Civil War Scrapbook: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

=== Content and Classes of Documents === | === Content and Classes of Documents === | ||

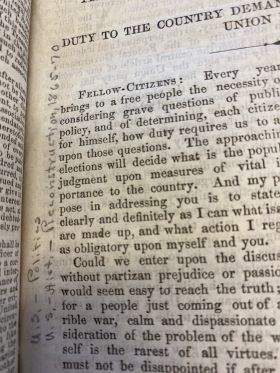

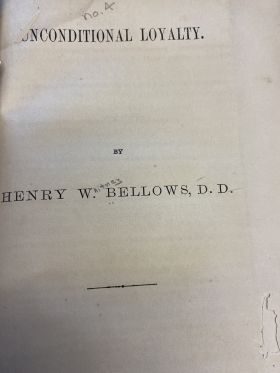

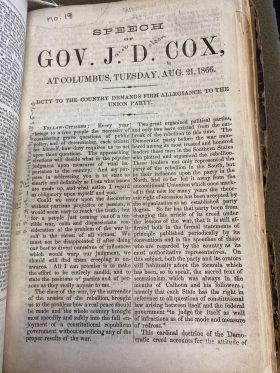

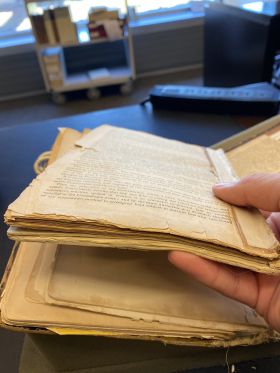

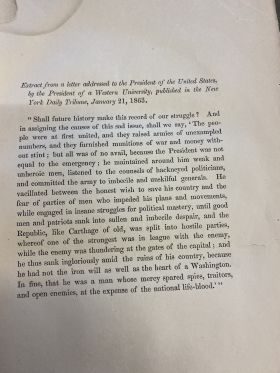

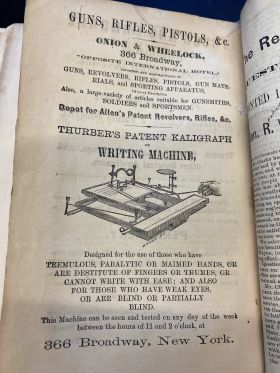

Beyond the physical way in which the documents were collected and combined, the intent of the scrapbook’s creation can be gleaned from the content and order of the documents found within. Most documents fall into three classes: persuasive artifacts, factual artifacts, and cultural artifacts. Documents such as newspaper opinion pieces, speeches to government, letters, and theses fall into the first category; they seem to have been produced primarily for the purpose of arguing for the Northern narrative with regard to the war and fit in most closely with the definition of “propaganda” used by Garvey, although documents shouldn’t necessarily be viewed with the negative connotation that such a word conveys<ref name=":0" />. This class includes the majority of documents in the scrapbook and are found near the beginning. The factual artifacts include material such as financial accounts and battle records, often organized in a style similar to reference texts. Although these documents rarely include an explicit argument for a particular narrative, the ways that information is included, excluded, or organized are largely congruent with the arguments of the persuasive artifacts. For example, a common sentiment captured in Southern scrapbooks was the idea that the North was at risk of bankruptcy; financial documents in Northern scrapbooks, although not directly persuasive, served the purpose of responding to and refuting these Southern claims. Financial reports were also often used to legitimize the establishment of government and non-profit groups during the Civil War, as discussed by Normand and Wootton; the financial evidence used in persuasive arguments by political and social leaders may also have been placed in this scrapbook with the assumption that readers at the time would recall their use and understand the implication of their inclusion<ref>Normand, Carol J, and Charles W Wootton. “Use of Financial Statements to Legitimize a New Non-Profit Organization During the US Civil War: The Case of the Northwestern Sanitary Commission.” Accounting history newsletter. 15.1 (2010): 93–119. Web.</ref>. Finally, cultural artifacts are the least relevant and least common documents, and the purpose for their inclusion is the least clear. These are primarily pamphlets advertising products, such as a Kaligraph, and events, such as trading fairs. These advertisements occur at the end of the scrapbook and may have been added as an afterthought. | |||

[[File:Letter2 civil war.jpg|thumb|280px|left|Letter to President; Published in New York Daily Tribune]] | [[File:Letter2 civil war.jpg|thumb|280px|left|Letter to President; Published in New York Daily Tribune]] | ||

[[File:Ad Kali.jpg|thumb|280px| | [[File:Ad Kali.jpg|thumb|280px|right|Kaligraph Advertisement]] | ||

[[File:Spreadsheet.HEIC.jpg|thumb|280px| | [[File:Spreadsheet.HEIC.jpg|thumb|280px|left|Example of Financial Information Presented as a Spreadsheet]] | ||

=== Inspiration for Creation === | === Inspiration for Creation === | ||

Latest revision as of 14:26, 10 May 2022

This scrapbook contains a several documents published for mass circulation and public consumption in the years surrounding the Civil War. The documents include letters sent to political leaders, speeches made in congress, newspaper articles, and even advertisements. The text was most likely constructed by an individual or a small group (i.e. a family) from the North.

Context

Characteristics of Civil War Scrapbooks

The documents captured in scrapbooks at the time of the Civil War were largely of personal, individual significance. It would be less common for institutions, companies, or other groups to use scrapbooks as a medium for content preservation. Rather, it was content generated by these groups that would often be preserved in scrapbooks by individuals or households with political dispositions matching the sentiment of these texts. Northern and Southern Civil War scrapbooks differed a lot in terms of the content they included content and the story they told about nationhood and abolition. Garvey mentions that the most common materials found in Civil War era scrapbooks include newspapers, poems, and legal documents[1]. However, the concentration of different documents and the forms in which they appear can reveal the area of origin before even looking at their content. Specifically, newspapers were not as well circulated in the South, and thus were less common in scrapbooks put together by confederates. Further, when newspapers were included in Southern scrapbooks, they were usually transcribed by hand, and often paraphrased to exaggerate anti-abolitionist and pro-confederate sentiment. Finally, the timing of a scrapbooks’ creation is often indicative of the sentiment it portrayed. Almost all scrapbooks collected toward the end or after of the Civil War were done so in the South, often in response to the confederates’ loss and in an attempt to tell the version of history Southerners were scared would otherwise be lost, as mentioned by Seed[2]. By contrast, many scrapbooks created early in the Civil War contained arguments for abolition and evidences for the need of Union preservation as well as the lack of necessity of slavery.

Kislak Scrapbook

This scrapbook has many signs clearly indicating northern origin. There are no documents that are primarily transcribed, although many of the printed documents have notes added in the margins. These marks are made in pen and are mostly functional in the scrapbook’s construction or supplementary to the texts. For example, most of the documents at the beginning of the scrapbook have comments at the top of their first page indicating the order in which they should be included (i.e. “No. X”). All other handwritten notes in the scrapbook contextualize documents, for example by spelling out full names or describing why an address to congress was made. Although some documents included are from the end of the war (particularly those describing the impact or chronology of important events), many of the newspaper and court documents are dated before or near the beginning of the Civil War. Further, entire theses describing the importance of abolition are included in this scrapbook; although such theses are not mentioned by Garvey[1], they clearly support a northern, anti-slavery sentiment.

Substrate and Form

Paper

The scrapbook contains artifacts printed with black ink exclusively on paper, such as newspapers and copies of letters. Longer texts include printed transcripts of speeches given to legislators (i.e. the house of representatives) recorded line by line that were almost certainly not original copies; original transcriptions would not have been publicly accessible and would have been preserved much more rigorously than in this scrapbook. Further, the transcriptions were usually modified and included appendices including financial information and other supplementary documents referenced in the event being transcribed. These modifications require afterthought and sometimes post-analysis, whereas original copies of these documents would have been produced at the time of the court event. Thus, most of if not all texts collected in the scrapbook were copies of documents produced for mass distribution and wide consumption. Additionally, the dates on the documents spanned multiple years (1860-1866). These facts combine to imply that the scrapbook’s creator added documents that seemed interesting or supported an argument.

Compilation

The documents were clearly compiled from different sources because the way that pages were attached varied across documents. Some documents used thin string wound through several holes threaded along the spine and others used thicker string ran through three holes slightly distal from the spine, for example. Groups of 3-5 documents were bound together with glue and cloth wrapped around the bundle, and the bundles were attached with glue to a scrapbook cover made of thick corrugated filler board. Garvey mentions that many early scrapbooks had intentionally removable parts. It is hard to determine if the bundles of documents were intentionally removable, or if they became separated from the cover after intense use[1]. The numbering of the documents may be used to reconstruct the scrapbook in the correct order after pieces are removed, but they may also have been used to construct the document in the first place as instructions for the scrapbook’s creator (perhaps from themselves). It seems the second case is more likely, because documents are numbered even within bundles that are not separable.

Means and Timing of Compilation

The timing and intentionality of this scrapbooks’ compilation process is ambiguous. The scrapbook may have been proactive or reactive, and intentional or passive. Firstly, it is possible that the documents were collected proactively, or over time. For example, the book’s creator may have had the intention to compile materials that support the Northern perspective on abolition and nationhood. To do so, they may have attentively monitored documents as they were published included those that fit his goal in the final scrapbook. Alternatively, near the end or even after the war, the creator may have wished to collect documents that captured their personal experience and public sentiment. To further this objective, they may have tracked down previously published articles. Although the latter chronology is possible, this scrapbook’s thoroughness suggests that there would have to have been at least some interest in collecting documents, even if the idea to compile a scrapbook happened later. Alternatively, the scrapbook may have been a joint effort by a small community of family whose members collectively had copies of the documents kept within.

Regardless, the scrapbook was certainly prepared with strong intention. Almost all the documents included within it are the same size. Garvey mentions that scrapbooks often contain “scraps” that are randomly collected and are unlikely to match in shape, scale, or substrate[1]. For example, letters between influential political and social leaders discussing issues of slavery and secession were usually handwritten on thicker types of paper, as mentioned by Bernier[3]. When these letters are included in the scrapbook, however, they are prepared on a type of paper that matched the other documents included in the scrapbook. Thus, intentional preparation was done to either find or reproduce documents in a form that would conveniently be bound to resemble a codex. Thus, this book would have been much easier to construct if done proactively, but certainly would have been possible to create reactively as well. Regardless, the work put into this scrapbook’s construction is much more intentional and thorough than usual.

Content and Organization

Content and Classes of Documents

Beyond the physical way in which the documents were collected and combined, the intent of the scrapbook’s creation can be gleaned from the content and order of the documents found within. Most documents fall into three classes: persuasive artifacts, factual artifacts, and cultural artifacts. Documents such as newspaper opinion pieces, speeches to government, letters, and theses fall into the first category; they seem to have been produced primarily for the purpose of arguing for the Northern narrative with regard to the war and fit in most closely with the definition of “propaganda” used by Garvey, although documents shouldn’t necessarily be viewed with the negative connotation that such a word conveys[1]. This class includes the majority of documents in the scrapbook and are found near the beginning. The factual artifacts include material such as financial accounts and battle records, often organized in a style similar to reference texts. Although these documents rarely include an explicit argument for a particular narrative, the ways that information is included, excluded, or organized are largely congruent with the arguments of the persuasive artifacts. For example, a common sentiment captured in Southern scrapbooks was the idea that the North was at risk of bankruptcy; financial documents in Northern scrapbooks, although not directly persuasive, served the purpose of responding to and refuting these Southern claims. Financial reports were also often used to legitimize the establishment of government and non-profit groups during the Civil War, as discussed by Normand and Wootton; the financial evidence used in persuasive arguments by political and social leaders may also have been placed in this scrapbook with the assumption that readers at the time would recall their use and understand the implication of their inclusion[4]. Finally, cultural artifacts are the least relevant and least common documents, and the purpose for their inclusion is the least clear. These are primarily pamphlets advertising products, such as a Kaligraph, and events, such as trading fairs. These advertisements occur at the end of the scrapbook and may have been added as an afterthought.

Inspiration for Creation

The high concentration of persuasive documents imply that the scrapbook was created to be used as a comprehensive argument in support of the Northern perspective. Alternatively, the author may have collected documents to reaffirm their opinions with public sentiment expressed in widely distributed media. The factual artifacts also focus on large-scale topics such as national financial health or the timeline of the entire war, rather than specific battles. Garvey mentions that the inspiration for many Civil War scrapbooks was the death of a loved one, but the lack of focus on a particular battle or event suggest that the inspiration for this scrapbook was a more general fascination with the ongoing Civil War[1].

However, the factual and cultural artifacts at the end of the scrapbook suggest that the intention for its use changed over the course of the war. Once the persuasive component of the text was completed, the author found it useful to include not only information on the war overall, but also irrelevant material developed at the time of the war. It seems likely that including advertisements served a sentimental purpose and for readers to remember (or understand) what things were being discussed at the time of the war, besides the war itself.

Circulation and Use

General Civil War Scrapbook Uses

Garvey describes that Civil War scrapbooks were rarely used for public circulation and had a much more personal use. Often these scrapbooks would only be looked by their original author, but they were also often shared with friends, community members, or collogues[1]. The practice of comparative scrapbooking was common, in which documents within or across scrapbooks would be analyzed to understand differences in accounts and sentiment. Not surprisingly, in the late 1800s this was almost never done with scrapbooks with different origins (i.e. the north and south), even though such a comparison would reveal the greatest contrast.

Intended Use

The meticulous way in which documents were bound together to ensure consistency in size, shape, and material while creating a clean look when all items were combined indicates that the creator had some intention of using this scrapbook for external facing purposes. Scrapbooks that were only meant for personal use were much more likely to have scraps that varied in format and shape and had a much less professional appearance. Further, the state of the scrapbook is indicative of heavy use; the pages are clearly worn, and many have stains from oil, water, or other ambiguous substances. The binding, which is very strong and built from string, cloth, and glue, is also broken in several locations, implying regular use.

The scrapbook was also packaged in a thick, wooden carrying case; it is possible that this was added much later than when the scrapbook was created, because other civil war scrapbooks in the Kislak collection didn’t have similar cases. If the case was added by a collector prior to the scrapbooks’ arrival in Kislak, the original scrapbook may have been difficult to send across long distances and was likely used primarily within a particular community. However, if the author used the case themselves, it may have been intended as a container to make it easier to send across long distances. If this was the case, the scrapbook may have been sent to different communities or scholarly organizations to review the sentiments and events of the war.

Sources

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Gruber Garvey, Ellen. Writing with Scissors : American Scrapbooks from the Civil War to the Harlem Renaissance /. Oxford ; New York :: Oxford University Press,, 2013. Web.

- ↑ Seed, David. Life and Limb : Perspectives on the American Civil War. Liverpool :: Liverpool University Press,, 2017. Print.

- ↑ Bernier, Celeste-Marie, Judie Newman, and Matthew Pethers. The Edinburgh Companion to Nineteenth-Century American Letters and Letter-Writing /. Edinburgh :: Edinburgh University Press,, 2016. Print.

- ↑ Normand, Carol J, and Charles W Wootton. “Use of Financial Statements to Legitimize a New Non-Profit Organization During the US Civil War: The Case of the Northwestern Sanitary Commission.” Accounting history newsletter. 15.1 (2010): 93–119. Web.