A Compendium of Ancient Geography, Astronomy, and Medicine: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "thumb|300px|right|Marble Cover on Book. [https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/FRANKLIN_9924875933503681 A collection of two hundred and fifty coloured etchings descriptive of the manners, customs and dresses of the Hindoos] is a book authored by Balthazar Solvyns around 1799. The piece was created and published in Calcutta and currently resides in the University of Pennsylvania’s Kislak Center for Special Collections after it was accessioned i...") |

|||

| (60 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File: | [[File:FrontCoverAvenus.png|thumb|Front Cover|300px]] | ||

[https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/FRANKLIN_9931379803503681 ''Hic Codex Avienii''] is incunable published in Venice by Antonius de Strata of Cremona on October 25, 1488 (November 8, 1488 on Julian Calendar). This collection contains works by Avienus, including his adaptation of Aratus’s Phaenomena, alongside contributions from Germanicus Caesar, Cicero, and Serenus Sammonicus. This volume contains 122 unnumbered leaves, embellished with 38 [[woodcuts]], some of which are reused from earlier works. The text, set in a chancery quarto format, features 38 lines per page. This volume is a part of the University of Pennsylvania’s Kislak Center for Special Collections, offering a window into Renaissance intellectual culture and early printing techniques. | |||

[https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/ | |||

== Background == | == Background == | ||

| Line 8: | Line 6: | ||

===Historical Context=== | ===Historical Context=== | ||

This book was published in | This book was published in Venice in 1488 during a period of territorial expansion and political restructuring for the Republic of Venice. By the late 15th century, Venice had established itself as a major maritime power with vast territories on both the Italian mainland and across the eastern Mediterranean as a whole. Venice was in the process of consolidating its control of the Terraferma under the rule of Doge Giovanni Mocenigo. This consolidation was necessitated by the need to secure trade routes and counteract the territorial ambitions of regional powers like Milan and the Ottoman Empire. <ref name="Finlay">Finlay, Robert. Politics In Renaissance Venice. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1980.</ref> | ||

During this time, Venice was experiencing great commercial success. Venice was known for its successful trade routes as well as its production of luxury goods, including textiles like silk and other high quality fabrics. <ref name="Mola"> Molà, Luca, and Luca Molà. The Silk Industry of Renaissance Venice, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000.</ref> During this period, Venice emerged as a center of printing and intellectual activity. Intellectual life was flourishing throughout the city. Venice soon came to dominate not only the Italian printing industry, but the entire European printing Industry for a period. <ref name="Richard">Richardson, Brian. Printing, Writers, and Readers In Renaissance Italy. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1999.</ref> | |||

Venetian printing helped distribute Renaissance humanism throughout Europe and facilitated the exchange of knowledge. This reflects the city’s role in the cultural and intellectual status of the period.<ref name= "Richard"/> These books were not only texts, but symbols of Venetian sophistication and the cosmopolitan nature of this complex society. | |||

===Incunables in the 15th Century=== | |||

The 15th century was a transformative era for book production promoted by the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in 1450. This invention introduced the era of incunables, which represents a pivotal moment in the transition from manuscript to printed book. <ref name="Febre">Febvre, Lucien, and Henri-Jean Martin. The Coming of the Book: The Impact of Printing, 1450-1800. London: Verso, 1990.</ref> The innovations in printing technology helped mass produce books, which significantly reduced their cost and increased their accessibility. | |||

Venice became an epicenter for printing due to its strategic location and vast trade networks, which enabled the efficient distribution of books throughout Europe. Books printed in Venice were also used as exemplars by other European printers, highlighting the influence and reach of books produced in the Republic of Venice. <ref name="Jenson">Jensen, Kristian, Incunabula and Their Readers: Printing, Selling, and Using Books In the Fifteenth Century. London: British Library, 2003.</ref> The city attracted printers like Johannes de Spira and Nicolas Jenson, whose work in the 1460s helped establish the high standards for book design, especially those of Roman and Italic typefaces. While most illuminations would be ordered by the customers, Jenson’s firm ordered the illuminations himself before the book even reached the customer. <ref name="Richard"></ref> | |||

The substantial funding from its wealth merchants and nobility, supported a thriving intellectual culture that contributed to the economic status of Venice in the 15th century. This environment was conducive to the success of printing and the dissemination of new ideas. By its very nature a reading public was not only more dispersed; it was also more atomistic and individualistic than a hearing one. <ref name="Elizabeth">Eisenstein, Elizabeth L. The Printing Revolution In Early Modern Europe. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]: Cambridge University Press, 1983.</ref> For this reason, incunables often contained texts that reflected a variety of Renaissance interests in classical antiquity, religious matters, scientific explorations, and humanistic studies that catered to an increasingly diverse audience beyond just scholars. | |||

The | |||

==Material Analysis== | ==Material Analysis== | ||

===Substrate and Platform=== | ===Substrate and Platform=== | ||

This book has been | This book has been printed on rag paper in chancery quarto format, measuring 159 x 100 mm, ideal for the presentation of text accompanied by its 38 woodcut illustrations. It features signatures a<sup>10</sup> b-p<sup>8</sup> with blank leaves most likely left for note space. | ||

[[File:Title Page Solvyns.jpg|thumb|200px|left|Title Page of the Book with missing imprint piece replaced by blue strip of album paper.]] | [[File:Title Page Solvyns.jpg|thumb|200px|left|Title Page of the Book with missing imprint piece replaced by blue strip of album paper.]] | ||

===Binding=== | ===Binding=== | ||

The book | The book appears to have been rebound indicated by the presence of newer flyleaf and endpaper compared to the original pages. The current binding, like what the original would have looked like, features a wooden cover encased in leather. Although the spine is now deteriorating, it retains valuable information including the publication date and author that reveal its age and historical context. This combination of original and new elements in the binding underscores the book’s journey as well as its preservation efforts. | ||

[[File:Binding Solvyns.jpg|thumb|200px|right|Budget binding of book with gold tooling.]] | [[File:Binding Solvyns.jpg|thumb|200px|right|Budget binding of book with gold tooling.]] | ||

===Navigational Features=== | ===Navigational Features=== | ||

The book | The book uses basic navigational elements marked as a<sup>10</sup> b-p<sup>8</sup>. Using this style of navigational element that lacks modern foliation or catchwords is typical of this period. The text begins with a title and colophon that outline the book’s content and printing details. Throughout this edition of the book, lacking illuminations unlike other editions of this book, guide-letters and initial spaces help visually space the book. The inclusion of woodcuts further enhances the visual navigation. | ||

===Woodcuts=== | |||

The book features 38 woodcut illustrations within the Germanicus Caesar section. These woodcuts are notable for their historical value and their representation of the astronomical themes of the book. The origin of these illustrations is also interesting: they are reversed copies of those used in the 1485 edition of Hyginus, printed by Ratdolt. This reusing of woodcut blocks highlights the economical practices of early printers who sought to maximize available resources and profit. It was probably much cheaper to copy someone else’s, and because modern copyright laws didn’t apply, it was probably not illegal. | |||

The illustrations themselves are extremely important to understanding the content of the book, especially in conveying the complex astronomical and mythological information. The depiction of constellations helps readers visualize the celestial configurations discussed in the text. | |||

The | |||

By incorporating these visual elements, the book bridges the gap between text and visualization, allowing the reader to enhance their experience and understanding of the ancient astronomical knowledge it provides. | |||

<gallery mode="packed" perrow=4 heights=250px> | <gallery mode="packed" perrow=4 heights=250px> | ||

| Line 58: | Line 48: | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

=== | ===The Collections Within=== | ||

This incunable is a collection of classical texts that includes a collection of works by Rufius Festus Avienus, as well as adaptations by Germanicus Caesar and Cicero of Aratus’s ''Phaenomena'' that gives an introduction to the consellations. It also contains the ''Liber medicinalis'' by Serenus Sammonicus. | |||

Rufius Festus Avienus’s adaptation of the Greek poem ''Phaenomena'' extends the original text with detailed descriptions of Stoic elements, including mythological explanations for constellations, like linkin the Kneeler with Heracles. <ref name="Soubiran">Soubiran, Jean. 2003 (pr. éd. 1981). Aviénus, Les Phénomènes d’Aratos. Collection des Universités de France. Paris: Les Belles Lettres.</ref> | |||

Germanicus was a notable soldier and politician known for his Latin translation of Aratus’ ''Phaenomena''. His work reflects Rome’s rising interest in astronomy and includes precise corrections based on Hipparchus’ critiques. This edition features detailed descriptions and annotations, most notably correcting the positing of the Kneeler constellation in relation to the Dragon. <ref name="Bœuffle">Le Bœuffle, André. 2003 (pr. éd. 1975). Germanicus, Les phénomènes d’Aratos. Collection des Universités de France. Paris: Les Belles Lettres.</ref><ref name="Possanza">Possanza, D. Mark. 2004. Translating the Heavens: Aratus, Germanicus, and the Poetics of Latin Translation. Lang Classical Studies. New York: Lang.</ref> | |||

Ciceros’s early translation is noted for its similarity to the original, despite sometimes including some linguistic notes and decorative details. Cicero also utilized ancient commentaries on Aratus for clarification as seen in his descriptions and adjustments. <ref name="Bishop">Bishop, Caroline. 2016. “Naming the Roman stars: constellation etymologies in Cicero’s « Aratea » and « De natura deorum ».” Classical Quarterly N. S. 66 (1): 155-171.</ref><ref name="BishopC">Bishop, Caroline. 2019. Cicero, Greek learning, and the making of a Roman classic. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 41-84.</ref> | |||

Q. Serenus’ Liber medicinalis is a didactic poem focusing on therapy by offering remedies for around 80 diseases across 1,107 hexameters, organized into 64 chapter. The poem saw significant usage and influence, even being copied by Charlemagne, the former Holy Roman Emperor. It was even highly regarded by Humanists and throughout the modern period. <ref name="Langslow">Langslow, D. R. Medical Latin In the Roman Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.</ref> | |||

<gallery mode="packed" perrow=4 heights=250px> | <gallery mode="packed" perrow=4 heights=250px> | ||

{...} | {...} | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

==Significance== | ==Significance== | ||

== Bibliography == | == Bibliography == | ||

<references /> | |||

Latest revision as of 06:07, 11 May 2024

Hic Codex Avienii is incunable published in Venice by Antonius de Strata of Cremona on October 25, 1488 (November 8, 1488 on Julian Calendar). This collection contains works by Avienus, including his adaptation of Aratus’s Phaenomena, alongside contributions from Germanicus Caesar, Cicero, and Serenus Sammonicus. This volume contains 122 unnumbered leaves, embellished with 38 woodcuts, some of which are reused from earlier works. The text, set in a chancery quarto format, features 38 lines per page. This volume is a part of the University of Pennsylvania’s Kislak Center for Special Collections, offering a window into Renaissance intellectual culture and early printing techniques.

Background

Historical Context

This book was published in Venice in 1488 during a period of territorial expansion and political restructuring for the Republic of Venice. By the late 15th century, Venice had established itself as a major maritime power with vast territories on both the Italian mainland and across the eastern Mediterranean as a whole. Venice was in the process of consolidating its control of the Terraferma under the rule of Doge Giovanni Mocenigo. This consolidation was necessitated by the need to secure trade routes and counteract the territorial ambitions of regional powers like Milan and the Ottoman Empire. [1]

During this time, Venice was experiencing great commercial success. Venice was known for its successful trade routes as well as its production of luxury goods, including textiles like silk and other high quality fabrics. [2] During this period, Venice emerged as a center of printing and intellectual activity. Intellectual life was flourishing throughout the city. Venice soon came to dominate not only the Italian printing industry, but the entire European printing Industry for a period. [3]

Venetian printing helped distribute Renaissance humanism throughout Europe and facilitated the exchange of knowledge. This reflects the city’s role in the cultural and intellectual status of the period.[3] These books were not only texts, but symbols of Venetian sophistication and the cosmopolitan nature of this complex society.

Incunables in the 15th Century

The 15th century was a transformative era for book production promoted by the invention of the printing press by Johannes Gutenberg in 1450. This invention introduced the era of incunables, which represents a pivotal moment in the transition from manuscript to printed book. [4] The innovations in printing technology helped mass produce books, which significantly reduced their cost and increased their accessibility.

Venice became an epicenter for printing due to its strategic location and vast trade networks, which enabled the efficient distribution of books throughout Europe. Books printed in Venice were also used as exemplars by other European printers, highlighting the influence and reach of books produced in the Republic of Venice. [5] The city attracted printers like Johannes de Spira and Nicolas Jenson, whose work in the 1460s helped establish the high standards for book design, especially those of Roman and Italic typefaces. While most illuminations would be ordered by the customers, Jenson’s firm ordered the illuminations himself before the book even reached the customer. [3]

The substantial funding from its wealth merchants and nobility, supported a thriving intellectual culture that contributed to the economic status of Venice in the 15th century. This environment was conducive to the success of printing and the dissemination of new ideas. By its very nature a reading public was not only more dispersed; it was also more atomistic and individualistic than a hearing one. [6] For this reason, incunables often contained texts that reflected a variety of Renaissance interests in classical antiquity, religious matters, scientific explorations, and humanistic studies that catered to an increasingly diverse audience beyond just scholars.

Material Analysis

Substrate and Platform

This book has been printed on rag paper in chancery quarto format, measuring 159 x 100 mm, ideal for the presentation of text accompanied by its 38 woodcut illustrations. It features signatures a10 b-p8 with blank leaves most likely left for note space.

Binding

The book appears to have been rebound indicated by the presence of newer flyleaf and endpaper compared to the original pages. The current binding, like what the original would have looked like, features a wooden cover encased in leather. Although the spine is now deteriorating, it retains valuable information including the publication date and author that reveal its age and historical context. This combination of original and new elements in the binding underscores the book’s journey as well as its preservation efforts.

The book uses basic navigational elements marked as a10 b-p8. Using this style of navigational element that lacks modern foliation or catchwords is typical of this period. The text begins with a title and colophon that outline the book’s content and printing details. Throughout this edition of the book, lacking illuminations unlike other editions of this book, guide-letters and initial spaces help visually space the book. The inclusion of woodcuts further enhances the visual navigation.

Woodcuts

The book features 38 woodcut illustrations within the Germanicus Caesar section. These woodcuts are notable for their historical value and their representation of the astronomical themes of the book. The origin of these illustrations is also interesting: they are reversed copies of those used in the 1485 edition of Hyginus, printed by Ratdolt. This reusing of woodcut blocks highlights the economical practices of early printers who sought to maximize available resources and profit. It was probably much cheaper to copy someone else’s, and because modern copyright laws didn’t apply, it was probably not illegal.

The illustrations themselves are extremely important to understanding the content of the book, especially in conveying the complex astronomical and mythological information. The depiction of constellations helps readers visualize the celestial configurations discussed in the text.

By incorporating these visual elements, the book bridges the gap between text and visualization, allowing the reader to enhance their experience and understanding of the ancient astronomical knowledge it provides.

-

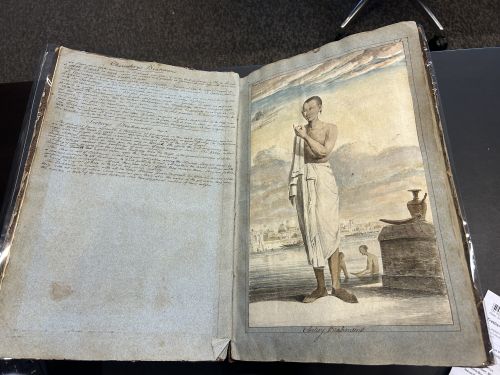

Etching with text

-

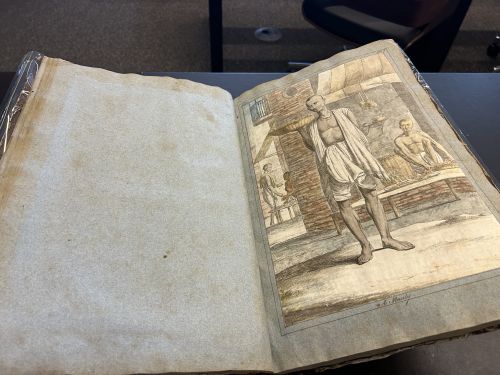

Etching without text

-

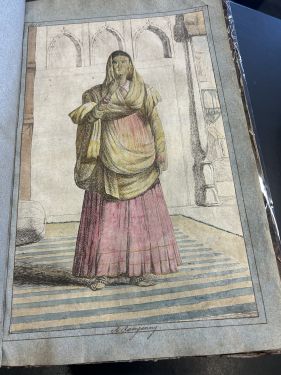

Colorful Etching of a Woman

The Collections Within

This incunable is a collection of classical texts that includes a collection of works by Rufius Festus Avienus, as well as adaptations by Germanicus Caesar and Cicero of Aratus’s Phaenomena that gives an introduction to the consellations. It also contains the Liber medicinalis by Serenus Sammonicus.

Rufius Festus Avienus’s adaptation of the Greek poem Phaenomena extends the original text with detailed descriptions of Stoic elements, including mythological explanations for constellations, like linkin the Kneeler with Heracles. [7]

Germanicus was a notable soldier and politician known for his Latin translation of Aratus’ Phaenomena. His work reflects Rome’s rising interest in astronomy and includes precise corrections based on Hipparchus’ critiques. This edition features detailed descriptions and annotations, most notably correcting the positing of the Kneeler constellation in relation to the Dragon. [8][9]

Ciceros’s early translation is noted for its similarity to the original, despite sometimes including some linguistic notes and decorative details. Cicero also utilized ancient commentaries on Aratus for clarification as seen in his descriptions and adjustments. [10][11]

Q. Serenus’ Liber medicinalis is a didactic poem focusing on therapy by offering remedies for around 80 diseases across 1,107 hexameters, organized into 64 chapter. The poem saw significant usage and influence, even being copied by Charlemagne, the former Holy Roman Emperor. It was even highly regarded by Humanists and throughout the modern period. [12]

Significance

Bibliography

- ↑ Finlay, Robert. Politics In Renaissance Venice. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1980.

- ↑ Molà, Luca, and Luca Molà. The Silk Industry of Renaissance Venice, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Richardson, Brian. Printing, Writers, and Readers In Renaissance Italy. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- ↑ Febvre, Lucien, and Henri-Jean Martin. The Coming of the Book: The Impact of Printing, 1450-1800. London: Verso, 1990.

- ↑ Jensen, Kristian, Incunabula and Their Readers: Printing, Selling, and Using Books In the Fifteenth Century. London: British Library, 2003.

- ↑ Eisenstein, Elizabeth L. The Printing Revolution In Early Modern Europe. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]: Cambridge University Press, 1983.

- ↑ Soubiran, Jean. 2003 (pr. éd. 1981). Aviénus, Les Phénomènes d’Aratos. Collection des Universités de France. Paris: Les Belles Lettres.

- ↑ Le Bœuffle, André. 2003 (pr. éd. 1975). Germanicus, Les phénomènes d’Aratos. Collection des Universités de France. Paris: Les Belles Lettres.

- ↑ Possanza, D. Mark. 2004. Translating the Heavens: Aratus, Germanicus, and the Poetics of Latin Translation. Lang Classical Studies. New York: Lang.

- ↑ Bishop, Caroline. 2016. “Naming the Roman stars: constellation etymologies in Cicero’s « Aratea » and « De natura deorum ».” Classical Quarterly N. S. 66 (1): 155-171.

- ↑ Bishop, Caroline. 2019. Cicero, Greek learning, and the making of a Roman classic. Oxford: Oxford University Press: 41-84.

- ↑ Langslow, D. R. Medical Latin In the Roman Empire. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.