Biblia Pauperum: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

===Paper and Print Quality=== | ===Paper and Print Quality=== | ||

The laid paper was made by hand in Holland using the same ancient method that would have been used to print the original version of Biblia Pauperum. The printers also incorporated deckle edges to create a rough and distressed look. The texture and color of the pages were made to precisely imitate those used in the fifteenth century. | The laid paper was made by hand in Holland using the same ancient method that would have been used to print the original version of Biblia Pauperum.<ref name="printing"> King, John N."'The Light of Printing': William Tyndale, John Foxe, John Day, and Early | ||

Modern Print Culture [*]." Renaissance Quarterly 54, no. 1 (2001): 52. Gale General OneFile </ref> The printers also incorporated deckle edges to create a rough and distressed look. The texture and color of the pages were made to precisely imitate those used in the fifteenth century. | |||

==Content== | ==Content== | ||

Revision as of 01:19, 3 May 2022

Introduction

At first glance, the laid paper and deckle edges of Biblia Pauperum seem to indicate that the book is from the fifteenth century. However, it is actually a facsimile created in 1884 that contains thirty-eight woodcut illustrations of scriptural events from the Bible along with supplemental text. This book is currently housed at University of Pennsylvania's Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, where is it catalogued as Biblia pauperum, containing thirty and eight woodcuts, illustrating the life, parables, and miracles of Our Blessed Lord & Savior Jesus Christ, with the proper descriptions thereof extracted from the original text of John Wycliffe...Preface by the late Very Rev. Arthur Penrhyn Stanley.

History

Original Woodblocks

A note by the printers, the Unwin Brothers of London, reveals that the original woodblocks were first displayed at the Caxton Celebration in 1877. During this celebration, an extraordinary collection of early printed books was exhibited at South Kensington. This made it one of the largest exhibitions of the printing industry in Europe of that time period. The exhibition was organized by large scale industrial printer William Clowes, typefounder and politician Sir Charles Reed, and printer and bibliographer William Blades, and other prominent individuals.

Approximately fifty years later in the early twentieth century, Mr. Sams of Darlington purchased the original blocks at Nuremberg. They were not recognized as belonging to any printed book and the artist’s mark, which appeared on the thirty-seventh plate, was unknown to any bibliographer. Therefore, it was probable that the woodblocks were unused for nearly four centuries after first being engraved.

Production of a Facsimile

When the printers acquired the original woodblocks, they saw that the woodblocks were remarkably clean and free from signs of wear, but extensively worm-eaten. In the case of one or two of the blocks, pieces of the surface were coming away in the hand. The soft wood was quite different from that used during the time period of the reprinting. Both the type of wood used and the unique manner in which the wood was cut were signs of their great antiquity.

This current copy of Biblia Pauperum contains the details of the original woodblocks, but reduced in size. It also includes supplemental text from Wycliffe’s translation of the New Testament, which was the only English version commonly known during the period when the woodblocks were originally engraved. The ornamented borders that are exact facsimiles of those from a Book of Hours which was printed by T. Kerver in Paris in 1525. With permission from the late Archbishop of Canterbury, the Unwin Brothers were able to reproduce the ornamentations of the Book of Hours stored in the Lambeth Palace Library.

Material Analysis

Overview

It is evident that that the printers went to extreme measures to imitate the original version of Biblia Pauperum, despite the fact that industrial printing was available during this time period. It seems that the printers went through all this extra work for the sake of scholarly documentation and artistic preservation of the sacred, religious work. This was a trend seen in the 19th century with the increasing number of facsimiles being created of ancient texts. This particular facsimile of Biblia Pauperum is notable because in addition to the scholarly and artistic significance, it is key to understanding how the Bible was taught in the Middle Ages, and specifically how the clergy taught the fundamentals of the Christian faith to ordinary people.

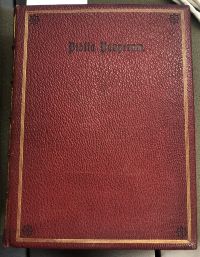

Cover, Binding, and Imposition

The cover of Biblia Pauperum seems to be made from red pebbled leather, which was often made by pressing small, regular bumps onto smooth calfskin. The cover is outlined by a series of gold lines and its four corners are decorated by small, simple flowers. The binding of the book is done in the style seen in the fifteenth century. Its design was taken from an early book in the British Museum. Upon opening the book, it can be observed that the endpapers are marbled with dark tones to produce elaborate patterns similar to smooth marble or other kinds of stone.

When the book is laid out flat, the pages seem to branch out from the center of the binding in a symmetrical manner. This can be justified by the observation of the shapes and sizes of the pages. Based on looking at the intermittent folio markings and overall imposition of the book, it seemed that the pages were formed by inserted plates and that there were four bifolia.

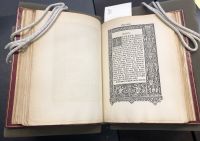

Title Page

The title page features the words Biblia Pauperum, Containing Thirty and Eight Woodcuts Illustrating the Life, Parables, and Miracles of Our Blessed Lord and Savior, Jesus Christ, With the Proper Descriptions Thereof Extracted from the Original Text of John Wycliffe, --- Rector of Lutterworth written in red and black-colored gothic script. It is interesting to note that the phrases, “Biblia Pauperum,” “Jesus Christ,” and “Arthur Penrhyn Stanley, D.D.” stand out on the page because of their red font. Two peculiar inconsistency were the presence of modern type to indicate the signature and the symbol of a paragraph mark at the bottom of the title page.

Paper and Print Quality

The laid paper was made by hand in Holland using the same ancient method that would have been used to print the original version of Biblia Pauperum.[1] The printers also incorporated deckle edges to create a rough and distressed look. The texture and color of the pages were made to precisely imitate those used in the fifteenth century.

Content

Prefatory Notice by the Late Very Rev. Arthur Penrhyn Stanley, D.D., Dean of Westminster

Arthur Penrhyn Stanley was an English Anglican priest and ecclesiastical historian. The Unwin brothers asked him to write a preface for reprinted version of Biblia Pauperum. Stanley wrote that the connection of Caxton’s press with the precincts of Westminster Abbey has often suggested the coincidence of the book and the church. He quoted Victor Hugo who claimed that “The Church has given birth to the Book.” Stanley observed that the woodblocks of Biblia Pauperum dated only seven years before the first appearance of Caxton’s first printed English book, making them a fitting memorial of the epoch by being commemorated by the Caxton Celebration. Biblia Pauperum was one of the last versions of the Bible that contained illustrations which were the main focus of the book. This differed from later, more common versions of the Bible that were printed and distributed in mass quantities.

Woodcut Illustrations

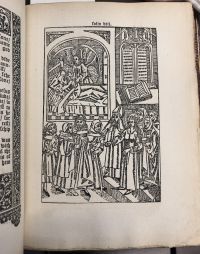

Unlike traditional illustrated Bibles in which the images are secondary to the text, Biblia Pauperum places the illustrations at the center of the book. Woodcuts are a relief printing technique in which an artist carves an image onto the surface of block of wood. This leaves the printing parts level with surface, while removing the non-printing parts of the wood. After ink is applied to the woodblock, the image at the surface carries the link to produce the final printed product. The use of the woodcut technique in producing the illustrations Biblia Pauperum results in distinct and rough strokes. Each illustration is in black-and-white ink.

One illustration (folio x) in the book displays two separate scenes. The bottom portion of the page features Mary and Joseph speaking to merchants in Bethlehem. The upper portion of the page shows the birth of Jesus in a manger surrounded by Mary and Joseph. Shepherds and angels can be seen outside the stable. This theme of including multiple scenes from the Bible on a single page is repeated throughout the book. Another illustration (folio xbiij) depicts the baptism of Jesus in the Jordan River by John the Baptist on the upper half of the page. The lower portion of the page shows a congregation of men (perhaps some of the disciples).

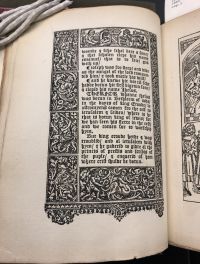

Text and Margins

Each woodcut illustration is preceded by two pages of text that accompanies the image. The text is written in Gothic script with forward slashes as its primary form of punctuation. There is a historiated initial at the beginning of the section that contains an intricately embellished first letter. Certain letters such as F or J are emphasized with exaggerated strokes. In addition, certain words have spellings that are different from the modern English language used today. For instance, generation is written as “generacioun” and Bethlehem is written as “Bethleem.” It is fascinating to note that the content of the text does not correspond to the illustrations surrounding it in the margins.

The margins are a facsimile of a Book of Hours from 1525, which is a Christian devotional book used to pray the canonical hours. These books were popular during the Middle Ages, so they are a common source of medieval illuminated manuscript. The margins of Biblia Pauperum are filled with drawings of Greek mythological creatures and abstract figures that contrast with the Christian text.

References

- ↑ King, John N."'The Light of Printing': William Tyndale, John Foxe, John Day, and Early Modern Print Culture [*]." Renaissance Quarterly 54, no. 1 (2001): 52. Gale General OneFile