A North African Megillat Esther: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (17 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== Overview == | |||

This is a Jewish Megillat Esther (Scroll of Esther), chanted publicly for the holiday of Purim. Though limited information is available, it appears that this scroll was written in North Africa—probably Tunisia—between 1800-1850, and displays signs of heavy use. The scroll is now housed in the University of Pennsylvania's Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts. Its physical condition and quality of the letters now invalidates its use as a Megillah, except for in pressing times.<ref>https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/FRANKLIN_9977569840503681.</ref> [[File:Screenshot 2023-05-01 at 6.26.45 PM.png|300px]] | |||

== Background == | |||

The Scroll of Esther, commonly referred to as “the Megillah,” was written originally in ancient Persia in the 5th century BCE and became part of the “Writings” section of the Hebrew Bible. It recounts the story of a Jewish woman named Esther who marries King Ahaseurus, ruler of Persia, without revealing her Jewish identity. Eventually, when a decree is passed by the King’s advisor calling for the murder of all the Jews in the land, Esther cleverly pits the two against each other. Finally, upon revealing her identity, the decree is canceled, the evil advisor killed, and the Jews saved.<ref>Schellekens, Jona. “Accession Days and Holidays: The Origins of the Jewish Festival of Purim.” Journal of Biblical Literature, vol. 128, no. 1, 2009, pp. 115–34. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/25610170. Accessed 1 May 2023.</ref> The ancient Jewish sages instituted the annual public reading of the Megillah to remind the Jews of the Divine Providence throughout the story.<ref>SEGAL, ELIEZER L. “Esther.” Vol. 2 The Babylonian Esther Midrash: A Critical Commentary, Brown Judaic Studies, 2020, pp. 39–104. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvzpv59d.7. Accessed 1 May 2023.</ref> | The Scroll of Esther, commonly referred to as “the Megillah,” was written originally in ancient Persia in the 5th century BCE and became part of the “Writings” section of the Hebrew Bible. It recounts the story of a Jewish woman named Esther who marries King Ahaseurus, ruler of Persia, without revealing her Jewish identity. Eventually, when a decree is passed by the King’s advisor calling for the murder of all the Jews in the land, Esther cleverly pits the two against each other. Finally, upon revealing her identity, the decree is canceled, the evil advisor killed, and the Jews saved.<ref>Schellekens, Jona. “Accession Days and Holidays: The Origins of the Jewish Festival of Purim.” Journal of Biblical Literature, vol. 128, no. 1, 2009, pp. 115–34. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/25610170. Accessed 1 May 2023.</ref> The ancient Jewish sages instituted the annual public reading of the Megillah to remind the Jews of the Divine Providence throughout the story.<ref>SEGAL, ELIEZER L. “Esther.” Vol. 2 The Babylonian Esther Midrash: A Critical Commentary, Brown Judaic Studies, 2020, pp. 39–104. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvzpv59d.7. Accessed 1 May 2023.</ref> | ||

[[File:Screenshot 2023-05-01 at 6.35.43 PM.png|500px]] | |||

== History of this scroll == | |||

According to the University of Pennsylvania’s Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, this scroll was written between 1800 and 1850, but little else is known. Even how it ended up at the University of Pennsylvania is not public information. However, since Megillah scrolls are fairly common compared to Torah scrolls, it is quite prevalent that museums display them, whereas Torah scrolls are often kept within Jewish organizations, even after becoming invalid. | According to the University of Pennsylvania’s Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, this scroll was written between 1800 and 1850, but little else is known. Even how it ended up at the University of Pennsylvania is not public information. However, since Megillah scrolls are fairly common compared to Torah scrolls, it is quite prevalent that museums display them, whereas Torah scrolls are often kept within Jewish organizations, even after becoming invalid. | ||

== Historical context == | |||

There was a large Jewish community in North Africa throughout history, which started declining in the early-mid 20th century as immigration to the Land of Israel, largely in response to severe antisemitism. It is likely that this scroll was used by a Rabbi or knowledgable layman to be chanted on the Purim holiday in synagogues, or used by a congregant to follow along with the cantor. Another possibility is that this scroll was brought to different places, like hospitals and children’s homes, so those who could not hear the Megillah would be able to. | There was a large Jewish community in North Africa throughout history, which started declining in the early-mid 20th century as immigration to the Land of Israel, largely in response to severe antisemitism. It is likely that this scroll was used by a Rabbi or knowledgable layman to be chanted on the Purim holiday in synagogues, or used by a congregant to follow along with the cantor. Another possibility is that this scroll was brought to different places, like hospitals and children’s homes, so those who could not hear the Megillah would be able to. | ||

== Authorship == | |||

Jewish law dictates that scrolls must be written by pious men who are knowledgeable in the intricacies of writing letters, crowns, and having the proper intention.<ref>Shaarei Teshuvah 691/2; Regarding if it may be written by a woman or child-see Shaarei Teshuvah 691/3; Keses Hasofer 28/3.</ref> | Jewish law dictates that scrolls must be written by pious men who are knowledgeable in the intricacies of writing letters, crowns, and having the proper intention.<ref>Shaarei Teshuvah 691/2; Regarding if it may be written by a woman or child-see Shaarei Teshuvah 691/3; Keses Hasofer 28/3.</ref> | ||

As such, automatic knowledge of these characteristics of the scribe is given. Whether or not he was an ordained rabbi or not is impossible to tell, but there are no obvious signs of the original manuscript being invalid (though it now is) which indicates that the scribe was skilled.<ref>FROJMOVIC, EVA. “THE PERFECT SCRIBE AND AN EARLY ENGRAVED ESTHER SCROLL.” The British Library Journal, vol. 23, no. 1, 1997, pp. 68–80. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42554445. Accessed 1 May 2023.</ref> | As such, automatic knowledge of these characteristics of the scribe is given. Whether or not he was an ordained rabbi or not is impossible to tell, but there are no obvious signs of the original manuscript being invalid (though it now is) which indicates that the scribe was skilled.<ref>FROJMOVIC, EVA. “THE PERFECT SCRIBE AND AN EARLY ENGRAVED ESTHER SCROLL.” The British Library Journal, vol. 23, no. 1, 1997, pp. 68–80. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42554445. Accessed 1 May 2023.</ref> | ||

== Notable features == | |||

The first condition for a valid Megillah is that it is written on parchment, which this Megillah clearly is.<ref>Shulchan Aruch 691/1.</ref> | The first condition for a valid Megillah is that it is written on parchment, which this Megillah clearly is.<ref>Shulchan Aruch 691/1.</ref> | ||

The animal is not clear, but the skin is evident on the back of the parchment where one can see many bumps. | The animal is not clear, but the skin is evident on the back of the parchment where one can see many bumps. | ||

Megillahs but also be written with black ink, as can be seen in the pictures.<ref>Ibid.</ref> | Megillahs but also be written with black ink, as can be seen in the pictures.<ref>Ibid.</ref> | ||

[[File:Screenshot 2023-05-01 at 6.45.19 PM.png|300px]] | |||

The engraved lines in the Megillah are also mandated by Jewish law.<ref>Ibid.</ref> | The engraved lines in the Megillah are also mandated by Jewish law.<ref>Ibid.</ref> | ||

| Line 33: | Line 42: | ||

The margins marking every column are also obligatory, and only in times of need can one use a scroll without these margins.<ref>Shulchan Aruch 691/2.</ref> | The margins marking every column are also obligatory, and only in times of need can one use a scroll without these margins.<ref>Shulchan Aruch 691/2.</ref> | ||

Though many letters are either missing or invisible in this Megillah, this invalidates the scroll only when there is no alternative. However, after the fact, if one read from this Megillah, he and his congregation would have fulfilled their obligation of hearing the Megillah.<ref>Ibid. 690/8; Kaf Hachaim 690/15.</ref> This rule applies only if the majority of the words and letters are intact, as those in this Megillah are.<ref>https://shulchanaruchharav.com/halacha/ | [[File:Screenshot 2023-05-01 at 6.51.05 PM.png|300px]] | ||

Though many letters are either missing or invisible in this Megillah, this invalidates the scroll only when there is no alternative. However, after the fact, if one read from this Megillah, he and his congregation would have fulfilled their obligation of hearing the Megillah.<ref>Ibid. 690/8; Kaf Hachaim 690/15.</ref> This rule applies only if the majority of the words and letters are intact, as those in this Megillah are.<ref>https://shulchanaruchharav.com/halacha/a-kosher-megillah/#_ftn43.</ref> | |||

Finally, there are many laws regarding the sons of Haman and how their names should be written. First, if the names of his sons are not written in the form of a song, the Megillah is invalid.<ref>Shulchan Aruch 691/3.</ref> The accepted custom is to write the names of the ten sons on its own page without any other verses.<ref>Shaar Hatziyon ibid in name of Nishmas Adam on Chayeh Adam 154; Shaar Efraim.</ref> | Finally, there are many laws regarding the sons of Haman and how their names should be written. First, if the names of his sons are not written in the form of a song, the Megillah is invalid.<ref>Shulchan Aruch 691/3.</ref> The accepted custom is to write the names of the ten sons on its own page without any other verses.<ref>Shaar Hatziyon ibid in name of Nishmas Adam on Chayeh Adam 154; Shaar Efraim.</ref> | ||

[[File:Screenshot 2023-05-01 at 6.46.40 PM.png|300px]] | |||

== Signs of use == | |||

The age of this scroll and apparent use has led to a decay in its quality over time. In numerous places certain letters appear to have been scraped off, while tears, holes, and stains appear frequently throughout. In several places it appears that the text has been written over by more recent scribes, indicating that this scroll went through several repairs. | The age of this scroll and apparent use has led to a decay in its quality over time. In numerous places certain letters appear to have been scraped off, while tears, holes, and stains appear frequently throughout. In several places it appears that the text has been written over by more recent scribes, indicating that this scroll went through several repairs. | ||

[[File:IMG 3995.jpeg|300px]] | |||

== End of the scroll == | |||

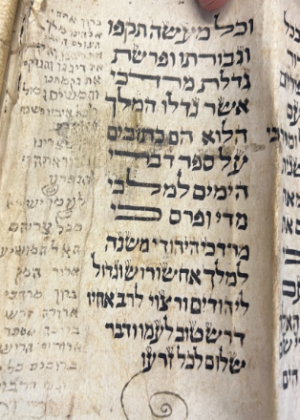

At the end of the Megillah scroll is written an after-blessing on having read the scroll and a piyut (liturgical hymn) beginning with the words Asher Heini. The hymn is traditionally sung in congregations upon concluding the reading of the Megillah, and contains several references to Haman’s sons and to the various miracles performed in the story. It appears that the blessing and song were not written in ink as the rest of the scroll is, but as a separate addition. | At the end of the Megillah scroll is written an after-blessing on having read the scroll and a piyut (liturgical hymn) beginning with the words Asher Heini. The hymn is traditionally sung in congregations upon concluding the reading of the Megillah, and contains several references to Haman’s sons and to the various miracles performed in the story. It appears that the blessing and song were not written in ink as the rest of the scroll is, but as a separate addition. | ||

[[File:Screenshot 2023-05-01 at 6.48.45 PM.png|300px]] | |||

Latest revision as of 15:43, 2 May 2023

Overview

This is a Jewish Megillat Esther (Scroll of Esther), chanted publicly for the holiday of Purim. Though limited information is available, it appears that this scroll was written in North Africa—probably Tunisia—between 1800-1850, and displays signs of heavy use. The scroll is now housed in the University of Pennsylvania's Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts. Its physical condition and quality of the letters now invalidates its use as a Megillah, except for in pressing times.[1]

Background

The Scroll of Esther, commonly referred to as “the Megillah,” was written originally in ancient Persia in the 5th century BCE and became part of the “Writings” section of the Hebrew Bible. It recounts the story of a Jewish woman named Esther who marries King Ahaseurus, ruler of Persia, without revealing her Jewish identity. Eventually, when a decree is passed by the King’s advisor calling for the murder of all the Jews in the land, Esther cleverly pits the two against each other. Finally, upon revealing her identity, the decree is canceled, the evil advisor killed, and the Jews saved.[2] The ancient Jewish sages instituted the annual public reading of the Megillah to remind the Jews of the Divine Providence throughout the story.[3]

History of this scroll

According to the University of Pennsylvania’s Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, this scroll was written between 1800 and 1850, but little else is known. Even how it ended up at the University of Pennsylvania is not public information. However, since Megillah scrolls are fairly common compared to Torah scrolls, it is quite prevalent that museums display them, whereas Torah scrolls are often kept within Jewish organizations, even after becoming invalid.

Historical context

There was a large Jewish community in North Africa throughout history, which started declining in the early-mid 20th century as immigration to the Land of Israel, largely in response to severe antisemitism. It is likely that this scroll was used by a Rabbi or knowledgable layman to be chanted on the Purim holiday in synagogues, or used by a congregant to follow along with the cantor. Another possibility is that this scroll was brought to different places, like hospitals and children’s homes, so those who could not hear the Megillah would be able to.

Authorship

Jewish law dictates that scrolls must be written by pious men who are knowledgeable in the intricacies of writing letters, crowns, and having the proper intention.[4]

As such, automatic knowledge of these characteristics of the scribe is given. Whether or not he was an ordained rabbi or not is impossible to tell, but there are no obvious signs of the original manuscript being invalid (though it now is) which indicates that the scribe was skilled.[5]

Notable features

The first condition for a valid Megillah is that it is written on parchment, which this Megillah clearly is.[6] The animal is not clear, but the skin is evident on the back of the parchment where one can see many bumps. Megillahs but also be written with black ink, as can be seen in the pictures.[7]

The engraved lines in the Megillah are also mandated by Jewish law.[8] Though impossible to know whether this was upheld practically speaking, Jewish law deems any Megillah written without the proper intention of the “sanctity of the Megillah” to be invalid.[9]

The margins marking every column are also obligatory, and only in times of need can one use a scroll without these margins.[10]

Though many letters are either missing or invisible in this Megillah, this invalidates the scroll only when there is no alternative. However, after the fact, if one read from this Megillah, he and his congregation would have fulfilled their obligation of hearing the Megillah.[11] This rule applies only if the majority of the words and letters are intact, as those in this Megillah are.[12]

Finally, there are many laws regarding the sons of Haman and how their names should be written. First, if the names of his sons are not written in the form of a song, the Megillah is invalid.[13] The accepted custom is to write the names of the ten sons on its own page without any other verses.[14]

Signs of use

The age of this scroll and apparent use has led to a decay in its quality over time. In numerous places certain letters appear to have been scraped off, while tears, holes, and stains appear frequently throughout. In several places it appears that the text has been written over by more recent scribes, indicating that this scroll went through several repairs.

End of the scroll

At the end of the Megillah scroll is written an after-blessing on having read the scroll and a piyut (liturgical hymn) beginning with the words Asher Heini. The hymn is traditionally sung in congregations upon concluding the reading of the Megillah, and contains several references to Haman’s sons and to the various miracles performed in the story. It appears that the blessing and song were not written in ink as the rest of the scroll is, but as a separate addition.

- ↑ https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/FRANKLIN_9977569840503681.

- ↑ Schellekens, Jona. “Accession Days and Holidays: The Origins of the Jewish Festival of Purim.” Journal of Biblical Literature, vol. 128, no. 1, 2009, pp. 115–34. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/25610170. Accessed 1 May 2023.

- ↑ SEGAL, ELIEZER L. “Esther.” Vol. 2 The Babylonian Esther Midrash: A Critical Commentary, Brown Judaic Studies, 2020, pp. 39–104. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvzpv59d.7. Accessed 1 May 2023.

- ↑ Shaarei Teshuvah 691/2; Regarding if it may be written by a woman or child-see Shaarei Teshuvah 691/3; Keses Hasofer 28/3.

- ↑ FROJMOVIC, EVA. “THE PERFECT SCRIBE AND AN EARLY ENGRAVED ESTHER SCROLL.” The British Library Journal, vol. 23, no. 1, 1997, pp. 68–80. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42554445. Accessed 1 May 2023.

- ↑ Shulchan Aruch 691/1.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Kol Yaakov 691/12.

- ↑ Shulchan Aruch 691/2.

- ↑ Ibid. 690/8; Kaf Hachaim 690/15.

- ↑ https://shulchanaruchharav.com/halacha/a-kosher-megillah/#_ftn43.

- ↑ Shulchan Aruch 691/3.

- ↑ Shaar Hatziyon ibid in name of Nishmas Adam on Chayeh Adam 154; Shaar Efraim.