Recipe book: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

Image:Back Cover.jpeg| (The back cover / last page of the book) | Image:Back Cover.jpeg| (The back cover / last page of the book) | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

It has a leather cover for both the front and back with a limp vellum binding. The book seems like it was written on a nice notebook at the time considering how old it has been and how much it would have been passed on from one individual to another. The material | It has a leather cover for both the front and back with a limp vellum binding. The book seems like it was written on a nice notebook at the time considering how old it has been and how much it would have been passed on from one individual to another. The material on the inside of the book is white paper with lines on it. | ||

<gallery mode="traditional"> | <gallery mode="traditional"> | ||

Image:Stain 1.jpeg| (Stains in the corners of each page) | Image:Stain 1.jpeg| (Stains in the corners of each page) | ||

| Line 96: | Line 96: | ||

== Historical Significance == | == Historical Significance == | ||

Recipe books are valuable historical sources that reveal far more than just the recipes that people followed. They provide insights into literacy, authorship, and domesticity. The popularity of recipe books relate to the growth in culinary literature and how it characterizes the social phenomena in England. <ref> Lehmann, Gilly. The British Housewife: Cookery Books, Cooking and Society in Eighteenth-Century England. Totnes: Prospect Books, 2003. </ref> | |||

=== Authorship === | === Authorship === | ||

The receipt books were mostly written by women | Increasing literacy, the rise of the middle class, and the growing popularity of the “how to” genre led to the publication of many recipe books. The receipt books were mostly written by women. Creating these manuscripts allowed women to practice writing and offer literacy to the female population during the early modern period when more males were educated than women. In particular, female literacy during this time is estimated to be 10 percent in 1640,<ref> Cressy, David. Literacy and the Social Order : Reading and Writing in Tudor and Stuart England. Cambridge [Eng.] ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1980. </ref> Thus, recipe books provide great insight into women’s authorship. Moreover, recipe books allow women to be able to portray self-expression and creativity. | ||

=== Domesticity === | === Domesticity === | ||

Latest revision as of 22:00, 3 May 2023

Overview

The Recipe Book is a manuscript cookbook written by various women in England between the years 1600 and 1825.[1] In some ways, there is no official "publisher" – someone who makes public a text – since it is not physically written on the book. The receipt book genre was popular during the early modern period, and this book contains entries for various recipes, ways to preserve food, remedies, and household tips. Housewives shared recipes and household tips with other housewives and passed them on to their daughters. The circulation of the book was casual and private. Therefore, it can be assumed that the book was owned by many women. The book also provides insights into authorship and the role of women in English society during the 17-18th century. The book was owned by King Alfred's Notebook (Cayce, S.C.), and University of Pennsylvania acquired it in 2011. The book can be found at the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts.

Background

Historical Context

Receipt books, also called recipe books or manuscript cookbooks, were domestic manuals of recipes and remedies. They became popular in the early modern period in England, and these books were typically written by and circulated among housewives.[2] There were no printed recipe books in the beginning, and in the first half of the 17th century, they started to circulate. During this time, there also were diverse authors of how-to books on medical practice and surgery. [3] Female authors wrote down and shared their native English recipes in their recipe books. As the century progressed, the content of the books started to include medical instructions and household tips. By the end of the 18th century, recipe books also included heavy doses of servant etiquette and moral advice. At this time plain English fare had replaced French cuisine. Recipe books of French cuisine were popular among wealthy households who employed French chefs as status symbols. In the mid-19th century, recipe books started to target the working classes as well. [4]

Author

The book is known to be written in England in the first half of the 17th century (f. 1-48), with additions from the 17th through early 19th centuries (f. 49-86). It is known that the first part of the book is the secretary hand (f. 1-48) and the later is cursive hands (f. 49-86). Since there are various handwritings, it can be assumed that more than one woman wrote the book. Elizabeth Grey, Countess of Kent is known as one of the contributors of the book. While her handwriting is not physically in the book, she is known as a contributor. As a medical recipe collector, she wrote cures for pox, plague, and other common illnesses as well as recipes for culinary treats. The highly educated Lady Kent was known in elite circles as a collector of medical remedies. [5]

Physical Analysis

Metadata

Date / Time Period

- Not physically written in the book

- Known to be from around 1600-1825

Place

- Not physically written in the book

- Known to be written in England

Publisher

- Not physically written in the book

- In some ways, there is no really an official "publisher" -- someone who makes public a text

- It is known that women who were responsible for cooking and maintaining the house wrote the book to share with other women and pass down to their daughters

- Various handwritings indicate that the book is written by more than one woman

Copyright / Licensing

- There is no evidence that this object was copyrighted or licensed

Provenance

- The book was owned by King Alfred's Notebook (Cayce, S.C.), and Penn acquired it in 2011

Book as Physical Object

Substrate

-

(The front cover / title page of the book)

-

(Typical page in the book/ paper and lines on it)

-

(The back cover / last page of the book)

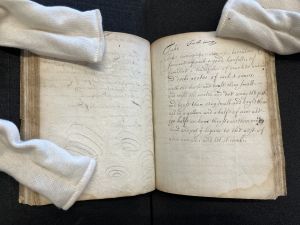

It has a leather cover for both the front and back with a limp vellum binding. The book seems like it was written on a nice notebook at the time considering how old it has been and how much it would have been passed on from one individual to another. The material on the inside of the book is white paper with lines on it.

-

(Stains in the corners of each page)

-

(Stains in the corners of each page)

While there are water stains on every page of the book in both the top and the bottom corners of the book, considering the age and use of the book, it is in good condition.

Platform/ Format

This book object is a codex, and its bibliographic format is quarto. It is a modern foliation in pencil, lower right recto. It has a shape and format of a normal book with rectangular pages that open up with two pages each. One difference between this book and a typical book is that this book can be read either from the front or the back.

Binding/ Structure

-

(Limp vellum binding)

-

(Side)

-

(Binding)

The object is bounded. It is limp vellum binding, which indicates that this book is original. The binding seems to be of contemporary parchment, with two sets of ties.

-

(Typical page in the book, current page is for recipes #13 and #14)

-

(In the later part of the book, the writings are upside-down)

There is a subtitle on every page of the book indicating what the page will explain. For example, it says “For Stewed Meats,” For Sore Eyes,” and etc. The subtitle on every page helps the reader easily know what the page is talking about. There is a clear structure where all cooking recipes are grouped together. Then, the other side of the book has the medical cures. Furthermore, the subtitles help the reader navigate: one might want to find instructions for a specific food or ways of doing something, and they can easily do so by looking at the subtitles. These subtitles correspond to the table of contents. While the book does not follow the table of content as page numbers, it follows the number label of the recipe. For example, the image shows recipes #13 and #14. While this page may not be the 13th page of the book, the subtitle recipe and number match the table of contents. It is interesting to see that the later part of the book is written upside-down. This almost divides the book in two where the first part is more about the recipe for cooking and the second part is about receipt for doing other things, such as medical cures.

Paratexts

-

(Table of Content 1-79 – in the beginning of the book)

-

(Table of Content 1-79 – in the beginning of the book)

-

(Table of Content 1-33 written upside-down – at the end of the book)

There is no paratext for preface or dedication, but they have an index. There is a table of contents keyed to the numbers of the recipes from number 1 to 79. The table of contents is divided into smaller sections with titles, such as “For Boil'd meats,” “For stewed Meats,” “To make Pasts (pastries),” “Roast Meats,” “Fryed Meats,” “Sauced Meats,” “To Make Tarts,” and “Milk Meats (including puddings).” Then, as mentioned earlier when describing how the later part of the book is written upside-down, there is another table of contents at the end of the book that is also written upside-down (which is about all the content written upside-down which are of medical cures). The division of the book provides a clue as to when certain parts were made as mentioned earlier. The first part was written in secretary hand in the first half of the 17th century (f. 1-48), with additions from the 17th through early 19th centuries (f. 49-86) written in cursive hands.

Book Use

Marginalia / Annotations

The recipes in this first part of the book are closely related to the recipes of Elizabeth Grey, Countess of Kent, published in 1653 and 1687. In this early section, few recipes for perfumes and cures (including for consumption, sore eyes, and heartburn) have been added later by different handwriting on blank versos or in lower margins.

The second half of the book, which is known to be written in 17th- to early 19th-century, has more information about various recipes, primarily medicinal (f. 49-63). It contains cures for scurvy (attributed to Doctor Short), jaundice, and toothache. It includes culinary recipes here and there (occasionally) with instructions for preserving lemons, making elder vinegar and cherry brandy, and pickling cucumbers. These are written upside down (f. 64-86). Additionally, the first page at the end (f. 86v) is a table of contents that does not correspond to the recipes in the manuscript. It contains information about medicinal recipes (including for worms, bleeding, eye complaints, burns, coughs, another cure for scurvy attributed to Dr. Short, and purgatives) and a few culinary recipes.

Marks

On the very first page of the book when you turn the title page, it has no written content. Yet, it has asemic marks that almost look like a child’s drawings. One is of repetitive marks of a figure that could look like an alphabet “p” or a balloon. Another is like a puzzle that has one long line with square and circular shapes around it. In the middle of the book, there also are three consecutive pages with asemic marks that are almost identical. It is like a drawing of a tornado. This almost looks like a child’s doodles. Since this book is assumed to be passed onto daughters from housewives, children may have doodled on the book when in their possession. It can also be assumed that while the mothers were cooking or following the recipe, children came nearby and were doodling on the book. On the other hand, since this book is a more casual book for the purpose of sharing information on how to cook different food and do various house duties, the authors of the book could have used the pages of the books for pen trials -- when the ink of a pen does not come out.

Historical Significance

Recipe books are valuable historical sources that reveal far more than just the recipes that people followed. They provide insights into literacy, authorship, and domesticity. The popularity of recipe books relate to the growth in culinary literature and how it characterizes the social phenomena in England. [6]

Authorship

Increasing literacy, the rise of the middle class, and the growing popularity of the “how to” genre led to the publication of many recipe books. The receipt books were mostly written by women. Creating these manuscripts allowed women to practice writing and offer literacy to the female population during the early modern period when more males were educated than women. In particular, female literacy during this time is estimated to be 10 percent in 1640,[7] Thus, recipe books provide great insight into women’s authorship. Moreover, recipe books allow women to be able to portray self-expression and creativity.

Domesticity

Since recipe books were known to be read and shared casually among housewives, many of them used these books on a daily basis to follow recipes for cooking and/or making cures. The instructions for these everyday dishes are not in standard/mathematical measurements, but rather in consistency measurements like "stir until the consistency of paste" or "a pinch of sugar." This shows how recipe books were more of a private, casual, and intimate source of a place to write down and learn about household tips. It is important to recognize that these books are not meant to be analyzed or read carefully. These books shed light on the close relationship between the role of women and domesticity during the early modern period in England. Perhaps, it can be assumed that the role of women in English society was a person in charge of household duties. This recipe book demonstrates how women (often marginalized by gender) could use the recipe book as a rhetorical space to share different ideas/recipes and discuss domesticity.

References

- ↑ https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/FRANKLIN_9950173773503681

- ↑ Kowalchuk, Kristine. Preserving on Paper: Seventeenth-Century Englishwomen’s Receipt Books. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2017.

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ArT_uJgELUI&t=18s

- ↑ https://janeausten.co.uk/blogs/regency-history/18th-century-cookery-books-and-the-british-housewife

- ↑ https://www.manuscriptcookbookssurvey.org/collection/index.php/Detail/manuscripts/158

- ↑ Lehmann, Gilly. The British Housewife: Cookery Books, Cooking and Society in Eighteenth-Century England. Totnes: Prospect Books, 2003.

- ↑ Cressy, David. Literacy and the Social Order : Reading and Writing in Tudor and Stuart England. Cambridge [Eng.] ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1980.