similar to a wooden rolling pin. Both materials were extremely light; this made the scrolls easily transported, stored, and accessible. The scrolls were then rolled up from the right end and tied in place with a piece of string/ribbon to protect, store, and transport the contents inside. The thin wooden dowel piece on the left end also had a string embedded in the middle so that the scroll could be hung against a wall.

This format of the scroll with its paper-like substance is contemporary to the region and time period since the Chinese were famous for using paper.[1], a substrate they invented, as their main writing substrate which was often presented in scrolls during the ancient time periods ruled by emperors and kings.

Technique

Stone rubbing.[2] is a technique of engraving calligraphy or images from stones onto paper. This form of preservation and art was very commonly used since the discovery of paper back in China. In essence, the technique of stone rubbing predated the invention of copying machines. The process of stone rubbing started by soaking a piece of rice paper in water; rice paper was desired for its high durability and absorptive properties. After that, the rice paper would be laid across the stone engraving as an ink-soaked cloth is gently pressed against the rice paper, imprinting the calligraphy/image onto the paper. Another alternative to an ink-soaked cloth was a charcoal crayon which was rubbed on the paper against the stone engraving, producing similar results. This technique is quite similar to relief printing. Stone-rubbing techniques have been utilized in China since 420-589 AD during the Southern and Northern Dynasties. As an ancient craft, many people still practice stone rubbing techniques in addition to passing down their knowledge to the next generations to keep the tradition alive.

Usage

These scrolls contain Buddhist figures that have a strong correlation to Buddhism. There are many possibilities for the usage of these scrolls. In the religious context, these scrolls could have been engraved by monks or religious officials as a way to preserve religion on paper. These scrolls could have hung inside temples of worship or stored in an ancient archive. The fact that these scrolls contain no annotations or markings demonstrates the importance of the Buddhist figures and their purpose. These scrolls could have been used for ceremonial purposes such as Lunar New Year or administrative purposes in the preservation of Chinese art and culture. These scrolls also offer insight into Theodore Bodde and his role as a sinologist. It offers information about what Bodde was particularly interested in or what places he visited during his time at Nyang University.

Stone Rubbings (Rectangular Scenes)

Overview

The other two stone rubbings each contain images/scenes vertically imprinted in three rectangular squares. These scenes are evenly spaced along the scrolls respectively. The first scroll contains scenes in order from top to bottom: a meeting of Confucius and his believers, Lao Tzu, and a Buddhist figure. The second scroll contains scenes in order from top to bottom: a man walking beside a horse and buggy, a man riding a horse and buggy, and a public conversation between three individuals.

Historical Context

Similar to the Buddhist stone rubbings, these scrolls also contain short descriptions attached. The scroll on the left (the one with the Buddhist figure) was created in 520-525 during the Cheng-Kuang period. It contains an image of Confucius, a Chinese philosopher whose teachings heavily influenced Chinese culture and education to this day. His beliefs were later transformed into Confucianism which governed a balanced way of life. Lao Tzu was another famous Chinese philosopher who is known as the author of Laozi (later renamed Tao-Te-Ching). He also created Taoism, a set of Chinese traditions and beliefs that emphasize the importance of living a life of balance with the universe. The description for the scroll on the right is written in Chinese. It translates to "The apricot flower is slippery and the rain is in the sound" and "Water Bamboo People" by Xu Shiri 458-131.

The first scroll has many connections with Chinese traditions and religion. It contains images that symbolize core beliefs and values that Chinese people upheld within their culture. The Buddhist figure also denotes how important religion was to the Chinese. This scroll could have been used for educational purposes such as teaching people ideas of Confucianism/Taoism or preservation purposes as a way to record how the Chinese people lived. The second scroll contains scenes that seem to be imprinted off of a stone painting or drawing. We can infer that Xu Shiri was an artist of some sort that drew/sculpted these scenes in stone before it was stone rubbed onto paper. Stone rubbing was another method of preserving art and history.

Material

Materials used to construct these scrolls were the same compared to those of the Buddhist figures. They had a similar structure of 2 paper sheets layered on top of each other, bound to wooden cylinders at both ends. See Materials above for a more detailed explanation.

Usage

These scrolls[3] were most likely used for the preservation of art. Historians or artists themselves must have imprinted the stone engravings onto the paper scrolls as a method for storing or displaying the art in a museum or archive. These scrolls also do not have any marginalia or markings on them, indicating how these pictures were meant to be displayed and respected. The Chinese utilized the scroll as one of the major substrates for paintings due to the multiple ways it could be presented and transported. The images on the scrolls provide information about Chinese culture and art, in particular, topics of interest in religion and beliefs. As part of this large collection, Theodore Bodde must have gifted or bought the scrolls back in China before transporting them to the United States where they would become part of the University of Pennsylvania's Special Collections.

include references + pictures + footnotes/citations (add more references)(fix pictures)

References

- ↑ Tsuen-Hsuin, Tsien. “Chinese Invention of Paper and Printing.” Collected Writings on Chinese Culture, 1 Mar. 2011, pp. 145–162.

- ↑ Catcher, Susan. “The Cicada and the Crow: Chinese Stone Rubbings.” Studies in Conservation, vol. 59, no. sup1, 30 Sept. 2014, pp. 1–4.

- ↑ Li, G.H., et al. “An Automatic Hyperspectral Scanning System for the Technical Investigations of Chinese Scroll Paintings.” Microchemical Journal, vol. 155, 5 Feb. 2020, pp. 1–6.