Grimm's Goblins Illustrated: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (15 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

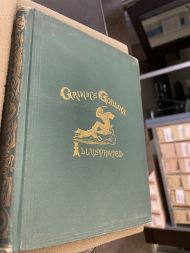

''Grimm’s Goblins Illustrated'' is a collection of [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grimms%27_Fairy_Tales Grimms’ fairy tales] that have been translated into English. It consists of thirteen fairy tales | [[File:Grimm's Goblins Book Cover.jpeg|230px|thumb|right|The front cover of ''Grimm's Goblins Illustrated''.]] | ||

''Grimm’s Goblins Illustrated'' is a collection of [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grimms%27_Fairy_Tales Grimms’ fairy tales] that have been translated into English. It consists of thirteen fairy tales and 7 color illustrations. The book was released in 1867 by [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ticknor_and_Fields Ticknor and Fields], a Boston-based group that dominated the publishing industry in the nineteenth century. It is currently stored in the Rare Book Collection of the [https://www.library.upenn.edu/kislak Kislak Center for Special Collections] at the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/University_of_Pennsylvania University of Pennsylvania], where it resides under the shelf mark [https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/FRANKLIN_9948062413503681 PT921.G6 G75 1867]. | |||

=Background= | =Background= | ||

===The Tales' Origins: Who Were The Brothers Grimm, and What Were Their Stories=== | ===The Tales' Origins: Who Were The Brothers Grimm, and What Were Their Stories=== | ||

From 1810 to 1857, the Grimms collected, transcribed, transliterated, and edited the words of German | [[File:GrimmBrothers.jpeg|150px|thumb|right|A 1855 painting by [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elisabeth_Jerichau-Baumann Elisabeth Jerichau-Baumann] depicting Wilhelm (left) and Jacob (right) Grimm''.]] | ||

Born in the 1780s, [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brothers_Grimm Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm] grew up in Germany at a time of intra-country dissension and disunity.<ref name="vibrant">Zipes, Jack. “The Vibrant Body of the Grimms' Folk and Fairy Tales, Which Do Not Belong to the Grimms." In ''Grimm Legacies: The Magic Spell of the Grimms' Folk and Fairy Tales'', 1-32. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017.</ref> From 1810 to 1857, the Grimms collected, transcribed, transliterated, and edited the words of German folktales they were sent or told. In compiling these tales, the brothers’ primary intention was to instill Germany’s people with a stronger sense of connection to their country.<ref name="american">Zipes, Jack. "Americanization of the Grimms' Folk and Fairy Tales: Twists and Turns of History." In ''Grimm Legacies: The Magic Spell of the Grimms' Folk and Fairy Tales'', 78-108. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017.</ref> In fact, when the brothers first published their tales, they did not even envision children as their main audience; rather, their intended readership was adult German scholars.<ref name="vibrant" /> They hoped that by salvaging these soon-to-be-forgotten German folk stories, they could create a pop culture that was uniquely rooted in German beliefs and customs, thereby unifying the Germanic people under one nation-state. | |||

In the tales' original German form, they contain narratives characterized by cruel punishment, grotesque violence, and religious discrimination.<ref name="american"/> However, overtime, as the tales began to permeate book markets outside of Germany, they were adapted to suit other cultures through the translation process. Ultimately, the tales made their way to Europe and America, where they underwent their greatest transformation. | |||

===Fairy Tale Fever: How, Why, and When the Tales Began To Take Over Nineteenth Century Children's Literature=== | ===Fairy Tale Fever: How, Why, and When the Tales Began To Take Over Nineteenth Century Children's Literature=== | ||

The reason that Grimms’ fairy tales are so widespread today can be attributed first to their | The reason that Grimms’ fairy tales are so widespread today can be attributed first to their [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anglicisation anglicization], and then to their [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Americanization Americanization]. The tales were first translated into English by British translators in the 1820s, where they were shaped by translators’ intended audience– English bourgeois families.<ref name="american"/> In channeling an ideal of British sensibility, translators removed the tales of acts such as incest, child abuse, and grotesque violence. The tales were also made more family-friendly through the inclusion of illustrations. | ||

With so much literary activity occurring in England, various | With so much literary activity occurring in England, various anglicized versions of these tales began to trickle into the American book market in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The editions that best saturated the market during this time were those that pandered to children and captured their attention.<ref name="american"/> Many editions were able to accomplish this by including more imagery and illustrations in their books– for example, by the time the century ended, a large number of the American versions of the tales were often published individually in [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toy_book “toy” books] and [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Picture_book picture books]. Americans saw fairy tales as a mechanism to teach morality and altruism to American children in a light-hearted, innocent manner.<ref name="american"/> As such, other publishers were able to establish themselves within the children's literature market by following in England’s footsteps, and further sanitizing the tales. It is within this timeframe that ''Grimm’s Goblins Illustrated'' exists. | ||

= | =''Grimm's Goblins Illustrated'''s Place Within Children's Literature= | ||

===Illustrations=== | ===Illustrations=== | ||

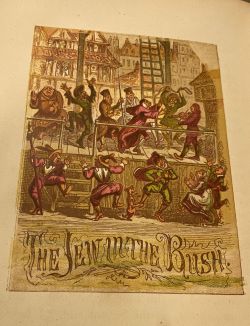

Seven of the book’s tales begin with color illustrations of the tales’ most pivotal scenes. | [[File:JewinBush.jpg|250px|thumb|left| Cruikshank's illustration of ''The Jew in the Bush''. The men's facial expressions are clearly not depicted accurately, and are instead caricaturist and entertaining.]] | ||

The illustrations were printed via chromoxylography, a color woodblock printing process. This technique requires printers to reproduce images by carving out different areas of different woodblocks, each of which is coated in a different color of ink. To allow for variation in tone and a greater spectrum of color, these blocks are often hatched with lines. After the paper is pressed against each engraved block, the process yields a colored illustration. | Seven of the book’s tales begin with color illustrations of the tales’ most pivotal scenes. Plot-based illustrations were fairly common in Ticknor and Fields’ children’s books at this time– they were thought to appeal to younger audiences by making the works more vivid, thereby strengthening children’s connections to the stories.<ref name="Winship">Winship, Michael. ''American Literary Publishing in the Mid-nineteenth Century: The Business of Ticknor and Fields''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995. </ref> The illustrations were produced by [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Cruikshank George Cruikshank], a British [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caricature caricaturist] who was well-known for his fun and engaging art. Cruikshank’s illustration style enables the book to appeal to a younger audience– characters are drawn with overly expressive facial expressions, and in oddly contortionist body positions. These illustrations further enshrine the book within the realm of juvenile literature. Grimms’ fairy tales are known for their dark undertones and violence. However, the inherent scariness of the fairy tales is alleviated in the face of Cruikshank’s comedic depictions. In this way, the book is further able to appeal to children. | ||

This book contains various signs of the use of chromoxylography– each illustration contains stipple from hatching, and each illustrated page is embossed on its backside. It is not surprising that Ticknor and Fields utilized the printing technique here. Chromoxylography was one of the most popular forms of illustrative printing during the nineteenth century, particularly in the | The illustrations were printed via [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chromoxylography chromoxylography], a color [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Woodblock_printing woodblock printing] process. This technique requires printers to reproduce images by carving out different areas of different woodblocks, each of which is coated in a different color of ink.<ref name="Bamber">Gascoigne, Bamber. ''How to Identify Prints: A Complete Guide to Manual and Mechanical Processes from Woodcut to Inkjet : with 272 Illustrations, 40 in Colour''. 2nd ed. London: Thames and Hudson, 2004.</ref> To allow for variation in tone and a greater spectrum of color, these blocks are often [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hatching hatched] with lines. After the paper is pressed against each engraved block, the process yields a colored illustration. | ||

This book contains various signs of the use of chromoxylography– each illustration contains stipple from hatching, and each illustrated page is embossed on its backside. It is not surprising that Ticknor and Fields utilized the printing technique here. Chromoxylography was one of the most popular forms of illustrative printing during the nineteenth century, particularly in children’s literature, because the children's book market was consistently plagued with lower profit margins.<ref name="Ray">Ray, Gordon Norton. ''The Illustrator and the Book in England from 1790 to 1914''. Rev. ed. New York: Courier, 1991.</ref> Through crosshatching, printers could essentially mix colors, and therefore could rely on fewer ink colors to create vividly colored images.<ref name="Bamber"/> Thus, in publishing this book, Ticknor and Fields were able to balance being economical with being child-friendly. | |||

===External Features=== | ===External Features=== | ||

The book contains various other decorative elements that pander to a juvenile audience. The book’s cover and spine are both gold-stamped | [[File:CoverSpine.jpg|190px|thumb|right| A clear demonstration of the gold-stamping on ''Grimm's Goblins Illustrated'''s cover and spine.]] | ||

The book contains various other decorative elements that pander to a juvenile audience. The book’s cover and spine are both gold-stamped and printed with imagery. While including gold-stamped wording and illustrative vignettes was a fairly customary practice for Ticknor and Fields’ juvenile literature, it was less common for them to use gold-stamping on the book cover too.<ref name="Winship"/> Given the historical context, it is clear that Ticknor and Fields published their book in this way in an effort to garner children’s attention. As the fairy tales were not quite popularized yet in America, the publishers knew that they had to draw children to the book in other, flashier ways. While they likely hoped that Cruikshank's illustrations would hold children’s interest as they perused the book, the gold-stamping would be the catalyst that captured children’s attention in the first place. | |||

===Content=== | ===Content=== | ||

The book contains thirteen translated versions of Grimms’ tales: The Presents of the Little Folk, The Little Elves, The Almond-Tree, The Fox’s Brush, The Evil Spirit and His Grandmother, The Wonderful Musician, The Dwarfs, Rumpelstiltskin, Florinda and Florindel, The Jew Among the Thorns, The Three Little Men in the Wood, The Golden Goose, and The King of the Golden Mountain. Having reviewed both | The book contains thirteen translated versions of Grimms’ tales: ''The Presents of the Little Folk'', [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Elves_and_the_Shoemaker ''The Little Elves''], [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Juniper_Tree_(fairy_tale) ''The Almond-Tree''], ''The Fox’s Brush'', [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Devil_and_his_Grandmother ''The Evil Spirit and His Grandmother''], [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Wonderful_Musician ''The Wonderful Musician''], ''The Dwarfs'', [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rumpelstiltskin ''Rumpelstiltskin''], [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jorinde_and_Joringel ''Florinda and Florindel''], [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Jew_Among_Thorns ''The Jew Among the Thorns''], [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Three_Little_Men_in_the_Wood ''The Three Little Men in the Wood''], [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Golden_Goose ''The Golden Goose''], and [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_King_of_the_Golden_Mountain ''The King of the Golden Mountain'']. Having reviewed both anglicized versions of the tales as well as more literal synopses of Grimms’ fairy tales, it is clear that Ticknor and Fields’ translation of the tales does not shy away from grotesqueness and violence. For example, in many stories– such as ''The Almond-Tree''– themes of child abuse and brutal dismemberment persist. This is a clear deviation from the aforementioned cultural shift that was occurring in the children’s literature space around the time that this book was published. By turning our attention to signs of how readers interacted with this book, we can shed some light on how the selected translations could have impacted this book's readership. | ||

[[File:SignOfUse.jpg|180px|thumb|right|A photo showing pages 16 and 17 of Grimm's Goblins Illustrated. The twine binding the pages together has loosened, and pages are falling out, suggesting that this section of the book was quite well-read.]] | |||

===Signs of Book Use=== | ===Signs of Book Use=== | ||

The book’s early pages show various signs of usage– the pages are marred with rips and stains, and many of the threads binding the pages together are split. However, later in the book, there are fewer signs of | The book’s early pages show various signs of usage– the pages are marred with rips and stains, and many of the threads binding the pages together are split. However, later in the book, there are fewer signs of book usage– the book’s binding is stable, and its pages are perfectly clean. The contrast between the signs of reader usage in the earlier and latter sections of the book suggests that the book was not read in its totality often. This assumption is further supported in light of the book’s material attributes and the previously established historical context. | ||

=== | ===A Synthesis of the Information at Hand=== | ||

While the book’s gold-stamped external features might have been enough to attract the attention of children, they were likely not enough to maintain their attention. The | While the book’s gold-stamped external features might have been enough to attract the attention of children, they were likely not enough to maintain their attention. The book itself is very text-heavy. While illustrations are included in the book, there are very few, at a rate of less than one per tale. Moreover, as mentioned earlier, the compilations of fairy tales that tended to gain prominence during this time period were those with sanitized plotlines.<ref name="american"/> As such, this book’s more literal translation of Grimms’ tales could have disturbed children and their families, thereby compelling readers to put away the book prematurely. | ||

=How ''Grimm's Goblins Illustrated'' Fits Into the Greater Historical Context= | =How ''Grimm's Goblins Illustrated'' Fits Into the Greater Historical Context= | ||

This book occupies a unique niche in the timeline governing the evolution of children’s literature. The second half of the nineteenth century is a time when publishers of American children’s literature began to favor publishing shorter, purified fairy tales that were dominated by the inclusion of pictures.<ref name="american"/> This book, published in 1867, is indicative of this trend, but does not fully embrace it. The inclusion of illustrations alongside the tales is emblematic of the publishing trend towards entertaining and delighting children. However, the lack of sanitization in the tales’ translations demonstrates how gradual the process governing the tales' transformation was. This was not a sudden movement within the children’s literature space; rather, Grimms’ fairy tales underwent a series of shifts overtime that ultimately appropriated the tales for children’s consumption. | |||

Later on, as | Later on, as American renditions of Grimms’ fairy tales became increasingly saccharine and children-centric, they began to dominate the catalogs of media conglomerates like [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Walt_Disney_Company Disney]. Today, it is the Americanized versions of Grimms’ tales that society knows and loves– not the original German versions. This book serves as a real-life case study for the anglicization and Americanization processes that transformed Grimms’ fairy tales into what they are today. | ||

Latest revision as of 22:58, 4 May 2022

Grimm’s Goblins Illustrated is a collection of Grimms’ fairy tales that have been translated into English. It consists of thirteen fairy tales and 7 color illustrations. The book was released in 1867 by Ticknor and Fields, a Boston-based group that dominated the publishing industry in the nineteenth century. It is currently stored in the Rare Book Collection of the Kislak Center for Special Collections at the University of Pennsylvania, where it resides under the shelf mark PT921.G6 G75 1867.

Background

The Tales' Origins: Who Were The Brothers Grimm, and What Were Their Stories

Born in the 1780s, Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm grew up in Germany at a time of intra-country dissension and disunity.[1] From 1810 to 1857, the Grimms collected, transcribed, transliterated, and edited the words of German folktales they were sent or told. In compiling these tales, the brothers’ primary intention was to instill Germany’s people with a stronger sense of connection to their country.[2] In fact, when the brothers first published their tales, they did not even envision children as their main audience; rather, their intended readership was adult German scholars.[1] They hoped that by salvaging these soon-to-be-forgotten German folk stories, they could create a pop culture that was uniquely rooted in German beliefs and customs, thereby unifying the Germanic people under one nation-state. In the tales' original German form, they contain narratives characterized by cruel punishment, grotesque violence, and religious discrimination.[2] However, overtime, as the tales began to permeate book markets outside of Germany, they were adapted to suit other cultures through the translation process. Ultimately, the tales made their way to Europe and America, where they underwent their greatest transformation.

Fairy Tale Fever: How, Why, and When the Tales Began To Take Over Nineteenth Century Children's Literature

The reason that Grimms’ fairy tales are so widespread today can be attributed first to their anglicization, and then to their Americanization. The tales were first translated into English by British translators in the 1820s, where they were shaped by translators’ intended audience– English bourgeois families.[2] In channeling an ideal of British sensibility, translators removed the tales of acts such as incest, child abuse, and grotesque violence. The tales were also made more family-friendly through the inclusion of illustrations. With so much literary activity occurring in England, various anglicized versions of these tales began to trickle into the American book market in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The editions that best saturated the market during this time were those that pandered to children and captured their attention.[2] Many editions were able to accomplish this by including more imagery and illustrations in their books– for example, by the time the century ended, a large number of the American versions of the tales were often published individually in “toy” books and picture books. Americans saw fairy tales as a mechanism to teach morality and altruism to American children in a light-hearted, innocent manner.[2] As such, other publishers were able to establish themselves within the children's literature market by following in England’s footsteps, and further sanitizing the tales. It is within this timeframe that Grimm’s Goblins Illustrated exists.

Grimm's Goblins Illustrated's Place Within Children's Literature

Illustrations

Seven of the book’s tales begin with color illustrations of the tales’ most pivotal scenes. Plot-based illustrations were fairly common in Ticknor and Fields’ children’s books at this time– they were thought to appeal to younger audiences by making the works more vivid, thereby strengthening children’s connections to the stories.[3] The illustrations were produced by George Cruikshank, a British caricaturist who was well-known for his fun and engaging art. Cruikshank’s illustration style enables the book to appeal to a younger audience– characters are drawn with overly expressive facial expressions, and in oddly contortionist body positions. These illustrations further enshrine the book within the realm of juvenile literature. Grimms’ fairy tales are known for their dark undertones and violence. However, the inherent scariness of the fairy tales is alleviated in the face of Cruikshank’s comedic depictions. In this way, the book is further able to appeal to children. The illustrations were printed via chromoxylography, a color woodblock printing process. This technique requires printers to reproduce images by carving out different areas of different woodblocks, each of which is coated in a different color of ink.[4] To allow for variation in tone and a greater spectrum of color, these blocks are often hatched with lines. After the paper is pressed against each engraved block, the process yields a colored illustration. This book contains various signs of the use of chromoxylography– each illustration contains stipple from hatching, and each illustrated page is embossed on its backside. It is not surprising that Ticknor and Fields utilized the printing technique here. Chromoxylography was one of the most popular forms of illustrative printing during the nineteenth century, particularly in children’s literature, because the children's book market was consistently plagued with lower profit margins.[5] Through crosshatching, printers could essentially mix colors, and therefore could rely on fewer ink colors to create vividly colored images.[4] Thus, in publishing this book, Ticknor and Fields were able to balance being economical with being child-friendly.

External Features

The book contains various other decorative elements that pander to a juvenile audience. The book’s cover and spine are both gold-stamped and printed with imagery. While including gold-stamped wording and illustrative vignettes was a fairly customary practice for Ticknor and Fields’ juvenile literature, it was less common for them to use gold-stamping on the book cover too.[3] Given the historical context, it is clear that Ticknor and Fields published their book in this way in an effort to garner children’s attention. As the fairy tales were not quite popularized yet in America, the publishers knew that they had to draw children to the book in other, flashier ways. While they likely hoped that Cruikshank's illustrations would hold children’s interest as they perused the book, the gold-stamping would be the catalyst that captured children’s attention in the first place.

Content

The book contains thirteen translated versions of Grimms’ tales: The Presents of the Little Folk, The Little Elves, The Almond-Tree, The Fox’s Brush, The Evil Spirit and His Grandmother, The Wonderful Musician, The Dwarfs, Rumpelstiltskin, Florinda and Florindel, The Jew Among the Thorns, The Three Little Men in the Wood, The Golden Goose, and The King of the Golden Mountain. Having reviewed both anglicized versions of the tales as well as more literal synopses of Grimms’ fairy tales, it is clear that Ticknor and Fields’ translation of the tales does not shy away from grotesqueness and violence. For example, in many stories– such as The Almond-Tree– themes of child abuse and brutal dismemberment persist. This is a clear deviation from the aforementioned cultural shift that was occurring in the children’s literature space around the time that this book was published. By turning our attention to signs of how readers interacted with this book, we can shed some light on how the selected translations could have impacted this book's readership.

Signs of Book Use

The book’s early pages show various signs of usage– the pages are marred with rips and stains, and many of the threads binding the pages together are split. However, later in the book, there are fewer signs of book usage– the book’s binding is stable, and its pages are perfectly clean. The contrast between the signs of reader usage in the earlier and latter sections of the book suggests that the book was not read in its totality often. This assumption is further supported in light of the book’s material attributes and the previously established historical context.

A Synthesis of the Information at Hand

While the book’s gold-stamped external features might have been enough to attract the attention of children, they were likely not enough to maintain their attention. The book itself is very text-heavy. While illustrations are included in the book, there are very few, at a rate of less than one per tale. Moreover, as mentioned earlier, the compilations of fairy tales that tended to gain prominence during this time period were those with sanitized plotlines.[2] As such, this book’s more literal translation of Grimms’ tales could have disturbed children and their families, thereby compelling readers to put away the book prematurely.

How Grimm's Goblins Illustrated Fits Into the Greater Historical Context

This book occupies a unique niche in the timeline governing the evolution of children’s literature. The second half of the nineteenth century is a time when publishers of American children’s literature began to favor publishing shorter, purified fairy tales that were dominated by the inclusion of pictures.[2] This book, published in 1867, is indicative of this trend, but does not fully embrace it. The inclusion of illustrations alongside the tales is emblematic of the publishing trend towards entertaining and delighting children. However, the lack of sanitization in the tales’ translations demonstrates how gradual the process governing the tales' transformation was. This was not a sudden movement within the children’s literature space; rather, Grimms’ fairy tales underwent a series of shifts overtime that ultimately appropriated the tales for children’s consumption. Later on, as American renditions of Grimms’ fairy tales became increasingly saccharine and children-centric, they began to dominate the catalogs of media conglomerates like Disney. Today, it is the Americanized versions of Grimms’ tales that society knows and loves– not the original German versions. This book serves as a real-life case study for the anglicization and Americanization processes that transformed Grimms’ fairy tales into what they are today.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Zipes, Jack. “The Vibrant Body of the Grimms' Folk and Fairy Tales, Which Do Not Belong to the Grimms." In Grimm Legacies: The Magic Spell of the Grimms' Folk and Fairy Tales, 1-32. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Zipes, Jack. "Americanization of the Grimms' Folk and Fairy Tales: Twists and Turns of History." In Grimm Legacies: The Magic Spell of the Grimms' Folk and Fairy Tales, 78-108. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2017.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Winship, Michael. American Literary Publishing in the Mid-nineteenth Century: The Business of Ticknor and Fields. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Gascoigne, Bamber. How to Identify Prints: A Complete Guide to Manual and Mechanical Processes from Woodcut to Inkjet : with 272 Illustrations, 40 in Colour. 2nd ed. London: Thames and Hudson, 2004.

- ↑ Ray, Gordon Norton. The Illustrator and the Book in England from 1790 to 1914. Rev. ed. New York: Courier, 1991.