Minnie Recipe Book: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (57 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

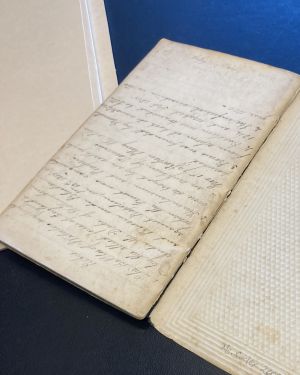

The '''Minnie Recipe Book''' is a manuscript cookbook written by Minnie, a woman from England, between the years 1872 and 1920.<ref>https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/FRANKLIN_9977524307603681</ref> As part of the receipt book genre that was popular during the early modern period, the book contains entries for various recipes, knitting patterns, remedies, and household tips. The manuscript also contains marginal notes and a few notes about historical events. The book provides insight into women’s authorship and the role of women in English society. In 2019, the manuscript was sold by Alastor Rare Books in England to the [https://www.library.upenn.edu/kislak Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts] at the [https:// | [[File:MinnieRecipeBookFront.JPG|thumb|right|Front cover]] The '''Minnie Recipe Book''' is a manuscript cookbook written by Minnie, a woman from England, between the years 1872 and 1920.<ref name="catalog entry">https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/FRANKLIN_9977524307603681</ref> As part of the receipt book genre that was popular during the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Early_modern_period early modern period], the book contains entries for various recipes, knitting patterns, remedies, and household tips. The [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manuscript manuscript] also contains marginal notes and a few notes about historical events. The book provides insight into women’s authorship and the role of women in English society. In 2019, the manuscript was sold by Alastor Rare Books in England to the [https://www.library.upenn.edu/kislak Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts] at the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/University_of_Pennsylvania University of Pennsylvania] in Philadelphia, where it now resides. | ||

==Background== | ==Background== | ||

===Historical context | ===Historical context=== | ||

Receipt books, also called manuscript cookbooks, were domestic manuals of recipes, remedies and household tips, typically written and used by women. Manuscript cookbooks began popping up in England in the mid-1600s, with some of the earliest being created in 1625. Around this time, the word “receipt” became the term for a set of ingredients, instructions, or procedures for the preparation of food or drink, <ref>https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/159401?rskey=12nMdW&result=1#eid </ref> and these books became known as “receipt books.” Today, “recipe” has come to mean the same as “receipt,” and academics refer to the receipt book as manuscript cookbooks.<ref>https://www.manuscriptcookbookssurvey.org/essays/553/</ref> | ====The receipt book==== | ||

Receipt books, also called manuscript cookbooks, were domestic manuals of recipes, remedies and household tips, typically written and used by women.<ref name="preserving on paper">Kowalchuk, Kristine. Preserving on Paper: Seventeenth-Century Englishwomen’s Receipt Books. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2017. </ref> Unlike most printed cookbooks, manuscript cookbooks often contained additional culinary and cultural knowledge such as ingredient substitutions or popular ways to present dishes.<ref name="culinary historians of ny">"What We Can Learn From Manuscript Cookbooks." Culinary Historians of New York. Accessed May 4, 2022. https://www.culinaryhistoriansny.org/program-summary/what-we-can-learn-from-manuscript-cookbooks-2/.</ref> Manuscript cookbooks began popping up in England in the mid-1600s, with some of the earliest being created in 1625. Around this time, the word “receipt” became the term for a set of ingredients, instructions, or procedures for the preparation of food or drink, <ref>"Recipe," Oxford English Dictionary, accessed April 18, 2022, https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/159401?rskey=12nMdW&result=1#eid </ref> and these books became known as “receipt books.” Today, “recipe” has come to mean the same as “receipt,” and academics refer to the receipt book as manuscript cookbooks.<ref name="Manuscript Cookbooks Survey">Schmidt, Stephen. "What Manuscript Cookbooks Can Tell Us that Printed Cookbooks Do Not." Manuscript Cookbooks Survey, May 2015. https://www.manuscriptcookbookssurvey.org/essays/553/</ref> The genre was largely popular throughout the mid-nineteenth century, with the Minnie recipe book having been created toward the end of the receipt book era. | |||

===Content=== | ===Content=== | ||

The Minnie recipe book was written in a small, faded dark green bound notebook. Minnie, the author of this manuscript cookbook, filled the pages with entries starting in 1872 and ending in 1920. The first 53 pages have been numbered by hand, and an unfinished index takes up the rest of the pages. There’s a variety of food recipes (such as ones for puddings, cakes, and baking soda), knitting patterns (for a baby hat, socks, and specific stitches and techniques), medicine (including one for a cough mixture), and other household tips (such as how to hold a piece of paper into a drinking cup or how to get rid of flies). Written upside down on the last page of the book are a series of four notes about historical events, such as the Battle of Waterloo. | [[File:MinnieRecipeBookHistNotes.JPG|thumb|right|History notes written upside down on the last page]] | ||

The Minnie recipe book was written in a small, faded dark green bound notebook. Minnie, the author of this manuscript cookbook, filled the pages with entries starting in 1872 and ending in 1920. The first 53 pages have been numbered by hand, and an unfinished index takes up the rest of the pages. There’s a variety of food recipes (such as ones for puddings, cakes, and baking soda), knitting patterns (for a baby hat, socks, and specific stitches and techniques), medicine (including one for a cough mixture), and other household tips (such as how to hold a piece of paper into a drinking cup or how to get rid of flies). Written upside down on the last page of the book are a series of four notes about historical events, such as the Battle of Waterloo. | |||

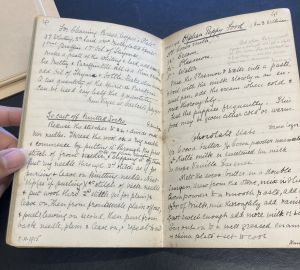

There’s no sense of organization or categorization to the order of the entries; the first page reads “Receipts” at the top, and no other pages have specific headers. After that first heading, the first entry describes how to remove stains from your hands before immediately jumping into a recipe for soda cake. Similarly, the entries on the other pages follow no logical order. Each entry begins right after the other, with just one line skipped to separate them, regardless of the type of entry. For instance, pages 40-41 include the following entries back to back: | There’s no sense of organization or categorization to the order of the entries; the first page reads “Receipts” at the top, and no other pages have specific headers. After that first heading, the first entry describes how to remove stains from your hands before immediately jumping into a recipe for soda cake. Similarly, the entries on the other pages follow no logical order. Each entry begins right after the other, with just one line skipped to separate them, regardless of the type of entry. For instance, pages 40-41 include the following entries back to back: [[File:MinnieRecipeBookpg4041.JPG|thumb|right|Pages 40-41]] | ||

*For Gleaming Brass, Copper + Plate | *For Gleaming Brass, Copper + Plate | ||

*To cast off Knitted Socks | *To cast off Knitted Socks | ||

| Line 16: | Line 18: | ||

===Author(s)=== | ===Author(s)=== | ||

No information is known about Minnie, aside from her being | [[File:MinnieRecipeBookToDestroyFlies.JPG|thumb|right|"To destroy Flies" (pg. 39)]] | ||

No information is known about Minnie, aside from her being an author of this manuscript. The Penn Libraries catalog entry for the Minnie recipe book notes Minnie as the sole author of the manuscript.<ref name="catalog entry"/> However, there are at least two handwriting styles throughout the notebook, indicating that the manuscript was passed on to a second owner who continued compiling entries, which would make sense given the long range of time between the first and last entry. It's unclear which hand was Minnie's. The history notes found at the end of the book were written by a third hand — either written before the recipes or added after the recipe entries began; either way, this inclusion indicates that one of the notebook's owners repurposed the book. | |||

The first set of entries, written by the earlier hand, uses line separators in between each. The second author's handwriting is less neat and their entries contain more corrections and ink smudges. In terms of content, though, the majority of the entries were written by the second hand, and these contain more knitting patterns and techniques, whereas the first author primarily focused on food recipes such as cakes and puddings. Both authors included a roughly equal amount of household tips. | |||

====Collaborative history==== | |||

Many of the entries by the second author include attributions and dates for many of them, yet even so, the format of the dates are inconsistent. “To destroy Flies” on page 39, for example, includes a citation to a text called “Countryside” and is dated “13•IX•12” while the entry right above it, "Brioche Pattern for Knitting Scarfs + Petticoats" is dated "Sep 27, 1914." The second author appears to have used the manuscript cookbook to record recipes found in other published cookbooks or from other writers, as many of their entries contain attributions to outside sources. It wasn't uncommon for manuscript cookbook authors to copy recipes from other cookbooks and collections.<ref name="Manuscript Cookbooks Survey" /> | |||

Many of the second author's entries also have annotations written in pencil (which can be seen in the image for pages 40-41), usually to the side of the ingredient lists to suggest a different ingredient amount, though sometimes the pencil markings feature additional notes for the recipe and are dated. It's difficult to tell whether the pencil marks were made by the second author of the book or by a later owner of the manuscript, though it was common for receipt book authors to add notes and annotations to recipes they had copied down from other sources. | |||

These features of the Minnie recipe book are in line with the idea of receipt books as highly collaborative manuscripts.<ref name="preserving on paper"/> | |||

===Readership=== | ===Readership=== | ||

During the early modern period, it was common for manuscripts to circulate among the family and friends of the original author; inscriptions would often be left as the book passed from person to person, providing evidence of its circulation.<ref name="help"> Wall, Wendy. Recipes for Thought: Knowledge and Taste in the Early Modern English Kitchen. | |||

Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015.</ref> However, the Minnie recipe book contains no such evidence of circulation — it’s unlikely that this book would have been circulated or read by anyone outside of Minnie’s household or family. It appears that this manuscript was created as a reference for the author's personal use, and unlike a select few manuscript cookbooks, this book was never published. | |||

==Historical significance== | ==Historical significance== | ||

===Women's literacy and authorship=== | ===Women's literacy and authorship=== | ||

The majority of manuscript cookbooks were written by women | The majority of manuscript cookbooks were written by women. In many cases, creating these manuscripts were ways for women to practice writing and gain literacy. [[File:MinnieRecipeBookIndex.JPG|thumb|right|The unfinished index contains evidence of the author experimenting with handwriting styles and design]]Female literacy during the early modern period is typically believed to be quite low, with scholars estimating it to be 10 percent in 1640,<ref> Cressy, David. Literacy and the Social Order : Reading and Writing in Tudor and Stuart England. Cambridge [Eng.] ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1980. </ref> and when considering female authorship in the early modern period and up until the twentieth century, you wouldn’t expect to find many books written by women. However, as scholars have begun to question the methodology behind female literacy and expand our definitions and understanding of literacy and authorship<ref name="help"/> it seems that this isn’t quite the case — there were plenty of female writers, but not many were published. Instead, you’ll find many handwritten manuscripts, and though they may not be literary in nature, these works still provide great insight into women’s authorship.<ref name="preserving on paper"/> | ||

===Domesticity and self-expression=== | |||

Manuscript cookbooks are "explicit emblems of women's relegation to the domestic sphere."<ref name="narrative theory">Newlyn, Andrea K. “Challenging Contemporary Narrative Theory: The Alternative Textual | |||

Strategies of Nineteenth-Century Manuscript Cookbooks.” Journal of American Culture 22, no. 3 (1999): 35-47. </ref> Handwriting became ingrained in housewifery just as much as the association between women, the kitchen, and domesticity, yet the genre of the receipt book still allowed for self-expression and inventiveness when it came to deciding the content of the manuscript, whether that be the types of entries included or doodles or designs.<ref name="help"/> | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Latest revision as of 10:34, 5 May 2022

The Minnie Recipe Book is a manuscript cookbook written by Minnie, a woman from England, between the years 1872 and 1920.[1] As part of the receipt book genre that was popular during the early modern period, the book contains entries for various recipes, knitting patterns, remedies, and household tips. The manuscript also contains marginal notes and a few notes about historical events. The book provides insight into women’s authorship and the role of women in English society. In 2019, the manuscript was sold by Alastor Rare Books in England to the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, where it now resides.

Background

Historical context

The receipt book

Receipt books, also called manuscript cookbooks, were domestic manuals of recipes, remedies and household tips, typically written and used by women.[2] Unlike most printed cookbooks, manuscript cookbooks often contained additional culinary and cultural knowledge such as ingredient substitutions or popular ways to present dishes.[3] Manuscript cookbooks began popping up in England in the mid-1600s, with some of the earliest being created in 1625. Around this time, the word “receipt” became the term for a set of ingredients, instructions, or procedures for the preparation of food or drink, [4] and these books became known as “receipt books.” Today, “recipe” has come to mean the same as “receipt,” and academics refer to the receipt book as manuscript cookbooks.[5] The genre was largely popular throughout the mid-nineteenth century, with the Minnie recipe book having been created toward the end of the receipt book era.

Content

The Minnie recipe book was written in a small, faded dark green bound notebook. Minnie, the author of this manuscript cookbook, filled the pages with entries starting in 1872 and ending in 1920. The first 53 pages have been numbered by hand, and an unfinished index takes up the rest of the pages. There’s a variety of food recipes (such as ones for puddings, cakes, and baking soda), knitting patterns (for a baby hat, socks, and specific stitches and techniques), medicine (including one for a cough mixture), and other household tips (such as how to hold a piece of paper into a drinking cup or how to get rid of flies). Written upside down on the last page of the book are a series of four notes about historical events, such as the Battle of Waterloo.

There’s no sense of organization or categorization to the order of the entries; the first page reads “Receipts” at the top, and no other pages have specific headers. After that first heading, the first entry describes how to remove stains from your hands before immediately jumping into a recipe for soda cake. Similarly, the entries on the other pages follow no logical order. Each entry begins right after the other, with just one line skipped to separate them, regardless of the type of entry. For instance, pages 40-41 include the following entries back to back:

- For Gleaming Brass, Copper + Plate

- To cast off Knitted Socks

- Orphan Puppy Food

- Chocolate Slabs

Author(s)

No information is known about Minnie, aside from her being an author of this manuscript. The Penn Libraries catalog entry for the Minnie recipe book notes Minnie as the sole author of the manuscript.[1] However, there are at least two handwriting styles throughout the notebook, indicating that the manuscript was passed on to a second owner who continued compiling entries, which would make sense given the long range of time between the first and last entry. It's unclear which hand was Minnie's. The history notes found at the end of the book were written by a third hand — either written before the recipes or added after the recipe entries began; either way, this inclusion indicates that one of the notebook's owners repurposed the book.

The first set of entries, written by the earlier hand, uses line separators in between each. The second author's handwriting is less neat and their entries contain more corrections and ink smudges. In terms of content, though, the majority of the entries were written by the second hand, and these contain more knitting patterns and techniques, whereas the first author primarily focused on food recipes such as cakes and puddings. Both authors included a roughly equal amount of household tips.

Collaborative history

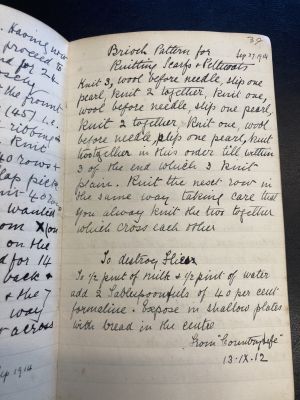

Many of the entries by the second author include attributions and dates for many of them, yet even so, the format of the dates are inconsistent. “To destroy Flies” on page 39, for example, includes a citation to a text called “Countryside” and is dated “13•IX•12” while the entry right above it, "Brioche Pattern for Knitting Scarfs + Petticoats" is dated "Sep 27, 1914." The second author appears to have used the manuscript cookbook to record recipes found in other published cookbooks or from other writers, as many of their entries contain attributions to outside sources. It wasn't uncommon for manuscript cookbook authors to copy recipes from other cookbooks and collections.[5]

Many of the second author's entries also have annotations written in pencil (which can be seen in the image for pages 40-41), usually to the side of the ingredient lists to suggest a different ingredient amount, though sometimes the pencil markings feature additional notes for the recipe and are dated. It's difficult to tell whether the pencil marks were made by the second author of the book or by a later owner of the manuscript, though it was common for receipt book authors to add notes and annotations to recipes they had copied down from other sources.

These features of the Minnie recipe book are in line with the idea of receipt books as highly collaborative manuscripts.[2]

Readership

During the early modern period, it was common for manuscripts to circulate among the family and friends of the original author; inscriptions would often be left as the book passed from person to person, providing evidence of its circulation.[6] However, the Minnie recipe book contains no such evidence of circulation — it’s unlikely that this book would have been circulated or read by anyone outside of Minnie’s household or family. It appears that this manuscript was created as a reference for the author's personal use, and unlike a select few manuscript cookbooks, this book was never published.

Historical significance

Women's literacy and authorship

The majority of manuscript cookbooks were written by women. In many cases, creating these manuscripts were ways for women to practice writing and gain literacy.

Female literacy during the early modern period is typically believed to be quite low, with scholars estimating it to be 10 percent in 1640,[7] and when considering female authorship in the early modern period and up until the twentieth century, you wouldn’t expect to find many books written by women. However, as scholars have begun to question the methodology behind female literacy and expand our definitions and understanding of literacy and authorship[6] it seems that this isn’t quite the case — there were plenty of female writers, but not many were published. Instead, you’ll find many handwritten manuscripts, and though they may not be literary in nature, these works still provide great insight into women’s authorship.[2]

Domesticity and self-expression

Manuscript cookbooks are "explicit emblems of women's relegation to the domestic sphere."[8] Handwriting became ingrained in housewifery just as much as the association between women, the kitchen, and domesticity, yet the genre of the receipt book still allowed for self-expression and inventiveness when it came to deciding the content of the manuscript, whether that be the types of entries included or doodles or designs.[6]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/FRANKLIN_9977524307603681

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Kowalchuk, Kristine. Preserving on Paper: Seventeenth-Century Englishwomen’s Receipt Books. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2017.

- ↑ "What We Can Learn From Manuscript Cookbooks." Culinary Historians of New York. Accessed May 4, 2022. https://www.culinaryhistoriansny.org/program-summary/what-we-can-learn-from-manuscript-cookbooks-2/.

- ↑ "Recipe," Oxford English Dictionary, accessed April 18, 2022, https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/159401?rskey=12nMdW&result=1#eid

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Schmidt, Stephen. "What Manuscript Cookbooks Can Tell Us that Printed Cookbooks Do Not." Manuscript Cookbooks Survey, May 2015. https://www.manuscriptcookbookssurvey.org/essays/553/

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Wall, Wendy. Recipes for Thought: Knowledge and Taste in the Early Modern English Kitchen. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015.

- ↑ Cressy, David. Literacy and the Social Order : Reading and Writing in Tudor and Stuart England. Cambridge [Eng.] ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1980.

- ↑ Newlyn, Andrea K. “Challenging Contemporary Narrative Theory: The Alternative Textual Strategies of Nineteenth-Century Manuscript Cookbooks.” Journal of American Culture 22, no. 3 (1999): 35-47.