The American Farmer, Vol. 1: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

The issues are bound using a dense type of cardboard, and the binding is covered with a fabric of tan and white string, with scattered brown stains across the front cover. The interior of each cover as well as the book’s first and last two pages are a unique, relatively thick type of paper that’s almost fully white but with small brown spots mixed in. The main pages are likely [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pulp_(paper) wood-pulp] based, and are darker, very thin, more worn, and have lots of stains and ripples. The text can, in several places, be seen to bleed through to adjacent pages. It altogether consists of 416 pages, plus a title page and a seven-page annotated index titled ‘Contents of Vol. 1’, which includes terms deemed important to the volume’s editor, John S. Skinner. | The issues are bound using a dense type of cardboard, and the binding is covered with a fabric of tan and white string, with scattered brown stains across the front cover. The interior of each cover as well as the book’s first and last two pages are a unique, relatively thick type of paper that’s almost fully white but with small brown spots mixed in. The main pages are likely [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pulp_(paper) wood-pulp] based, and are darker, very thin, more worn, and have lots of stains and ripples. The text can, in several places, be seen to bleed through to adjacent pages. It altogether consists of 416 pages, plus a title page and a seven-page annotated index titled ‘Contents of Vol. 1’, which includes terms deemed important to the volume’s editor, John S. Skinner. | ||

[[File:IMG_2979.jpg|150px|thumb|right| | [[File:IMG_2979.jpg|150px|thumb|right|Annotated index of important terms used throughout the volume]] | ||

The main title page, as well as the headings for each newspaper issue consist of various unique and interesting fonts. The book's headings and page numbers, for instance, reveal that the formatting is consistent with what we would expect from contemporary newspaper issues, by and large. Each page consists of three columns of writing, with articles on generic news relevant to farmers and seasonal advice on specific farming practices comprising the majority of text. However, the newspapers interestingly include a decent amount of illustrations, as well as diagrams, data tables, and legal writing. These illustrations were clearly printed, since they are all flawless, black and white, and were produced at a time and place in which printing illustrations was common. The images and text were likely printed with a newspaper press using [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Relief_printing relief printing]. While Mid-Atlantic America at the time was seeing rapid innovations in printing technology, it wasn’t until the advent of the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rotary_printing_press rotary press] several decades after this volume’s creation that the industry was truly transformed. This text is also a case in point of how, similar to today, newspapers of the time found it in their best interest to squeeze as much information onto each page so as to minimize the costs of tangible inputs like paper and ink in proportion to the value they offer, which is information. | The main title page, as well as the headings for each newspaper issue consist of various unique and interesting fonts. The book's headings and page numbers, for instance, reveal that the formatting is consistent with what we would expect from contemporary newspaper issues, by and large. Each page consists of three columns of writing, with articles on generic news relevant to farmers and seasonal advice on specific farming practices comprising the majority of text. However, the newspapers interestingly include a decent amount of illustrations, as well as diagrams, data tables, and legal writing. These illustrations were clearly printed, since they are all flawless, black and white, and were produced at a time and place in which printing illustrations was common. The images and text were likely printed with a newspaper press using [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Relief_printing relief printing]. While Mid-Atlantic America at the time was seeing rapid innovations in printing technology, it wasn’t until the advent of the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rotary_printing_press rotary press] several decades after this volume’s creation that the industry was truly transformed. This text is also a case in point of how, similar to today, newspapers of the time found it in their best interest to squeeze as much information onto each page so as to minimize the costs of tangible inputs like paper and ink in proportion to the value they offer, which is information. | ||

Revision as of 00:33, 6 May 2022

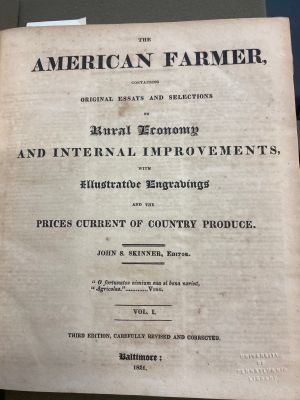

The American farmer : containing original essays and selections on rural economy and internal improvements, with illustrative engravings and the prices current of country produce Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; invalid names, e.g. too many, is a volume containing many newspaper issues pertaining to American agriculture which were released throughout the year of 1819. Published in 1821 in Baltimore, Maryland, the third edition of this text is currently maintained at the University of Pennsylvania’s Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts. There, it serves as a valuable resource for understanding both newspaper and agricultural industry in the early 19th century. Furthermore, it marks an episode in the long history of media in the United States in which newspapers, and specialized newspapers and magazines in particular, were on the rise [1].

Materiality, Printing, Publishing, and Distribution

The issues are bound using a dense type of cardboard, and the binding is covered with a fabric of tan and white string, with scattered brown stains across the front cover. The interior of each cover as well as the book’s first and last two pages are a unique, relatively thick type of paper that’s almost fully white but with small brown spots mixed in. The main pages are likely wood-pulp based, and are darker, very thin, more worn, and have lots of stains and ripples. The text can, in several places, be seen to bleed through to adjacent pages. It altogether consists of 416 pages, plus a title page and a seven-page annotated index titled ‘Contents of Vol. 1’, which includes terms deemed important to the volume’s editor, John S. Skinner.

The main title page, as well as the headings for each newspaper issue consist of various unique and interesting fonts. The book's headings and page numbers, for instance, reveal that the formatting is consistent with what we would expect from contemporary newspaper issues, by and large. Each page consists of three columns of writing, with articles on generic news relevant to farmers and seasonal advice on specific farming practices comprising the majority of text. However, the newspapers interestingly include a decent amount of illustrations, as well as diagrams, data tables, and legal writing. These illustrations were clearly printed, since they are all flawless, black and white, and were produced at a time and place in which printing illustrations was common. The images and text were likely printed with a newspaper press using relief printing. While Mid-Atlantic America at the time was seeing rapid innovations in printing technology, it wasn’t until the advent of the rotary press several decades after this volume’s creation that the industry was truly transformed. This text is also a case in point of how, similar to today, newspapers of the time found it in their best interest to squeeze as much information onto each page so as to minimize the costs of tangible inputs like paper and ink in proportion to the value they offer, which is information.

Marginalia and Provenance

The text contains little bits of scattered marginalia throughout, most of which are concise notes on the papers’ contents. These notes seem to indicate past scholarship in the field of agricultural journalism rather than practical notes from farmers. Interestingly, the handwritten quote “8 My 41 of Charles J. Biddle, Esq., To The Philadelphia Society for Promoting Agriculture” is included on the left margin of the first ‘contents’ page. However, originally this volume’s issues were printed by an individual named J. Robinson, and the volume altogether was likely bound together at a book-binding shop in Baltimore and given to the volume’s editor, John S. Skinner. It is known that the text was acquired by Charles J. Biddle sometime during the early to mid 20th century. Biddle was a prominent philadelphia lawyer, aviator, and author who would then donate the book to the Philadelphia Society for Promoting Agriculture. After all, these papers were likely bound together originally to serve as a new resource to help chronicle important aspects of agricultural history. Hence, the collection was ultimately donated to the Philadelphia Society for Promoting Agriculture and then to the University of Pennsylvania.

Role in the Agricultural and Newspaper Industries

American Farmer was a very popular and successful publication, and it was ultimately a product of the economy of agricultural newspapers at the time. Innovations in newspaper production technologies facilitated the creation of this text as did a growing demand for knowledge about how to farm effectively. Still, it was new innovations in printing and distribution that primarily facilitated the market and success of the American Farmer rather than a growing demand for knowledge related to efficient agricultural practices. This is evidenced by the fact that even as the United States saw tremendous growth in the agricultural sector as a result of technological innovation, mass immigration, and a rapidly growing populace, the newspaper industry of the early 19th century was expanding to an even greater extent [2]. Alongside the birth and growth of the ‘farm press’ [3]., in which The American Farmer was a major publication, citizens across the nation from increasingly diverse social, economic, ethnic, and geographic backgrounds began reading newspapers at a previously unseen level. Despite this trend, in the early 19th century many American farmers were still illiterate, and even those who weren’t were often dissuaded from basing their practices off of information from emerging newspaper and magazine publications due to a cultural taboo against ‘book farming’ [3] Innovations in printing, publishing, and news distribution further facilitated the profitability of collecting and organizing information on trends in the markets for agricultural products, and other data of interest to farmers, such as data on capital goods like emerging livestock breeds and crop cultivation methods.

Given this history, it is understandable that the issues of The American Farmer’s first volume contain such a broad set of content. The papers consist of information pertaining to a thoroughly diverse set of agricultural practices, and it is likely that farmers of all types of crops and livestock in existence in 1810’s America could find some useful information in the collection at large. The bulk of the papers’ content are articles offering advice pertaining to specific agricultural practices as well as news relevant to farmers as businessmen. In addition to these articles and the types of data tables previously mentioned, the papers’ contain images and diagrams intended to help farmers better understand their livestock’s health, agricultural equipment, and other important things for farmers.

Summary

This edition of The American Farmer offers many unique insights into the state of news journalism, agriculture, and their relation in the early 19th century. Thousands of American farmers of many different types of crops and livestock would have regularly purchased the individual issues of this volume [4], and primarily those farmers that knew Baltimore as their closest major metropolitan hub. While at the time, the phenomenon of agricultural journalism was in its youth and most farmers wouldn’t have typically read newspapers specifically tailored to them, many began to purchase them regularly along with common papers [4]. While this text reveals much about the history of agricultural journalism, it provokes further interesting questions. For instance, slavery is very rarely, if ever, mentioned in the volume even though it was published in early 19th century Maryland, which was home to many slaves.

References

- ↑ Boyce, George, et al. Newspaper history from the seventeenth century to the present day. Beverly Hills, Calif. : Sage Publications, 1978.

- ↑ Shaw, Matthew J. An Inky Business : A History of Newspapers from the English Civil Wars to the American Civil War. London: Reaktion Books, 2021.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Lurch, Donald G. Dissemination of farm information through newspapers, magazines, radio and television; a story of the services in the United States, including how they developed, function, and are financed. Washington: International Cooperation Administration, 1960.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Crawford, Nelson A. and Charles E. Rogers. Agricultural Journalism. Norwood, Mass. : The Plimpton Press, 1926.