The timber-tree improved, or, The best practical methods of improving different lands, with proper timber...: Difference between revisions

| (5 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

===Content=== | ===Content=== | ||

[[File:SamplePageEL.jpg|thumb|200px|Sample page. Note the headings and page numbers.]] | [[File:SamplePageEL.jpg|thumb|200px|Sample page. Note the headings and page numbers.]] | ||

The content of the book is divided into chapters and subchapters. Each chapter is about a different type of tree, such as the pear tree, oak tree, or ash tree, and begins with descriptions and common uses of each tree. Following these introductions, subchapters are used to describe a number of different methods to improve the health of each tree and the quality of its timber. Some chapters have up to eight subchapters describing these methods. | The content of the book is divided into chapters and subchapters. Each chapter is about a different type of tree, such as the pear tree, oak tree, or ash tree, and begins with descriptions and common uses of each tree. Following these introductions, subchapters are used to describe a number of different methods to improve the health of each tree and the quality of its timber. Some chapters have up to eight subchapters describing these methods. One such method Ellis describes to improve growth conditions for the oak tree is to sow half of the acorn crop on the surface and the other half much deeper into the ground, which in Ellis' experience mimics nature as much as possible and also enables some of the crop to be protected from birds or rodents. Afterwards, he also remarks about cases in which the method wouldn't work and the conditions of the soil that would make this method work the best. | ||

Each page includes a heading that denotes the chapter the reader is reading as well as a page number. Some pages also have a number and letter at the bottom to indicate how the pages should be folded by the publisher after printing. | Each page includes a heading that denotes the chapter the reader is reading as well as a page number. Some pages also have a number and letter at the bottom to indicate how the pages should be folded by the publisher after printing. | ||

| Line 44: | Line 44: | ||

===Platform, Structure, and Binding=== | ===Platform, Structure, and Binding=== | ||

The covers and spine of this book contain [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pulp_(paper)#Wood_pulp wood pulp] wrapped in some sort of leather material. The front cover of the book has detached from the rest of the book, likely due to age. The leather material the cover is wrapped in is also deteriorating and flaking off due to age. The book seems to be presented in a very standard platform, with a vertical rectangular shape, binding with cloth thread, and a cover made with wood material similar to cardboard wrapped in animal skin. | The covers and spine of this book contain layers of [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pulp_(paper)#Wood_pulp wood pulp] wrapped in some sort of leather material. The front cover of the book has detached from the rest of the book, likely due to age. The leather material the cover is wrapped in is also deteriorating and flaking off due to age. The book seems to be presented in a very standard platform, with a vertical rectangular shape, binding with cloth thread, and a cover made with wood material similar to cardboard wrapped in animal skin. | ||

The book is bound with some sort of threaded material or string in a way that is contemporary with the publication date, which can be seen especially because this copy’s front cover is detached. | The book is bound with some sort of threaded material or string in a way that is contemporary with the publication date, which can be seen especially because this copy’s front cover is detached. | ||

| Line 63: | Line 63: | ||

===Specific Copy=== | ===Specific Copy=== | ||

[[File:SecondPartTitleEL.jpg|thumb|200px|Title of the second part. At left is the back of the page used for the publisher's advertisement.]] | [[File:SecondPartTitleEL.jpg|thumb|200px|Title of the second part. At left is the back of the page used for the publisher's advertisement.]] | ||

The first and second parts of the book were written and published in separate years. The first part of the book was published in 1744 by T. Osborne and M. Cooper. It is the third edition of the first part, with the original edition possibly being printed in 1741. The second part also lists T. Bacon as a publisher and was published in 1742. Because the book was published in two separate parts, the compilation of this copy, which puts together both parts into one bound book, must have been done at some point after the third edition of the first part was published in 1744. Additionally, at the end of the first part, it seems there is also advertising for J. and J. Fox, a different publisher, who may have selectively published the first part. This suggests that the book was published by several different people and their businesses, and that some of the publishers may have changed between the two parts or after the two parts | The first and second parts of the book were written and published in separate years. The first part of the book was published in 1744 by T. Osborne and M. Cooper. It is the third edition of the first part, with the original edition possibly being printed in 1741. The second part also lists T. Bacon as a publisher and was published in 1742. Because the book was published in two separate parts, the compilation of this copy, which puts together both parts into one bound book, must have been done at some point after the third edition of the first part was published in 1744. Additionally, at the end of the first part, it seems there is also advertising for J. and J. Fox, a different publisher, who may have selectively published the first part. This suggests that the book was published by several different people and their businesses, and that some of the publishers may have changed between the two parts or after the two parts started being bound together into a singular book. | ||

===Format and Navigation=== | ===Format and Navigation=== | ||

| Line 86: | Line 86: | ||

==Significance== | ==Significance== | ||

[[File:ShipEL.jpg|thumb|300px|[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HMS_Royal_George_%281756%29 HMS ''Royal George''], a ship of the line that would have been made from timber and launched in 1756. Painted by [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Cleveley_the_Elder John Cleveley the Elder] in 1757.]] | |||

In the mid-1700s, a time of substantial agricultural advancements and increasing industrialization, timber as a resource was a vital resource in England. Ways to improve land and tree crops to produce high quality timber, which are described in this book, were most likely contributed in part to the success of Britain as a growing industrial power into the 1800s. One reason was that high quality timber was a precious commodity used in building ships. At the time, with the Royal Navy being one of the most powerful naval forces in the world and vying with the navies of other countries like the Netherlands and France for maritime supremacy, timber would have been used to produce ships for the navy as well as trading vessels. By spreading knowledge about the properties of a variety of different types of wood, this book would have played a part in the success of the Royal Navy into the 1800s before the advent of iron and steel ships. | In the mid-1700s, a time of substantial agricultural advancements and increasing industrialization, timber as a resource was a vital resource in England. Ways to improve land and tree crops to produce high quality timber, which are described in this book, were most likely contributed in part to the success of Britain as a growing industrial power into the 1800s. One reason was that high quality timber was a precious commodity used in building ships. At the time, with the Royal Navy being one of the most powerful naval forces in the world and vying with the navies of other countries like the Netherlands and France for maritime supremacy, timber would have been used to produce ships for the navy as well as trading vessels. By spreading knowledge about the properties of a variety of different types of wood, this book would have played a part in the success of the Royal Navy into the 1800s before the advent of iron and steel ships. | ||

Latest revision as of 08:33, 13 May 2024

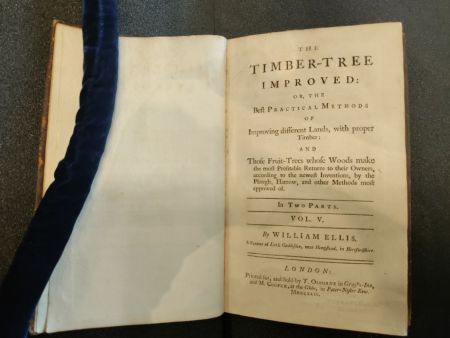

The timber-tree improved, or, The best practical methods of improving different lands, with proper timber: and those fruit-trees whose woods make the most profitable returns to their owners, according to the newest inventions, by the plough, harrow, and other methods most approved of: in two parts was authored by William Ellis in two separate parts around 1744-1745. Much like its title suggests, the book suggests ways to improve the health of timber and fruit trees as well as the quality of timber obtained from such trees.[1]

Background

Historical Context

The British Agricultural Revolution, commonly referred to as the Second Agricultural Revolution, was a time period of increased agricultural productivity approximately between 1550 and 1880. A slew of new technologies and structural innovations such as new field rotation systems, greater use of fertilizers, and selective breeding of livestock enabled huge advances in the field of agriculture, especially within England.[2] With population growth and increasing urbanization, advancements in agriculture were highly important in keeping food available and prices low. New crops, including new types of trees from around the world, were grown in England throughout the year, and increasing numbers of laborers and more intensive labor were required by these new crops and technologies.[3] In Britain, the limited amount of resources confined to the island, specifically in timber, was a constraining factor on the agricultural and industrial revolutions occurring in Britain around the time, and while coal began to be produced in the 1700s as a new fuel source, timber was still widely used for fuel, construction, and other materials. Very low forest cover across England meant that timber needed to be harvested from tree crops.[4]

In this context, the use of timber as an important resource in the 1700s made it very important for landowners and farmers to plant trees and harvest timber on their own land. This book, which suggests a variety of ways farmers can improve their own tree crops and harvest higher quality timber, would have been very useful at the time for farmers in England. Demand for different types of wood would have made them desired commodities, and this book gives suggestions on how timber could be improved so that farmers might be able to sell it later for better prices. In addition, because this book discusses so many different trees, it was useful in the American colonies and continental Europe as well, where the Industrial and Second Agricultural Revolutions were also spreading to and the knowledge could be used in a similar fashion.[5]

Author

The book was written by William Ellis, who claims in the preface that he wrote this book because he wants to share certain methods and secrets related to forestry and trees with other farmers and timber harvesters. Ellis was important to the agricultural history of England and at the time was the most widely published author of agricultural books in England in what can be called agricultural journalism. Ellis also wrote other books related to agriculture as well, which was based on not only his own experiences in farming but also conversations he held with others he met while traveling. His books were very widely read throughout Europe and the American colonies, and he took these opportunities to advertise his own business as an agricultural supplier.[5] William Ellis was born approximately in 1700 and died in 1759.

Circulation and Audience

William Ellis authored the book from his farm in Little Gaddesden in Hertfordshire, and the book was printed and published in London. Text denoting the publishers' names and locations suggests that it was published and distributed in England and Ireland. Other texts and evidence suggest that the book was also read throughout continental Europe and in the American colonies.[5]

Because of the Statute of Anne in 1710, the object is most likely copyrighted to the William Ellis and licensed to specific printers that are listed within the book. The fact that the author’s name is clearly listed on the title page in relatively large font suggests that credit and possible copyright is being given to the author. The publisher’s names at the bottom of the title page and advertisements at the end of each part suggest that the content of the book is being licensed to the publishers by Ellis, who wants to make it clear who wrote the book, as the book also serves as an advertisement for his own farmstead and business.

The book was most likely read by farmers and timber harvesters who wanted to enter the business of growing trees and harvesting timber or were looking to make their farms healthier and more capable of producing good timber. In addition, some sections of the book also relate to the health of fruit trees, which may also be useful to farmers with orchards. The layout and content of the book suggest that the book was not made in mind for casual reading but for referencing specific sections when the time came. Most likely, farmers who wanted to expand the variety of trees their farm was growing would reference the specific chapters of the book related to the trees that they wanted to grow. Other farmers who had trees that were sickly and not growing well could reference the sections of the book about the trees they were growing and potentially find methods to improve the trees' health.

Provenance

This copy of the book was owned by Lord Edward Suffield. This is apparent from the bookplate within the front cover, which matches up with Edward the 3rd Baron of Suffield's coat of arms. There is no clear date that notes when Penn acquired the book, so it is reasonable to say that it was acquired sometime during or after Lord Edward Suffield's lifetime from 1781 to 1835. The lack of any markings that may have been made by other owners or readers of the book also suggest that the book was acquired during or shortly after Lord Suffield passed.

-

Lord Edward Suffield

-

Bookplate located on the inside of the front cover.

Content

The content of the book is divided into chapters and subchapters. Each chapter is about a different type of tree, such as the pear tree, oak tree, or ash tree, and begins with descriptions and common uses of each tree. Following these introductions, subchapters are used to describe a number of different methods to improve the health of each tree and the quality of its timber. Some chapters have up to eight subchapters describing these methods. One such method Ellis describes to improve growth conditions for the oak tree is to sow half of the acorn crop on the surface and the other half much deeper into the ground, which in Ellis' experience mimics nature as much as possible and also enables some of the crop to be protected from birds or rodents. Afterwards, he also remarks about cases in which the method wouldn't work and the conditions of the soil that would make this method work the best.

Each page includes a heading that denotes the chapter the reader is reading as well as a page number. Some pages also have a number and letter at the bottom to indicate how the pages should be folded by the publisher after printing.

While illustrations might be expected for each tree, there are no illustrations within the book. This could have been because of the high cost of hiring an illustrator for the book, especially because the pages would have to be sent to the illustrator after being printed and before being bound.

Physical Attributes

Platform, Structure, and Binding

The covers and spine of this book contain layers of wood pulp wrapped in some sort of leather material. The front cover of the book has detached from the rest of the book, likely due to age. The leather material the cover is wrapped in is also deteriorating and flaking off due to age. The book seems to be presented in a very standard platform, with a vertical rectangular shape, binding with cloth thread, and a cover made with wood material similar to cardboard wrapped in animal skin.

The book is bound with some sort of threaded material or string in a way that is contemporary with the publication date, which can be seen especially because this copy’s front cover is detached.

-

Front cover

-

Front cover detached

Substrate

The book's substrate is made primarily from wood pulp, similar to materials found in other books made around the same time period this book was published. Within the book, the pages have consistent horizontal lines, suggesting that the paper was most likely printed within a paper mill. The pages also have a consistent reddish-yellowish hue, which is most likely due to the natural aging of the book.

Marginalia

This copy of the book does not appear to have any markings in its pages, excluding the bookplate from the original owner and markings made by the library for cataloging purposes. This may suggest that the book was not heavily read before the book entered circulation within Penn Libraries, or that Lord Suffield or subsequent book owners were very careful not to leave behind any markings or marginalia within the book. The book also has no evidence of any stains or discolorations within its pages, further suggesting that it was not read a substantial amount before being donated to Penn Libraries, or that whoever did read it made sure that they were not leaving any markings within the book.

Specific Copy

The first and second parts of the book were written and published in separate years. The first part of the book was published in 1744 by T. Osborne and M. Cooper. It is the third edition of the first part, with the original edition possibly being printed in 1741. The second part also lists T. Bacon as a publisher and was published in 1742. Because the book was published in two separate parts, the compilation of this copy, which puts together both parts into one bound book, must have been done at some point after the third edition of the first part was published in 1744. Additionally, at the end of the first part, it seems there is also advertising for J. and J. Fox, a different publisher, who may have selectively published the first part. This suggests that the book was published by several different people and their businesses, and that some of the publishers may have changed between the two parts or after the two parts started being bound together into a singular book.

This book is a codex and exists in a quarto format, which is evidenced by the fact that pages are in groupings of 8. The publisher page numbering used to denote the quarto format is very standard. A letter and number printed at the bottom of each page (i.e. B2) were used by the publisher to compile the book properly in the right page order.

The book provides a table of contents for both the first and second parts. There are page numberings throughout the book, one set for the first part and another set for the second part. Each page has a heading at the top that indicates the section or chapter of the book the page is located within. Each chapter has a very clear beginning, which is evidenced by a printed line of flower illustrations and larger text with the title of the new section. These mechanisms may indicate that readers might be expected to have to reference only specific sections of the book at certain times, since the book is clearly delineated by headings, subheadings, and page numbers. However, a certain level of reading skill and book familiarity is also expected from readers, since they are expected to have knowledge of how to use these mechanisms to their advantage.

-

First page of first part's Table of Contents at right. Second page of Preface at left.

-

First page of second part's Table of Contents at right. Advertisement for another book written by William Ellis at left.

-

Beginning of new chapter at left denoted by flower illustrations and chapter title. Note the front page of the publisher's advertisement at right.

Other Attributes

The author includes a preface at the beginning of the first part. This preface uses a first person perspective and describes why the book was written, suggesting that the preface was written by the author himself. The preface includes information on why Ellis is qualified to write the book and what benefits the book can give the reader.

The book also includes two publishers' advertisements, one after the first part and the other after the second part. Both advertisements are from different publishers and use both a front and back page to list the books being published by the specific publishers, encouraging readers to buy these other books as well. This was most likely a result of the publisher having an extra page to print on and using it to advertise the books they were selling.

The second part of the book also includes an advertisement for another book William Ellis was in the process of writing on the back of the second part's title page. This book was entitled The Modern Husbandman, For the Month of June.

Significance

In the mid-1700s, a time of substantial agricultural advancements and increasing industrialization, timber as a resource was a vital resource in England. Ways to improve land and tree crops to produce high quality timber, which are described in this book, were most likely contributed in part to the success of Britain as a growing industrial power into the 1800s. One reason was that high quality timber was a precious commodity used in building ships. At the time, with the Royal Navy being one of the most powerful naval forces in the world and vying with the navies of other countries like the Netherlands and France for maritime supremacy, timber would have been used to produce ships for the navy as well as trading vessels. By spreading knowledge about the properties of a variety of different types of wood, this book would have played a part in the success of the Royal Navy into the 1800s before the advent of iron and steel ships.

Increasing urbanization and construction saw additional uses for sturdy timber. With low forest cover across England, timber needed to be farmed and harvested for use in both building structures and internal furnishings. Healthy timber was necessary to construct high quality furniture and materials for housing, which would have sold for higher prices.

Timber was also used as an important source of fuel. In the early and mid-1700s, coal was not widely exploited, since the Industrial Revolution had not begun yet in full force. Timber remained a widely used source of fuel in furnaces, stoves, and eventually steam engines once they were developed. Enabling timber to grow as fast and strong as possible, which this book described in detail, would have enabled the production of a good fuel source in England at a time when non-farmed wood was a scarce commodity.

Finally, British dependence on imported wood from the Baltic region for certain types of wood, especially those good for shipbuilding, meant that producing domestic timber and relying less on timber obtained from trade agreements would have helped England's economy and its navy to some degree.[6] Since this book would have enabled many different farmers to plant tree crops and produce healthy timber, it may have made a significant difference in reducing Britain's dependence on timber imports.

Overall, The timber-tree improved, or, The best practical methods of improving different lands, with proper timber: and those fruit-trees whose woods make the most profitable returns to their owners, according to the newest inventions, by the plough, harrow, and other methods most approved of: in two parts is a book that most likely had an impact on timber production, especially in England, and associated activities, including shipbuilding, construction, and fuel production. While written by a relatively unknown farmer from Hertfordshire, his book spread across Europe and the American Colonies and may have impacted timber production and practices far beyond what he had envisioned when he penned the book.

References

- ↑ W. Ellis, The timber-tree improved, or, The best practical methods of improving different lands, with proper timber : and those fruit-trees whose woods make the most profitable returns to their owners, according to the newest inventions, by the plough, harrow, and other methods most approved of : in two parts, (1745). https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/FRANKLIN_9923559773503681.

- ↑ S. Doherty et al., Tracking the British Agricultural Revolution through the isotopic analysis of dated parchment, Scientific Reports, 13(1) (2023).

- ↑ L.P. de la Escosura, Exceptionalism and Industrialisation: Britain and its European Rivals, 1688-1815, (Cambridge University Press, 2011).

- ↑ 2017 - Area of woodland: changes over time, (Forest Research, 2018). https://www.forestresearch.gov.uk/tools-and-resources/statistics/forestry-statistics/forestry-statistics-2018/woodland-areas-and-planting/woodland-area-2/area-of-woodland-changes-over-time/

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 M. Thick, William Ellis, (University of Hertfordshire). https://herts.configio.com/pd/1729/william-ellis

- ↑ J. Smith, Shipbuilding and the English International Timber Trade, 1300-1700: a framework for study using Niche Construction Theory, (Digital Commons UNL, 2009).