Anatomy of the Human Body: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

===William Cheselden=== | ===William Cheselden=== | ||

[[File:Download.webp|thumb|200px|right|William Cheselden]] | [[File:Download.webp|thumb|200px|right|William Cheselden]] | ||

[https://www.britannica.com/biography/William-Cheselden "William Cheselden"] (Oct. 19, 1688 - Apr. 10, 1752) was a British surgeon and teacher. He was an important figure in revolutionizing and establishing surgery as a profession within the medical field. Cheselden was elected as a fellow of the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Society "Royal Society"] of London for Improving Natural Knowledge in 1712. It was following this when he was a teacher of anatomy and surgery, highlighted by the publishing of his anatomical atlas Anatomy of the Human Body (1792). He recognized a need for the development of formal anatomy coursework. He studied and was apprenticed under various anatomists and surgeons until he was appointed as a [https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/lithotomy#medicalDictionary "lithotomist"] at St. Thomas Hospital in London in 1719. His specialization and his operative removal of bladder stones helped revolutionize the field and significantly increase survival rates (>90%). It was cited that he could complete a swift and skillful lithotomy in as little as fifty-four seconds, key before the advancements in anesthesia. In 1727, he developed his own technique of removal of bladder stones by using a lateral perineal incision compared to the standard suprapubic approach. This technique soon gained popularity among surgeons all across Europe. He also gained recognition within ophthalmic surgery for his operation known as an [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iridectomy "iridectomy"] (1728), surgically restoring a blind man's vision by creating an opening that served as an artificial pupil. He later published [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2948710/ "Osteographia"], or the Anatomy of the Bones (1733) which gave a comprehensive description of the human skeletal system <ref name="Neher">, A. (n.d.). The Truth about Our Bones: William Cheselden's Osteographia. National Library of Medicine</ref>. He moved to Chelsea Hospital in 1738 and was appointed chief of surgery. He [https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/historicalanatomies/cheselden_bio.html#:~:text=As%20a%20surgeon%2C%20he%20was,American%20editions%20up%20to%201806. "died"] in Bath, England in 1752 at the age of 63. | [https://www.britannica.com/biography/William-Cheselden "William Cheselden"] (Oct. 19, 1688 - Apr. 10, 1752) was a British surgeon and teacher <ref name="William Cheselden">: British surgeon and teacher. (1998, July 20). Britannica</ref>. He was an important figure in revolutionizing and establishing surgery as a profession within the medical field. Cheselden was elected as a fellow of the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Society "Royal Society"] of London for Improving Natural Knowledge in 1712. It was following this when he was a teacher of anatomy and surgery, highlighted by the publishing of his anatomical atlas Anatomy of the Human Body (1792). He recognized a need for the development of formal anatomy coursework. He studied and was apprenticed under various anatomists and surgeons until he was appointed as a [https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/lithotomy#medicalDictionary "lithotomist"] at St. Thomas Hospital in London in 1719. His specialization and his operative removal of bladder stones helped revolutionize the field and significantly increase survival rates (>90%) <ref name="Cheselden">: Author & Title Description. (n.d.). National Library of Medicine</ref>. It was cited that he could complete a swift and skillful lithotomy in as little as fifty-four seconds, key before the advancements in anesthesia. In 1727, he developed his own technique of removal of bladder stones by using a lateral perineal incision compared to the standard suprapubic approach. This technique soon gained popularity among surgeons all across Europe. He also gained recognition within ophthalmic surgery for his operation known as an [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iridectomy "iridectomy"] (1728), surgically restoring a blind man's vision by creating an opening that served as an artificial pupil. He later published [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2948710/ "Osteographia"], or the Anatomy of the Bones (1733) which gave a comprehensive description of the human skeletal system <ref name="Neher">, A. (n.d.). The Truth about Our Bones: William Cheselden's Osteographia. National Library of Medicine</ref>. He moved to Chelsea Hospital in 1738 and was appointed chief of surgery. He [https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/historicalanatomies/cheselden_bio.html#:~:text=As%20a%20surgeon%2C%20he%20was,American%20editions%20up%20to%201806. "died"] in Bath, England in 1752 at the age of 63. | ||

===Gerard Vandergucht (Van der Gucht)=== | ===Gerard Vandergucht (Van der Gucht)=== | ||

[[File:Gerard-Vandergucht.webp|right|Gerard Vandergucht|300px]] | [[File:Gerard-Vandergucht.webp|right|Gerard Vandergucht|300px]] | ||

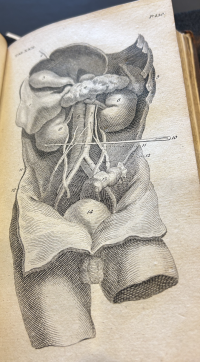

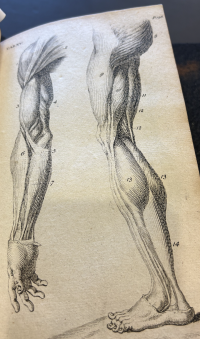

This specific edition of the book is the thirteenth edition, and similar to the other editions, it is highlighted by its forty copper plate engravings done by [https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person/mp10800/gerard-vandergucht "Gerard Vandergucht"] (1696/1697 - March 18, 1776). Gerard Vandergucht was a famous English engraver and art dealer. His family history runs deep in engraving as he was taught by his father Michael Vandergucht. Michael created many engravings of human anatomy, some of which were published in William Cowper’s book Myotomia Reformata. In addition to learning the craft from his father, he was taught by Louis Chéron and studied at the Great Queen Street Academy. Gerard gained popularity in London as an engraver because of his use of a French etching style of blending with pinpoint engraving. Intaglio engraving on a copper plate allows for the ability to engrave what you want in a precise mirror image. This technology was developed around the 1600s and it was very popular in books about anatomy because the engravings combined the benefits of free drawing and etched tonal gradation. Gerard was commissioned by various painters and booksellers until his father’s death when he took over the family business (Golden Head in Queen Street, Bloomsbury). Following his contributions to Cheselden’s Anatomy of the Human Body, he also helped to create engravings for his arguably more famous book Osteographia, or the Anatomy of the Bones. He also made strides by contributing to modern-day copyright law with the Engraving Copyright Act of 1734. He continued his family’s rich history in engraving by having over 30 children, his son Benjamin Vandergucht being the most notable. He later moved to Essex, England where he passed away in 1776. | This specific edition of the book is the thirteenth edition, and similar to the other editions, it is highlighted by its forty copper plate engravings done by [https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/person/mp10800/gerard-vandergucht "Gerard Vandergucht"] (1696/1697 - March 18, 1776). Gerard Vandergucht was a famous English engraver and art dealer. His family history runs deep in engraving as he was taught by his father Michael Vandergucht. Michael created many engravings of human anatomy, some of which were published in William Cowper’s book Myotomia Reformata. In addition to learning the craft from his father, he was taught by Louis Chéron and studied at the Great Queen Street Academy. Gerard gained popularity in London as an engraver because of his use of a French etching style of blending with pinpoint engraving. Intaglio engraving on a copper plate allows for the ability to engrave what you want in a precise mirror image. This technology was developed around the 1600s and it was very popular in books about anatomy because the engravings combined the benefits of free drawing and etched tonal gradation. Gerard was commissioned by various painters and booksellers until his father’s death when he took over the family business (Golden Head in Queen Street, Bloomsbury). Following his contributions to Cheselden’s Anatomy of the Human Body, he also helped to create engravings for his arguably more famous book Osteographia, or the Anatomy of the Bones. He also made strides by contributing to modern-day copyright law with the Engraving Copyright Act of 1734. He continued his family’s rich history in engraving by having over 30 children, his son Benjamin Vandergucht being the most notable. He later moved to Essex, England where he passed away in 1776. | ||

===Significance=== | ===Significance=== | ||

Latest revision as of 03:39, 12 May 2024

Overview

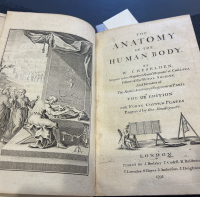

Anatomy of the Human Body by William Cheselden is a medically extensive anatomical atlas that contains various case studies and illustrations. There is countless evidence that suggests that the book’s first edition was printed and published around 1713, but this edition (XIII) was later expanded on and published in the late 18th century, containing further information about muscles, organs, and other structures. It is not a manuscript but rather evidence of using the printing press and moveable type. Interestingly, the copper plate engravings have been inserted later than publication indicated by pages that do not contribute to the running page number. Cheselden decided it would be best to use camera obscura in later novels to create initial drawings for the illustrations and engravings. Cheselden combined his expertise in surgery and anatomy with the need for the creation of a standardized medical textbook and created this book.

History of Anatomical Illustrations: From Renaissance Humanism to Detailed Realism

The style and technique of "anatomical illustrations" speak great volumes about the effectiveness and accuracy associated with them. The anatomical picture books of the Renaissance era and Baroque styling saw the inclusion of woodcuts. This older technology has severe constraints related to accuracy because of the characteristics of the substrates themselves. Also in these older medical textbooks, human nature was portrayed as god-like, and images depicted humans as heroes. A revolutionary time in this field came with the British empirical traditions of the 18th century. William Cheselden was part of this time and was set on assuring detailed realism in portraying the bodies of humans. Detaching the idea of style and an artist’s personal bias can help to ensure uniformity and accuracy throughout books. [1]

Historical Background, Key Figures, and Significance

Historical Context

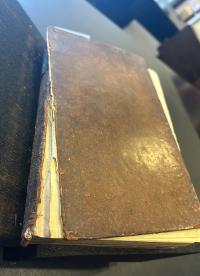

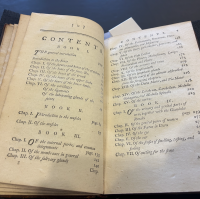

Anatomy of the Human Body (1792) is an anatomical atlas first published in 1712 which ran through thirteen editions up until the 19th century. This text was used as the standard medical textbook for many years, gaining heaps of popularity among medical students. The book was unique because it went against the standard of Latin and was printed in English. The book contains case studies that describe various injuries and how they were treated such as amputations. The text also contains lists of body parts, organs, and bones which are coupled with illustrations which made this work so popular among medical students. For this time, this book served as an organized medical textbook that students would most likely use to study. With the publishing of this book, modern copyright laws established by 1710 gave the printer legal rights. As this book was published in the late 18th century (1792), it follows and is consistent with modern copyright laws of this time period. It is a medium-sized book and follows a typical rectangular shape with a folio page arrangement.

William Cheselden

"William Cheselden" (Oct. 19, 1688 - Apr. 10, 1752) was a British surgeon and teacher [2]. He was an important figure in revolutionizing and establishing surgery as a profession within the medical field. Cheselden was elected as a fellow of the "Royal Society" of London for Improving Natural Knowledge in 1712. It was following this when he was a teacher of anatomy and surgery, highlighted by the publishing of his anatomical atlas Anatomy of the Human Body (1792). He recognized a need for the development of formal anatomy coursework. He studied and was apprenticed under various anatomists and surgeons until he was appointed as a "lithotomist" at St. Thomas Hospital in London in 1719. His specialization and his operative removal of bladder stones helped revolutionize the field and significantly increase survival rates (>90%) [3]. It was cited that he could complete a swift and skillful lithotomy in as little as fifty-four seconds, key before the advancements in anesthesia. In 1727, he developed his own technique of removal of bladder stones by using a lateral perineal incision compared to the standard suprapubic approach. This technique soon gained popularity among surgeons all across Europe. He also gained recognition within ophthalmic surgery for his operation known as an "iridectomy" (1728), surgically restoring a blind man's vision by creating an opening that served as an artificial pupil. He later published "Osteographia", or the Anatomy of the Bones (1733) which gave a comprehensive description of the human skeletal system [4]. He moved to Chelsea Hospital in 1738 and was appointed chief of surgery. He "died" in Bath, England in 1752 at the age of 63.

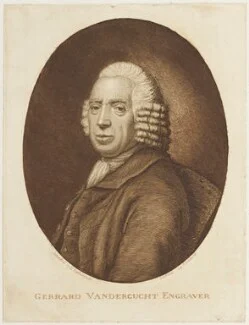

Gerard Vandergucht (Van der Gucht)

This specific edition of the book is the thirteenth edition, and similar to the other editions, it is highlighted by its forty copper plate engravings done by "Gerard Vandergucht" (1696/1697 - March 18, 1776). Gerard Vandergucht was a famous English engraver and art dealer. His family history runs deep in engraving as he was taught by his father Michael Vandergucht. Michael created many engravings of human anatomy, some of which were published in William Cowper’s book Myotomia Reformata. In addition to learning the craft from his father, he was taught by Louis Chéron and studied at the Great Queen Street Academy. Gerard gained popularity in London as an engraver because of his use of a French etching style of blending with pinpoint engraving. Intaglio engraving on a copper plate allows for the ability to engrave what you want in a precise mirror image. This technology was developed around the 1600s and it was very popular in books about anatomy because the engravings combined the benefits of free drawing and etched tonal gradation. Gerard was commissioned by various painters and booksellers until his father’s death when he took over the family business (Golden Head in Queen Street, Bloomsbury). Following his contributions to Cheselden’s Anatomy of the Human Body, he also helped to create engravings for his arguably more famous book Osteographia, or the Anatomy of the Bones. He also made strides by contributing to modern-day copyright law with the Engraving Copyright Act of 1734. He continued his family’s rich history in engraving by having over 30 children, his son Benjamin Vandergucht being the most notable. He later moved to Essex, England where he passed away in 1776.

Significance

In a time that lacked a comprehensive, organized, and readily available medical textbook, this book helped to fix those problems for more than 100 years in the medical field. The unique and precise methodology involved in creating this book allowed readers to enhance their knowledge of various subjects, depicting muscles and tendons with incredible detail. This book ultimately served as a stepping stone and advancement within the development of anatomical atlases. This book's illustrations played a crucial role in advancing anatomical knowledge, were considered some of the best of their time, and helped to set the standard for copper plate engravings to come. In terms of medical advancements, this book helped to greatly progress the understanding of skeletal and organ systems within the human body. This book and the advancements of its author, William Cheselden, revolutionized the medical field and had a great lasting impact.

Material Analysis and Physical Description

Provenance

Limited information is available regarding previous owners of this edition of the book but it does state that The University of Pennsylvania received this book as a donation from "Austin H. Lamont". Upon further research, Lamont was a member of the Perelman School of Medicine at Penn for more than 20 years and played a key role in the development of anesthesiology into a medical discipline. His connection to the medical field makes sense considering the contents of the book. This was also the only book that he has donated to Penn. The catalog also lists the names S. R. Maitland (bookplate) and Henry Novington (autograph). This means that these autographs were found somewhere in this book and the bookplate addresses and corresponds to the other individuals. Specifically, it was printed for J. Dodsley, T Cadwell, R. Baldwin, T. Lowndes, S. Hayes, and J. Anderson. The author also addresses someone named Dr. Richard Mead who is a physician to the king, a fellow of the College of Physicians in London, and a member of the Royal Society. However, given the considerations of how the book was circulated, it is likely that thousands of people came into contact with this book as a method of studying and learning about anatomy.

Marks and Marginalia

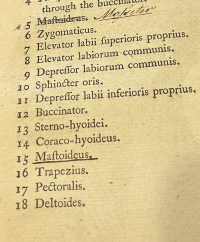

Various marks, annotations, and marginalia are often useful for book historians in determining the readership and circulation of old books such as this one. Various marks are often used for different purposes such as emphasizing something important, correcting something wrong, or anything that helps with the familiarization of the text. This book does not contain many indications of annotations or marginalia. I think in a book of this nature, highlighting would be a mark that would make the most sense because a reader may have highlighted specific information that they found difficult or particularly important. Limited use of annotations tells us that the reader most likely had less knowledge regarding the information that the book discusses and that the information presented in the book is historically and biologically accurate. However, there is one instance that does show some writing that has been done clearly after publication, but it is difficult to determine what is being said and by whom. Additionally, one asemic mark that I will refer to in the book occurs on a page that gives an in depth description of the anatomy of the cheek. This specific mark refers to some underlining. In this case it appears that the term does not match up with the copper engraving. As the engravings were added after the book was published, it seems as though someone went back and crossed off the information that was not referring to the correct body part in the image. It also seems like there was a repeat of the same part as number five and number fifteen both refer to the same part.

Substrate, Format, Binding, Structure, and Illustrations

Considering the book as an object and observing the substrate, the cover appears to be a layer of leather over some type of board, most likely cardboard. There are copper engravings that have been inserted into the book at a later date. As we have previously discussed in class, this is evidence of intaglio engraving on a copper plate. With this method, you can engrave what you want in a mirror image by etching. This technology was developed around the 1600s and was very popular in books about anatomy. The camera obscura concept allows for very precise details which increases the quality and effectiveness of the illustrations. Especially for the images that depict tendons and muscles, this engraving with tonal etching creates revolutionary illustrations. A more accurate image would help a medical student get a better sense of what something actually looks like when he observes a specific body part or organ in real life. Something distinctive about this book is the original binding and the deterioration of the leather layer. When handling the book, it is clear that it is original and is very delicate. When holding the book and placing it on a surface, particles of the covers come off and have a similar color to copper. This is something known as "red rot" which is the degradation of leather most likely caused by high humidity, pollution or high temperatures. Leather is an interesting material to use because of its deterioration over time as well as degradation with extensive use. This book seems to follow contemporary trends of the 18th and 19th century through the use of its substrates and binding. Additionally, the deterioration of the leather and the cover becoming separated from the binding indicates extensive use and how the book was handled. Throughout the 18th century, many bindings began to become more "decorative". There was a resurgence in the use of simple book structure and binding with recessed, support sewing. It is a relatively simple book structure which appears to have some sewing for support. Additionally, Intaglio printing was common and was also utilized in this book. I think the decorations and colors in the binding are very interesting and add a nice pattern to it. I also think it is interesting that the word “Cheselden’s Anatomy” is on the side of the binding in a black and gold color which helps it stand out.

Some mechanisms that this book uses to help the reader navigate the book is the use of an index and table of contents. The text is organized into 3 books and has a running page number throughout the whole book. These are systematic characteristics that help a reader navigate a book and provide proper organization and flow of information. These images illustrate the table of contents and the division of the work into separate parts (books). The use of an index which contains different vocabulary words related to anatomy gives the expectation that the reader would use these words that correspond to images to review and educate themselves. The separation of the book into different sections also tells us about the skills the reader may have. For example, if the reader had a substantial knowledge of information about the heart, they could use these mechanisms to navigate these sections and learn about others.

Bibliography

- ↑ . (n.d.). Style and non-style in anatomical illustration: From Renaissance Humanism to Henry Gray. National Library of Medicine.

- ↑ : British surgeon and teacher. (1998, July 20). Britannica

- ↑ : Author & Title Description. (n.d.). National Library of Medicine

- ↑ , A. (n.d.). The Truth about Our Bones: William Cheselden's Osteographia. National Library of Medicine