Catharine Gould Scrapbook: Difference between revisions

| Line 22: | Line 22: | ||

=="Books of Scraps"== | =="Books of Scraps"== | ||

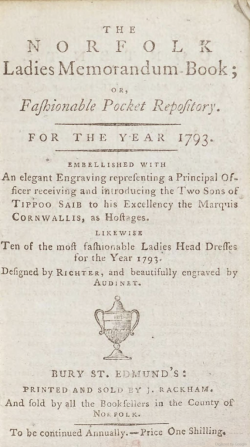

[[File:CGSNorfolk.png|thumb| | [[File:CGSNorfolk.png|thumb|250px|left|The Norfolk Ladies Memorandum Book; Or, Fashionable Pocket Repository For the Year 1793]] | ||

Beside the unique handiworks in the scrapbook, most pages of the scrapbooks are filled with poems that are foreign to the modern readers. These are not the famous poems that we know from Georgian England; rather, we find an electric mix of charades, enigmas, epigrams, and hymns excerpted from popular, ephemeral publications, few of which are documented in digital repositories. Out of the 100+ poems I studied, I was able to find two publications that match up with clippings in terms of their content, layout, and typeface: [https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_London_Magazine_Or_Gentleman_s_Month/FSkoAAAAYAAJ?hl=en Volume 21 of The London Magazine, Or, Gentleman's Monthly Intelligencer], and [https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Norfolk_Ladies_Memorandum_Book_Or_Fa/Z0QV0b394pYC?hl=en The Norfolk Ladies Memorandum Book; Or, Fashionable Pocket Repository For the Year 1793]. | Beside the unique handiworks in the scrapbook, most pages of the scrapbooks are filled with poems that are foreign to the modern readers. These are not the famous poems that we know from Georgian England; rather, we find an electric mix of charades, enigmas, epigrams, and hymns excerpted from popular, ephemeral publications, few of which are documented in digital repositories. Out of the 100+ poems I studied, I was able to find two publications that match up with clippings in terms of their content, layout, and typeface: [https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_London_Magazine_Or_Gentleman_s_Month/FSkoAAAAYAAJ?hl=en Volume 21 of The London Magazine, Or, Gentleman's Monthly Intelligencer], and [https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Norfolk_Ladies_Memorandum_Book_Or_Fa/Z0QV0b394pYC?hl=en The Norfolk Ladies Memorandum Book; Or, Fashionable Pocket Repository For the Year 1793]. | ||

Revision as of 16:43, 26 April 2022

Introduction

Tucked away in the corners of archives and special collection libraries are a number of old, handmade books that have baffled historians for decades.[1] These books are often hidden under the guise of many names: scrapbooks, albums, commonplace books, blank books. Because these books were never published or circulated in the public sphere, they do not follow the rules and conventions that govern other printed books, providing little information about their production and making it difficult to catalog and understand. At the same time, because of their idiosyncratic nature, these books provide readers with a fascinating glimpse into the inner lives of their makers, offering a snapshot of reading practices at the time of their making.

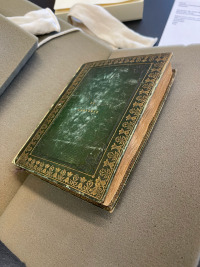

One such book is Ms. Codex 1860, otherwise known as the Catharine Gould scrapbook, in the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts at the University of Pennsylvania. Less than one inch thick, the book is case-bound in lavish green leather and adorned with gold engravings and edges. Inside we find clipped and pasted published poems and images along with a number of handiworks, including handwritten notes, hand drawings and paintings, feathers, pressed flowers and leaves, and locks of hair. Though unusual to modern readers, these items are quite popular and are found in other well-documented historical scrapbooks like Elizabeth Reynolds's A Medley, Anne Wagner's Memorials of Friendship, and the Elizabeth Reynolds scrapbook.[1]

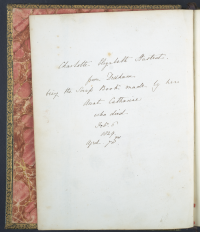

Penn Libraries purchased the book at a 2017 auction at Cheffins, in Cambridge, United Kingdom with the assistance from the Zachs-Adams Rare Book Fund, and it has since remained in the stacks.[2] The long history of how the book ended up at the auction remains somewhat shrouded in mystery, but we could trace its provenance to the woman named Catharine Gould, who lived in Essex County in England. There are no traces of her presence online aside from a will in which she bequeathed her manuscript books to her niece.[3] Indeed, the first page of the scrapbook reads, "Charlotte Elizabeth Hasted from Dedham being the scrapbook made by her Aunt Catharine who died Feb. 6, 1829, aged 78 yrs.”

This note provides us with abundant information to begin our investigation of the book. It not only identifies it as a scrapbook, but situatuates us in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth century in Northeast England. Drawing from this information, let us now delve deeper to explore the scrapbook and its personal, cultural, and historical significance.

History of the Genre

It is difficult to place handmade books into genres because each book is different and the categories are changing as we speak. But because the writing on the front page identifies the book as a scrapbook, we might first consider it in light of the scrapbook genre. The Oxford English Dictionary records the first use of the term “scrapbook” in 1825, though it has been used in other private documents like the 1817 Elizabeth Reynolds scrapbook, which contains similar materials like feathers and watercolor paintings as the Catharine Gould scrapbook.[4] The general consensus today is that the term scrapbook refers to books whose contents have been cut and pasted in from other sources.[1]

While the term scrapbook is new to the seventeenth century, the notion of cutting and pasting is not. In fact, the practice is common in the manuscript culture of the commonplace books. Commonplace books are books where the creators write down notable passages from other works and organize them under different categories.[5] We could trace the practice of collecting and reproducing handwritten passages to Cicero and Quintilianus, who encouraged students to write on an album, the latin word for “white” that would come to refer to a blank tablet and later a blank book.[6]

Even though both commonplace books and scrapbooks involve filling a blank book with materials found elsewhere, there is an important distinction: the scrapbook is composed of printed materials. In this respect, scrapbooks are described as an “industrialized and democratized” form of the commonplace books.[5] As print becomes cheaper, even people who could not write are able to preserve a larger quantity of material at a much faster pace. At the same time, it also led people to omit information about the source and arrange them in a more manner that became characteristic of most scrapbooks as we know it.[5]

"Books of Scraps"

Beside the unique handiworks in the scrapbook, most pages of the scrapbooks are filled with poems that are foreign to the modern readers. These are not the famous poems that we know from Georgian England; rather, we find an electric mix of charades, enigmas, epigrams, and hymns excerpted from popular, ephemeral publications, few of which are documented in digital repositories. Out of the 100+ poems I studied, I was able to find two publications that match up with clippings in terms of their content, layout, and typeface: Volume 21 of The London Magazine, Or, Gentleman's Monthly Intelligencer, and The Norfolk Ladies Memorandum Book; Or, Fashionable Pocket Repository For the Year 1793.

This is the norm and not the exception for scrapbooks in this period. In fact, Garvey writes that in all the scrapbooks she studied, “all the classics from the eighteenth century were absent.” Rather, we find items from the “cheaper popular circulation” that are different from “the more centralized power of prestigious book and magazine publication."[5] As the practice of scrapbooking became popular, some books were sold as “book of scraps” with the expectation that their purchaser would scissor them out and paste them into a scrapbook of her own.[7] Scrapbooks offer the readers a fascinating glimpse to the other side of popular reading culture that we never knew about, production of poems that were meant as decoration rather than consumption.

Because these books are ephemeral and sometimes meant to be cut, they are often produced with a low budget. The poems are printed with a stereotype caste on a thin paper so that the texts are visible on the other side, some texts sometimes faded. The papers are also tinted with a blue color, which is reminiscent of the blue books we find for record keeping and other utilitarian purposes dating back to 15th century England. Yet even though these books cost much less than a regular book, such books were still expensive for most people.[8] Therefore, most women who create scrapbooks come from upper-middle class, and we might speculate the same for Catharine Gould.

Use & Rearrangement

Readership & Circulation

Authorship & Copyright

Impact & Significance

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Deidre Lynch, "Paper Slips: Album, Archiving, Accident," Studies in Romanticism 57, no. 1 (2018): https://proxy.library.upenn.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/paper-slips-album-archiving-accident/docview/2061875748/se-2?accountid=14707.

- ↑ "Catharine Gould Scrapbook," Philadelphia Area Archives Research Portal, http://dla.library.upenn.edu/dla/pacscl/detail.html?id=PACSCL_UPENN_RBML_PUSpMsCodex1890.

- ↑ "Will of Catharine Gould, Spinster of Dedham, Essex," The National Archive, https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/D259435.

- ↑ "Scrapbook," Oxford English Dictionary, https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/173320?rskey=2ApOj1&result=1&isAdvanced=false#eid.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Ellen Gruber Garvey, Writing with Scissors (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), https://oxford-universitypressscholarship-com.proxy.library.upenn.edu/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195390346.001.0001/acprof-9780195390346.

- ↑ Susan Tucker, Katherine Ott, and Patricia Buckler, "An Introduction to the History of Scrapbooks," introduction to The Scrapbook In American Life (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2006).

- ↑ Deidre Lynch, "Wedded to Books: Nineteenth Century Bookmen at Home," in Loving Literature: A Cultural History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), https://doi-org.proxy.library.upenn.edu/10.7208/9780226183848.

- ↑ Stephen Colclough, Consuming Texts: Readers and Reading Communities, 1695-1870 (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007).