John B. Thayer Titanic Memorial Collection: Difference between revisions

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

=== II. Thayer family material === | === II. Thayer family material === | ||

= | <div style="column-count:2"> | ||

Thayer, John B. (1862-1912), newspaper clippings and order of services at the Church of the Redeemer, paying tribute to, 1912 April 23-27, 1914 June 25. | * Folder 10: Thayer, John B. (1862-1912), newspaper clippings and order of services at the Church of the Redeemer, paying tribute to, 1912 April 23-27, 1914 June 25. | ||

* Folder 11: Thayer, John B. (1862-1912), photographic prints and biographical sketch, before 1912, 1999. | |||

Thayer, John B. (1862-1912), photographic prints and biographical sketch, before 1912, 1999. | * Folder 12: Thayer, John B. (1894-1945), photographic prints and biographical sketch, circa 1912-1917, 1999. | ||

* Folder 13: Thayer, Lois Cassatt (wife of John B. Thayer (1894-1945), letter from Robert Morris regarding Marian Longstreth Morris Thayer's death in 1944, 1974 August 13. | |||

Thayer, John B. (1894-1945), photographic prints and biographical sketch, circa 1912-1917, 1999. | * Folders 14-16: Thayer, Marian Longstreth Morris, letters from, photograph of, and silver-plated framed verse endorsed by Bruce Ismay, 1912-1913. | ||

* Folder 17: Thayer, Marian Longstreth Morris, photographic prints and biographical sketch, before 1912, 1999. | |||

Thayer, Lois Cassatt (wife of John B. Thayer (1894-1945), letter from Robert Morris regarding Marian Longstreth Morris Thayer's death in 1944, 1974 August 13. | </div> | ||

Thayer, Marian Longstreth Morris, letters from, photograph of, and silver-plated framed verse endorsed by Bruce Ismay, 1912-1913. | |||

Thayer, Marian Longstreth Morris, photographic prints and biographical sketch, before 1912, 1999. | |||

=== III. Efforts to memorialize the sinking of the Titanic === | === III. Efforts to memorialize the sinking of the Titanic === | ||

Revision as of 18:10, 2 May 2022

The John B. Thayer memorial collection of the Sinking of the Titanic is an archive of first-hand accounts, family material, and memorialization efforts kept by the prominent, Philadelphia-based Thayer family from 1912 to 2012. The collection was started in memory of John Borland Thayer II (Sr.) who died during the sinking of the ocean liner’s maiden voyage.

Thayer’s wife, Marian Longstreth Morris Thayer, and son, John “Jack” Borland Thayer III (Jr.), survived the tragedy and created the collection. As of 2014, the collection can be located at the University of Pennsylvania's Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts.

History

The Thayers were a prominent and wealthy family in the Philadelphia area at the turn of the 19th century. John Borland Thayer Sr. (1862-1912) was born in Philadelphia and attended the University of Pennsylvania. He was the Second Vice President of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company at the time of his death. He lived in Haverford, Pennsylvania with his wife, Marian Thayer, (1872-1944) and their four children: John “Jack” Borland Thayer Jr. (1894-1945), Frederick Morris Thayer (1896-1956), Margaret Thayer (1898-1960), and Pauline Thayer (1901-1981). In 1912, John, Marion, and Jack traveled to Europe and boarded the RMS Titanic for their return to the United States.

On the night of April 14, 1912, the Titanic disaster began. Separated from her husband and son by a large crowd, Marian boarded lifeboat 4. As the ship began to sink, 17-year-old Jack stood by the rail with passenger Milton Long, who he’d just met, said goodbye, and jumped feet first just before it split in half. He was pulled underwater by the suction of the sinking vessel, but found refuge on an overturned lifeboat and was eventually rescued by lifeboat 12. He was reunited with his mother on the RMS Carpathia. His father's body was never recovered. (John B. Thayer memorial collection of the Sinking of the Titanic, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, University of Pennsylvania, box 1, folder 3)

Four years later, Jack graduated from the University of Pennsylvania, served as a captain in the United States Army in World War I, and began his career in banking. He married Lois Buchanan Cassatt in 1917 and had six children: Edward and John (who both enlisted in the armed forces during World War II), Lois, Julie, Pauline, and Alexander, who died a few days after his birth. Jack served as treasurer and, later, financial vice-president for the University of Pennsylvania from 1939 until his death by suicide in 1945 at the age of 50. Contributions to the depression Jack suffered from later in life were the deaths of his son, Edward, and mother, Marian. A bomber pilot during the war, Edward’s plane was shot down in 1943 and his body was never found. Marion died at her home in Haverford on April 14, 1944, the 32nd anniversary of the Titanic disaster, at the age of 72.

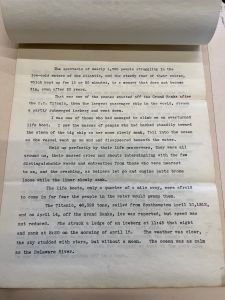

As a reader and researcher of the Thayer family’s history and memorial collection, I have adopted Astrid Rasch’s proposed strategy of anxious reading that subjects texts, specifically memoirs, to “critical scrutiny despite, and alongside, the empathy that we feel for our subjects…This entails acknowledging both the pain that the author has gone through and the traumatic experience of those represented, and at the same time examining the way in which that trauma is described and how it functions in the moral and political economy of the text in its context (Rasch 5). This subscription to anxious reading has allowed me to sympathetically engage with this memorial collection and the Thayer family who, as victims of a random and cruel trauma, have continued to bear witness to extreme suffering, grief, and loss since 1912. As Jack recalls in an article for the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin in 1932, "the spectacle of nearly 1,500 people struggling in the ice-cold waters of the Atlantic, and the steady roar of their voices, which kept up for 15 or 20 minutes, is a memory that does not become dim, even after 20 years" ("Sinking of Titanic," box 1, folder 4). Alongside this sympathetic reading is a critical examination of the Thayer family’s socioeconomic positions at the time of the sinking and beyond. As white Americans, aristocrats, and first-class survivors with ties to powerful institutions in the Philadelphia area, the Thayers had access to the technology, capital, and publishing resources that allowed for the creation, protection, and century-long maintenance of this extensive and historically valuable collection. Instead of ignoring the traumatic impact of the violence of the Titanic disaster on the Thayer family, I aim to follow Rasch and use this impact as a “point of departure that allows us to study not violence itself, but our own empathetic response to the traumatized victim, and to ask how such a response focuses our attention on some victims over others.” (Rasch 5) While focusing on the Thayers, I wish to keep in mind other victims and survivors who might not have had the socioeconomic means to maintain a memorial collection like the Thayers’, or whose voices have otherwise been drowned out by time and/or circumstance.

Content

I. First-hand accounts of the sinking of the Titanic

- Folder 1: Gracie, Archibald, letter to John Hagan regarding statements made by Hagan; also includes responses by Gracie clarifying events surrounding the sinking of Titanic (3 copies), 1912 September 26.

- Folder 2: Stephenson, Martha Eustis, and Elizabeth Mussey Eustis, "The Titanic: Our Story", undated.

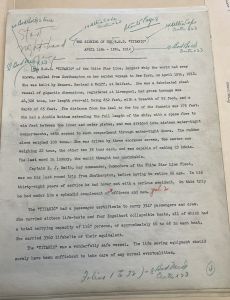

- Folder 3: Thayer, John B., account of the sinking dictated by Thayer and published in newspapers across the United States, 1912 April 21-26.

- Folders 4-5: Thayer, John B., "Sinking of Titanic," written for the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin (includes original ribbon typescript and published newspaper article), 1932.

- Folders 6-9: Thayer, John B., Sinking of the S.S. Titanic, (includes original carbon typescript, original ribbon typescript, galley proofs [1 clean and 1 corrected copy], and Library of Congress certificate of copyright registration), 1940.

This seems relevant to the collection to support the idea that Thayer’s initial testimony and published memoir are probably accurate retellings of what actually happened the night of the shipwreck and reliable accounts of history. [1]

II. Thayer family material

- Folder 10: Thayer, John B. (1862-1912), newspaper clippings and order of services at the Church of the Redeemer, paying tribute to, 1912 April 23-27, 1914 June 25.

- Folder 11: Thayer, John B. (1862-1912), photographic prints and biographical sketch, before 1912, 1999.

- Folder 12: Thayer, John B. (1894-1945), photographic prints and biographical sketch, circa 1912-1917, 1999.

- Folder 13: Thayer, Lois Cassatt (wife of John B. Thayer (1894-1945), letter from Robert Morris regarding Marian Longstreth Morris Thayer's death in 1944, 1974 August 13.

- Folders 14-16: Thayer, Marian Longstreth Morris, letters from, photograph of, and silver-plated framed verse endorsed by Bruce Ismay, 1912-1913.

- Folder 17: Thayer, Marian Longstreth Morris, photographic prints and biographical sketch, before 1912, 1999.

III. Efforts to memorialize the sinking of the Titanic

Folder 18

Academy Chicago Publishers, correspondence with Richard Fremont-Smith and Pauline Thayer Maguire regarding re-publishing The Sinking of the S.S. Titanic, by John B. Thayer, 1997-2006.

Folder 19

Baldwin, Hanson, story entitled, "R.M.S. Titanic," possibly published in Harpers Monthly Magazine, 1932.

Folder 20

Lists of and articles about artifacts, books, and collections relating to Titanic, 1985-2012.

Folder 21

Lord, Walter, letters to Robert Maguire regarding Life Boat 1, 1983 July-September.

Folder 22

Maguire, Pauline Thayer, letters to Vermont senators and representatives regarding the "RMS Titanic Maritime Memorial Preservation Act of 2006", 2007 April 14.

Folder 23

Newspaper clippings regarding the sinking of Titanic and its aftermath, 1912 April 16-17, June 1.

Folder 24

Newspaper clippings regarding and obituaries for Titanic survivors, 1996-2007, undated.

Folder 25

Thornwillow Press, letters from Luke Ives Pontifell to Robert Maguire regarding special limited edition of The Sinking of the S.S. Titanic, by John B. Thayer, 2012.

Folder 25

Wallace, Merie Weismiller, letters to Robert and Pauline Maguire regarding James Cameron's film, Titanic, 1996.

Folder 26

Wilson, Frances, correspondence to Robert Maguire regarding Wilson's writings on Titanic and Bruce Ismay, 2012.

Notable Items

Newspaper Scrapbook of Jack Thayer's Testimony

They news clippings have been cut out and pasted to sheets of manila paper and were probably bound together in a binder, as evidenced from a hole punched on the left side of each sheet of paper. from over 57 newspapers nationwide. The first of Mussell’s arguments is that surviving ephemera are an essential and uncanny part of cultural memory. As symbols of everyday, mundane life printed ephemera ``stand for the complexity of the quotidian and their persistence belies the selective acts of memory through which we narrate our relation to the past” [2] Mussell also discusses the industrialization of print in the Victorian era and examines how newspapers at once acted as informational media and objects of record. I think these arguments could be applied to this memorial collection given that it begins with Thayer’s large collection of news clippings documenting his initial survivor’s testimony and other important events as they occurred after the shipwreck like the construction of memorials, the display of recovered artifacts and survivors’ deaths. The Thayer family’s careful curation and deliberate preservation of these specific clippings relay the type of history that they—as victims of tragedy—selected to remember and record. Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; invalid names, e.g. too many

-

Columbus Dispatch - April 21, 1912

-

New York City World - April 21, 1912

-

Baltimore Sun - April 21, 1912

-

Davenport Democrat & Sioux City Journal - April 21-24, 1912

-

Titusville Herald - April 24, 1912

-

Memphis Commercial Appeal & Nashville Tennessean - April 21, 1912

-

Washington Post - April 21, 1912

-

New York City Tribune - April 21, 1912

-

Newark Sunday Call - April 21, 1912

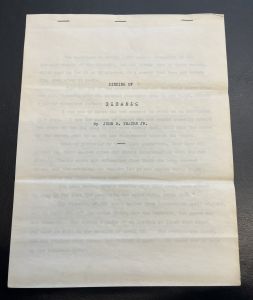

The Sinking of the S.S. Titanic, April 14-15, 1912

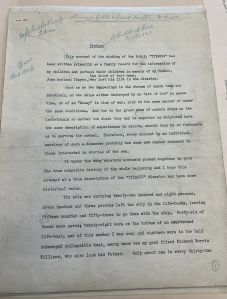

Rasch argues for a method of anxious reading of trauma memoirs that dares to “subject texts to critical scrutiny despite, and alongside, the empathy that we feel for our subjects…This entails acknowledging both the pain that the author has gone through and the traumatic experience of those represented, and at the same time examining the way in which that trauma is described and how it functions in the moral and political economy of the text in its context." [3] (5). I believe this is relevant to the Thayer collection, and especially his memoir, in that it encourages a critical examination of Thayer, as a wealthy, white, first-class survivor and historical authority of the Titanic tragedy. How likely is it that the few impoverished immigrants who survived the wreck were able to manage a collection as vast as Thayer’s or had access to the technology, capital, or publishing resources that aided in the creation (and copyright protection) of Thayer’s memoir?

-

Original ribbon typescript with proofreader's corrections

-

Preface with proofreader's corrections

-

Title page

-

First page

Letter regarding James Cameron's Titanic

and manifests more official and authoritative efforts to memorialize the tragedy, including Jack’s privately published memoir, the public re-publishing of the same memoir by his cousin, and documentation of James Cameron’s efforts to authenticate his film by consulting Thayer family records. Some of my photos of the collection are linked here. Middleton and Woods argue that contemporary popular culture imagines the past as a traumatic memory to which access can be gained through a technics of memory and representation which will reveal it as a witnessable location in time and space. They effectively do so by examining the James Cameron’s 1997 film Titanic and Walter Lord’s 1995 book A Night to Remember and their reliance on the Titanic archive—including first-hand accounts (like Thayer’s), footage and recovered artifacts of the wreck—to produce commodified spectacles of history that redeems the past in the present and shapes contemporary social memory of the tragedy. Besides featuring the influence of Thayer’s memoir on Lord’s book, I think this article is relevant to the collection because its ideas on the progression of historical representations of tragedy mirror the representations of the past seen in the collection from 1912-2014. [4]

Legacy

References

- ↑ Riniolo, T. C., Koledin, M., Drakulic, G. M., & Payne, R. A. An archival study of eyewitness memory of the titanic's final plunge. The Journal of General Psychology, 130(1), 2003. 89-95. Retrieved from https://proxy.library.upenn.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/archival-study-eyewitness-memory-titanics-final/docview/213652240/se-2?accountid=14707

- ↑ Mussell, James. "THE PASSING OF PRINT: Digitising Ephemera and the Ephemerality of the Digital." Media History, vol. 18, no. 1, 2012. pp. 77-92.

- ↑ Rasch, Astrid. "Anxious Reading: Interrogating Selective Empathy in Trauma Memoirs." Auto/biography Studies, 2021, pp. 1-26.

- ↑ Peter Middleton & Tim Woods. “Textual memory: The making of the Titanic's literary archive.” Textual Practice, 15:3, 2001, 507-526. DOI: 10.1080/09502360110070420