A Combination Canvassing Book: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (8 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 19: | Line 19: | ||

Organized [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Book_peddler book peddlers] did not become prominent until the nineteenth century in the United States.<ref name="Hackenberg"> HACKENBERG, MICHAEL. “Hawking Subscription Books in 1870: A Salesman's Prospectus from Western Pennsylvania.” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 78, no. 2 (1984): 137–53. https://doi.org/10.1086/pbsa.78.2.24302782. </ref> This development was tied closely to the rise of [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Publication_by_subscription subscription publishing]. The system of subscription publishing involved publishers and book authors who had created a certain work giving samples to book sellers who could then travel to various locations in an attempt to sell copies. These book sellers would work door to door and within communities to convince people to purchase real copies after which their names would be added to a subscribers list. This business was especially beneficial for rural areas as there was not always a bookstore available nearby for people to have access to these books. However, subscription book selling extended beyond just rural areas, and depending on the topic of the book to be sold, the seller could have targeted very specific regions and communities. <ref name="Thomas"> Thomas, Amy M. “‘There Is Nothing so Effective as a Personal Canvass’: Revaluing Nineteenth-Century American Subscription Books.” Book History 1 (1998): 140–55. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30227285. </ref> There is a lack of information on the history of subscription book selling as not much was recorded and shared by the publishers who created these jobs. Much of what we know today regarding this profession is a result of stories that have been saved from the sellers themselves.<ref name="Hackenberg" /> Again, this system reached its peak during the nineteenth century when hundreds of thousands of subscription books were produced.<ref name="Thomas" /> A central strategy of the seller was to create a connection with each person they met. This could involve conducting some market research and using connections to better understand the community to which they were selling. Buyers had different reasons for purchasing these books. Many were actually interested in purchasing the books for the purpose of reading the material as they were interested in the actual content. Some were drawn toward the often lavish display and decoration of the books for sales. Others wanted their names to be associated with the subscribers list which for some books could hold a certain level of prestige.<ref name="Thomas" /> Regardless, subscription book selling played a role in the widespread distribution of books during this era. This system started to become less popular during the twentieth century, so this particular canvassing book is situated just before this downturn occurred. | Organized [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Book_peddler book peddlers] did not become prominent until the nineteenth century in the United States.<ref name="Hackenberg"> HACKENBERG, MICHAEL. “Hawking Subscription Books in 1870: A Salesman's Prospectus from Western Pennsylvania.” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 78, no. 2 (1984): 137–53. https://doi.org/10.1086/pbsa.78.2.24302782. </ref> This development was tied closely to the rise of [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Publication_by_subscription subscription publishing]. The system of subscription publishing involved publishers and book authors who had created a certain work giving samples to book sellers who could then travel to various locations in an attempt to sell copies. These book sellers would work door to door and within communities to convince people to purchase real copies after which their names would be added to a subscribers list. This business was especially beneficial for rural areas as there was not always a bookstore available nearby for people to have access to these books. However, subscription book selling extended beyond just rural areas, and depending on the topic of the book to be sold, the seller could have targeted very specific regions and communities. <ref name="Thomas"> Thomas, Amy M. “‘There Is Nothing so Effective as a Personal Canvass’: Revaluing Nineteenth-Century American Subscription Books.” Book History 1 (1998): 140–55. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30227285. </ref> There is a lack of information on the history of subscription book selling as not much was recorded and shared by the publishers who created these jobs. Much of what we know today regarding this profession is a result of stories that have been saved from the sellers themselves.<ref name="Hackenberg" /> Again, this system reached its peak during the nineteenth century when hundreds of thousands of subscription books were produced.<ref name="Thomas" /> A central strategy of the seller was to create a connection with each person they met. This could involve conducting some market research and using connections to better understand the community to which they were selling. Buyers had different reasons for purchasing these books. Many were actually interested in purchasing the books for the purpose of reading the material as they were interested in the actual content. Some were drawn toward the often lavish display and decoration of the books for sales. Others wanted their names to be associated with the subscribers list which for some books could hold a certain level of prestige.<ref name="Thomas" /> Regardless, subscription book selling played a role in the widespread distribution of books during this era. This system started to become less popular during the twentieth century, so this particular canvassing book is situated just before this downturn occurred. | ||

[[File:Alphabet.jpg|right|thumb|An example of illustrations being incorporated into the text from ''The Century Story Book for Our Little Ones'']] | |||

==Development of Children’s Stories== | ==Development of Children’s Stories== | ||

The introduction of books intended for children came along with the changing attitude surrounding the purpose of childhood. Following the ideas introduced by [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Locke John Locke] and [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Jacques_Rousseau Jean-Jacques Rousseau], people began to view childhood as a separate entity from adulthood. A greater emphasis was placed on giving children a space to learn and grow and celebrating their innocence and curiosity that makes that period of life distinct from adulthood. <ref name="Matulka"> Matulka, Denise I. “A Picture Book Primer: Understanding and Using Picture Books.” Google Books. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=09-XR0gKk9AC&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=early%2B20th%2Bcentury%2Blithography%2Bin%2Bchildren%27s%2Bbooks&ots=thj--5zllZ&sig=MtmSaa3bSt308XbxoArzBBO9DEc#v=onepage&q=lithography&f=false. </ref> This new philosophy paved the way for the creation of literature specifically dedicated to children. The early children’s books that arose during the seventeenth century were primarily educational but what separated them from other books for teaching was the incorporation of images. [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orbis_Pictus ''Orbis Pictus''] (1658) by [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Amos_Comenius Johannes Amos Comenius] is considered by many to be the first true picture book that was created as a textbook with images for children. Illustrated children’s books began to become more popular, but the images themselves were included more as a decoration than being directly involved in telling the story. <ref name="Tunnell"> Tunnell, Michael O., Jacobs, James S. (2013). The Origins and History of American Children's Literature. The Reading Teacher, 67( 2), 80– 86. doi: 10.1002/TRTR.1201 </ref> Many images were similar to stock images used online today and were spread across many works without the artist being highlighted. In 1865, [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alice%27s_Adventures_in_Wonderland ''Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland''] by [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lewis_Carroll Lewis Carroll] was published and is a primary example of a shift in children’s books being created for the purpose of entertainment and pleasure rather than education. The growing literate middle class of the nineteenth century provided a larger market for children’s books to be sold. <ref name="Matulka" /> This increase in literacy resulted in more parents having a desire to read and educate their children from a young age. This time period even saw the creation of bookstores that specialized in children’s literature. Additionally, the illustrators of children’s books started to come to prominence and be recognized for their work.<ref name="Matulka" /> Using a certain artist’s work began to be a selling point for these books. This growing market for children’s literature and specifically illustrated books continued into the twentieth century. | The introduction of books intended for children came along with the changing attitude surrounding the purpose of childhood. Following the ideas introduced by [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Locke John Locke] and [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jean-Jacques_Rousseau Jean-Jacques Rousseau], people began to view childhood as a separate entity from adulthood. A greater emphasis was placed on giving children a space to learn and grow and celebrating their innocence and curiosity that makes that period of life distinct from adulthood. <ref name="Matulka"> Matulka, Denise I. “A Picture Book Primer: Understanding and Using Picture Books.” Google Books. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=09-XR0gKk9AC&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=early%2B20th%2Bcentury%2Blithography%2Bin%2Bchildren%27s%2Bbooks&ots=thj--5zllZ&sig=MtmSaa3bSt308XbxoArzBBO9DEc#v=onepage&q=lithography&f=false. </ref> This new philosophy paved the way for the creation of literature specifically dedicated to children. The early children’s books that arose during the seventeenth century were primarily educational but what separated them from other books for teaching was the incorporation of images. [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orbis_Pictus ''Orbis Pictus''] (1658) by [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Amos_Comenius Johannes Amos Comenius] is considered by many to be the first true picture book that was created as a textbook with images for children. Illustrated children’s books began to become more popular, but the images themselves were included more as a decoration than being directly involved in telling the story. <ref name="Tunnell"> Tunnell, Michael O., Jacobs, James S. (2013). The Origins and History of American Children's Literature. The Reading Teacher, 67( 2), 80– 86. doi: 10.1002/TRTR.1201 </ref> Many images were similar to stock images used online today and were spread across many works without the artist being highlighted. In 1865, [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alice%27s_Adventures_in_Wonderland ''Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland''] by [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lewis_Carroll Lewis Carroll] was published and is a primary example of a shift in children’s books being created for the purpose of entertainment and pleasure rather than education. The growing literate middle class of the nineteenth century provided a larger market for children’s books to be sold. <ref name="Matulka" /> This increase in literacy resulted in more parents having a desire to read and educate their children from a young age. This time period even saw the creation of bookstores that specialized in children’s literature. Additionally, the illustrators of children’s books started to come to prominence and be recognized for their work.<ref name="Matulka" /> Using a certain artist’s work began to be a selling point for these books. This growing market for children’s literature and specifically illustrated books continued into the twentieth century. | ||

| Line 34: | Line 35: | ||

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, chromolithography and wood engraving began to get replaced by photomechanical illustration. Halftone was invented in the early 1880s by Fredereick Ives and is a process of replicating photographs where continuous tones of an image are broken up into a pattern of dots. This pattern is printed in relief and the intermediate tones of an image were created by varying the sizes of the dots. Light grays were produced as small dots and dark grays were produced as large dots. Blending these dots makes it look like there are different shades of gray in an image when in reality the image is entirely black and white. Before halftone, the average American could not afford to purchase newspapers or magazines with large amounts of color printing. <ref name="Phillips"> Phillips, David Clayton. 1996. "Art for Industry's Sake: Halftone Technology, Mass Photography and the Social Transformation of American Print Culture, 1880-1920." Order No. 9632478, Yale University. https://proxy.library.upenn.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/art-industrys-sake-halftone-technology-mass/docview/304305725/se-2. </ref> The key features of the halftone technique was that it was lower cost, required less time, and could be produced in larger quantities. All of these factors contributed to the rise of halftone in this period. In the late 1880s, it cost $300 to produce a full page colored wood engraving plate while it took less than $20 to produce the same size plate with halftone. <ref name="Phillips" /> | Toward the end of the nineteenth century, chromolithography and wood engraving began to get replaced by photomechanical illustration. Halftone was invented in the early 1880s by Fredereick Ives and is a process of replicating photographs where continuous tones of an image are broken up into a pattern of dots. This pattern is printed in relief and the intermediate tones of an image were created by varying the sizes of the dots. Light grays were produced as small dots and dark grays were produced as large dots. Blending these dots makes it look like there are different shades of gray in an image when in reality the image is entirely black and white. Before halftone, the average American could not afford to purchase newspapers or magazines with large amounts of color printing. <ref name="Phillips"> Phillips, David Clayton. 1996. "Art for Industry's Sake: Halftone Technology, Mass Photography and the Social Transformation of American Print Culture, 1880-1920." Order No. 9632478, Yale University. https://proxy.library.upenn.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/art-industrys-sake-halftone-technology-mass/docview/304305725/se-2. </ref> The key features of the halftone technique was that it was lower cost, required less time, and could be produced in larger quantities. All of these factors contributed to the rise of halftone in this period. In the late 1880s, it cost $300 to produce a full page colored wood engraving plate while it took less than $20 to produce the same size plate with halftone. <ref name="Phillips" /> | ||

<gallery widths=300px heights=400px> | |||

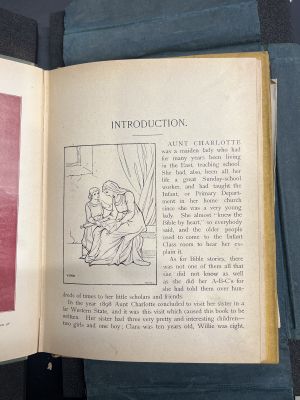

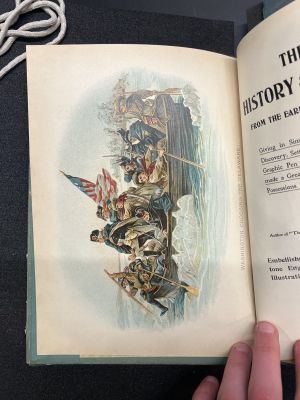

File:Woodcut.jpg|An example woodcut in text from ''Aunt Charlotte's Stories of Bible History for Young Disciples'' | |||

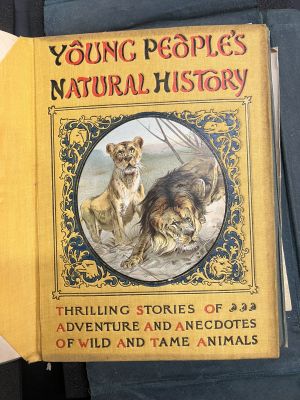

File:Litho.jpg|Colored lithograph centerpiece on the cover of ''Young People's Natural History'' | |||

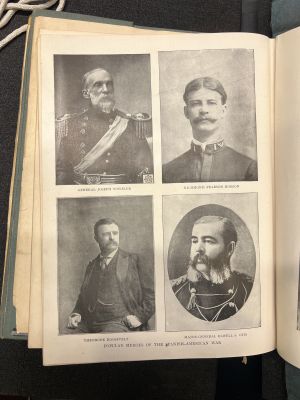

File:Portraits.jpg|Halftone portraits in ''The History and Triumphs of the Nineteenth Century'' | |||

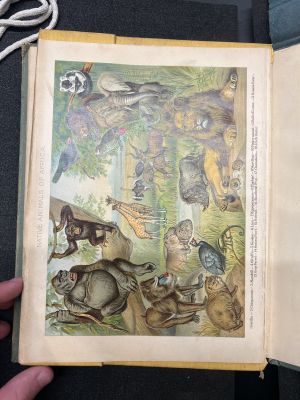

File:FullColor.jpg|Full color image in ''Young People's Natural History'' | |||

File:HalftoneColor.jpg|Halftone color plate from ''The Child's History of the United States'' | |||

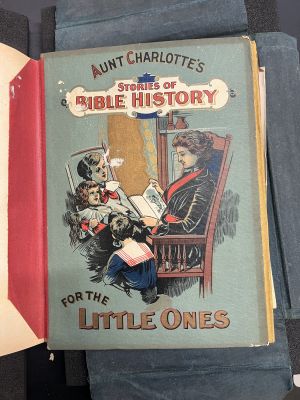

File:LithoCover.jpg|Lithograph cover from ''Aunt Charlotte's Stories of Bible History for Young Disciples'' | |||

</gallery> | |||

==Significance== | ==Significance== | ||

Latest revision as of 00:00, 8 May 2023

Overview

This combination canvassing book was created in 1900 and consists of five different children’s stories. The titles included in their given order are (1) The Century Story Book for Our Little Ones, (2) The Child's History of the United States, by Charles Morris, L.L.D., (3) Aunt Charlotte's Stories of Bible History for Young Disciples, by Charlotte M. Yonge, (4) Young People's Natural History, edited by Isaac Thorne Johnson, A.B., M.A., (5) The History and Triumphs of the Nineteenth Century, by Charles Morris, L.L.D.. All works were published by The John C. Winston Company located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The canvassing book contains specimens from each story organized appropriately and put on display for the purpose of selling full copies of the books within the subscription book business. The creator of the canvassing book is unknown and there are no markings made by the seller who would have been the owner of this book. This work is currently held at the Kislak Center for Special Collections at the University of Pennsylvania and was donated to the collection by Michael Zinman.

Physical Properties

Substrate/Format

The object itself has a green cloth exterior and is closed by flaps that bound the book shut from three of the four sides. Upon opening the book, each story is divided into its own section that includes a smaller pink slip of paper attached before the cover as an advertisement for purchasing the individual book. Each section begins with a lavishly decorated and illustrated cover that is made from wood board and covered with cloth. The design of these covers is intentional to highlight the illustrations that are one of the main selling points of these stories. Evidence of this is provided in the pink slips preceding the stories where much of the text is related to the illustrations. The pages within each story are primarily made of wood pulp however some of the pages containing images are made from other materials. Each section is made up of twenty four leaves (excluding additional flyleaves containing images) which means this book was likely created in octavo format. Despite each book being separate, the creator of this book chose to have all leaves on the same binding. As a result of its purpose, this book is relatively worn and the last story has also fallen out of the original binding. This is not surprising considering this book likely had to be packed up while traveling far distances to sell copies.

Navigating this canvassing book can be difficult without understanding how the book is divided. The decorated covers provide boundaries for the specimen from each story. Within many of the individual stories are tables of contents which provide the reader with the ability to locate chapters very easily through the use of page numbers. Additionally, some of the stories provide indices for the images they contain. With such beautifully made illustrations, and some even in full color, the publisher of these books wanted to ensure that it was easy for the reader to locate their favorite images. While a reader is unable to actually navigate to every page within the canvassing book, these navigational tools are added to show the reader what they would be able to see if they purchased the full copy.

Evidence of Use

There are no markings or signs of ownership included within the canvassing book. It was common for the specimen leaves to be delivered to the seller and they would then compile the works on their own. The Kislak Center for Special Collections at the University of Pennsylvania notes that when the book was donated, the publisher’s prospectus and subscription order leaves had been excised. These pieces could have possibly provided more information on the identity of the seller and owner of this book. However, the greatest piece of evidence that informs us of how the canvassing book was used is the pink slips that were included ahead of each individual story. These slips gave a brief explanation and a sales pitch for the book on sale. They showed the pricing for purchasing a copy and the different levels and qualities available for purchase. The highlighted feature in every pink slip was the beautiful and detailed illustrations that enhanced each story. Another important feature of these illustrations is that the artist’s themselves are credited and praised for their work. The advertising for some of these books included the names of the artists as a selling point, an advancement that had not been observed in children’s picture books until this time.

Subscription Book Selling

Organized book peddlers did not become prominent until the nineteenth century in the United States.[1] This development was tied closely to the rise of subscription publishing. The system of subscription publishing involved publishers and book authors who had created a certain work giving samples to book sellers who could then travel to various locations in an attempt to sell copies. These book sellers would work door to door and within communities to convince people to purchase real copies after which their names would be added to a subscribers list. This business was especially beneficial for rural areas as there was not always a bookstore available nearby for people to have access to these books. However, subscription book selling extended beyond just rural areas, and depending on the topic of the book to be sold, the seller could have targeted very specific regions and communities. [2] There is a lack of information on the history of subscription book selling as not much was recorded and shared by the publishers who created these jobs. Much of what we know today regarding this profession is a result of stories that have been saved from the sellers themselves.[1] Again, this system reached its peak during the nineteenth century when hundreds of thousands of subscription books were produced.[2] A central strategy of the seller was to create a connection with each person they met. This could involve conducting some market research and using connections to better understand the community to which they were selling. Buyers had different reasons for purchasing these books. Many were actually interested in purchasing the books for the purpose of reading the material as they were interested in the actual content. Some were drawn toward the often lavish display and decoration of the books for sales. Others wanted their names to be associated with the subscribers list which for some books could hold a certain level of prestige.[2] Regardless, subscription book selling played a role in the widespread distribution of books during this era. This system started to become less popular during the twentieth century, so this particular canvassing book is situated just before this downturn occurred.

Development of Children’s Stories

The introduction of books intended for children came along with the changing attitude surrounding the purpose of childhood. Following the ideas introduced by John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, people began to view childhood as a separate entity from adulthood. A greater emphasis was placed on giving children a space to learn and grow and celebrating their innocence and curiosity that makes that period of life distinct from adulthood. [3] This new philosophy paved the way for the creation of literature specifically dedicated to children. The early children’s books that arose during the seventeenth century were primarily educational but what separated them from other books for teaching was the incorporation of images. Orbis Pictus (1658) by Johannes Amos Comenius is considered by many to be the first true picture book that was created as a textbook with images for children. Illustrated children’s books began to become more popular, but the images themselves were included more as a decoration than being directly involved in telling the story. [4] Many images were similar to stock images used online today and were spread across many works without the artist being highlighted. In 1865, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll was published and is a primary example of a shift in children’s books being created for the purpose of entertainment and pleasure rather than education. The growing literate middle class of the nineteenth century provided a larger market for children’s books to be sold. [3] This increase in literacy resulted in more parents having a desire to read and educate their children from a young age. This time period even saw the creation of bookstores that specialized in children’s literature. Additionally, the illustrators of children’s books started to come to prominence and be recognized for their work.[3] Using a certain artist’s work began to be a selling point for these books. This growing market for children’s literature and specifically illustrated books continued into the twentieth century.

Illustration Techniques

The illustrations included within each of the stories was created using one of three techniques: woodcuts, lithography/chromolithography, and halftone.

Woodcuts

Woodcut printing was the oldest technique used within these stories. The process involves skilled craftsmen engraving designs into wood blocks to then be translated onto the pages. The process utilizes relief printing where ink is applied to the surface of the block and then pressed into the page carefully to produce an image. Educational woodcuts became a large part of children’s literature during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. [5] With the increase in color images being used, this process was also adapted for different colors. To create a full color image with this technique, artists had to create several blocks for different tones that would make the desired image when overlapped.

Lithography/Chromolithography

In 1819, an American printer Bass Otis first began to use lithography to produce images. Following this introduction, more printers began to experiment with how to incorporate color into this process. Lithography is a process where artists draw directly onto a stone or flat metal surface and then involves a chemical process to affix an image onto the page. Full color images could be made by creating several stones split up by color and consecutively printing them to the same page. Lithography saw financial success during its time as the primary medium which led to reduced production costs. [5] As a result, cheap pirated versions of popular English children’s books began to circulate in America. This had a negative impact on some publishers where they emphasized profit over quality and many pirated copies saw the quality of their images drop considerably. [5]

Halftone

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, chromolithography and wood engraving began to get replaced by photomechanical illustration. Halftone was invented in the early 1880s by Fredereick Ives and is a process of replicating photographs where continuous tones of an image are broken up into a pattern of dots. This pattern is printed in relief and the intermediate tones of an image were created by varying the sizes of the dots. Light grays were produced as small dots and dark grays were produced as large dots. Blending these dots makes it look like there are different shades of gray in an image when in reality the image is entirely black and white. Before halftone, the average American could not afford to purchase newspapers or magazines with large amounts of color printing. [6] The key features of the halftone technique was that it was lower cost, required less time, and could be produced in larger quantities. All of these factors contributed to the rise of halftone in this period. In the late 1880s, it cost $300 to produce a full page colored wood engraving plate while it took less than $20 to produce the same size plate with halftone. [6]

-

An example woodcut in text from Aunt Charlotte's Stories of Bible History for Young Disciples

-

Colored lithograph centerpiece on the cover of Young People's Natural History

-

Halftone portraits in The History and Triumphs of the Nineteenth Century

-

Full color image in Young People's Natural History

-

Halftone color plate from The Child's History of the United States

-

Lithograph cover from Aunt Charlotte's Stories of Bible History for Young Disciples

Significance

The combination canvassing book is situated at an important time in the development of illustrated children’s books and the development of new image printing techniques. While the intention of most of these stories may be generally educational, it is important to note that the images are incorporated into the stories and text rather than just being side pieces for decoration. Credit is given to the artists who made the illustrations and they are highlighted in the pink slips preceding each section. These stories were all made just for children which will impact the way in which they were sold. When a book salesman arrived at the door they would not be selling to the child who would ultimately read or be read aloud the book but instead to their parents. The pitch would likely need to convey the importance of educating and reading to children in order to persuade the parents to purchase a copy. It is difficult to know where exactly the target region would be for these books. The publisher was located in Philadelphia, however, the goal of subscription publishing and traveling book salesmen was to reach a larger audience. This canvassing book is also an example of the transition in image printing techniques occurring at this time. Older techniques such as woodcut engravings are still included, while newer, more efficient and cost effective methods such as chromolithography and halftone are used more frequently. This emphasis on the cost effectiveness of image reproduction is important because it also allows for more widespread purchase of books and other printed works containing illustrations. It is far easier for a traveling salesman to convince a buyer to purchase a beautifully illustrated book if it comes with a reasonable price. This combination canvassing book provides an interesting insight into the history of subscription book selling, the development of children’s picture books, and the illustration techniques of the nineteenth and early twentieth century.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 HACKENBERG, MICHAEL. “Hawking Subscription Books in 1870: A Salesman's Prospectus from Western Pennsylvania.” The Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America 78, no. 2 (1984): 137–53. https://doi.org/10.1086/pbsa.78.2.24302782.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Thomas, Amy M. “‘There Is Nothing so Effective as a Personal Canvass’: Revaluing Nineteenth-Century American Subscription Books.” Book History 1 (1998): 140–55. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30227285.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Matulka, Denise I. “A Picture Book Primer: Understanding and Using Picture Books.” Google Books. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2008. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=09-XR0gKk9AC&oi=fnd&pg=PR7&dq=early%2B20th%2Bcentury%2Blithography%2Bin%2Bchildren%27s%2Bbooks&ots=thj--5zllZ&sig=MtmSaa3bSt308XbxoArzBBO9DEc#v=onepage&q=lithography&f=false.

- ↑ Tunnell, Michael O., Jacobs, James S. (2013). The Origins and History of American Children's Literature. The Reading Teacher, 67( 2), 80– 86. doi: 10.1002/TRTR.1201

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 ROYLANCE, DALE. “The Graphic Art of Children’s Book Illustration in America, 1840-1880.” The Princeton University Library Chronicle 45, no. 3 (1984): 256–66. https://doi.org/10.2307/26402396.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Phillips, David Clayton. 1996. "Art for Industry's Sake: Halftone Technology, Mass Photography and the Social Transformation of American Print Culture, 1880-1920." Order No. 9632478, Yale University. https://proxy.library.upenn.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/art-industrys-sake-halftone-technology-mass/docview/304305725/se-2.