The History of Tom Thumb: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (6 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Tom Thumb initial view.jpg|thumb|right|200px|''The history of Tom Thumb'' as found in the Kislak Center.]] | |||

==Introduction== | ==Introduction== | ||

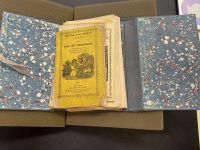

Checking out [https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/FRANKLIN_9959126953503681 The history of Tom Thumb] found in the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/University_of_Pennsylvania University of Pennsylvania]’s [https://www.library.upenn.edu/kislak Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts], not only is one presented with the classic British fairytale, but rather, they are presented with a large collection of early children’s literature dating all the way back to the early 19th century. Upon giving one’s name at Kislak, the staff will not deliver the type of simple little picture book that one flips through as a child | Checking out [https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/FRANKLIN_9959126953503681 ''The history of Tom Thumb''] found in the [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/University_of_Pennsylvania University of Pennsylvania]’s [https://www.library.upenn.edu/kislak Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts], not only is one presented with the classic British fairytale, but rather, they are presented with a large collection of early children’s literature dating all the way back to the early 19th century. Upon giving one’s name at Kislak, the staff will not deliver the type of simple little picture book that one flips through as a child; instead, they will present a codex-appearing box with a weathered and embellished spine that reads “History of Tom Thumb” and “Dialogue Between Two Country Lovers” in gold. | ||

Containing 22 early reader chapter books and toy books, The history of Tom Thumb goes beyond the three-part story and contains a variety of early picture books that | Containing 22 early reader chapter books and toy books, ''The history of Tom Thumb'' goes beyond the three-part story and contains a variety of early picture books that highlight children’s literature of the 19th century. Each of them is no more than 24 pages and have the ability to fit in the palm of one’s hand, demonstrating how both their content and physical material were designed for their audience: children. | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| Line 9: | Line 11: | ||

===Toy books=== | ===Toy books=== | ||

During the 19th century, publishers of children’s picture books | During the 19th century, publishers of children’s picture books soon began to label their works as “toy books” for their nature of being sold alongside candy and stationary sets in general stores as according to book historian at the Kislak center, [https://www.library.upenn.edu/people/staff/john-pollack John Pollack]. Because while chapter and pictures books were utilized to encourage early childhood education and reading, for both book historians and child readers themselves, the picture book served an important role in as an object itself. According to English and children’s literature professor at Indiana University Northwest, [https://www.iun.edu/faculty/george-bodmer/index.htm George Bodmer], he describes the physical properties of the toy book as the following: | ||

<blockquote>“It's something to be held, sniffed, tasted, and enjoyed. It's a toy, an object to bring amusement. In the case of pop-up books, or shaped or textured books, for instance, this objective nature is literally true. It's hardware.”</blockquote> | <blockquote>“It's something to be held, sniffed, tasted, and enjoyed. It's a toy, an object to bring amusement. In the case of pop-up books, or shaped or textured books, for instance, this objective nature is literally true. It's hardware.<ref> Bodmer, George R. "Workbooks and Toybooks: The Task and the Gift of a Child's Book." ''Children's Literature Association Quarterly'' 24, no. 3 (1999): 137</ref>. ”</blockquote> | ||

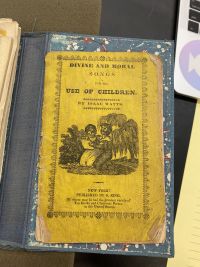

Additionally, | Additionally, Britain dominated the realm of children’s literature<ref>Bold, Melanie Ramdarshan. "Leading the Way: Women-Led Small Presses of Inclusive Youth Literature." ''In The Contemporary Small Press'', edited by Georgina Colby, Kaja Marczewska, and Leigh Wilson, 174. London: Springer Nature, 2020.</ref>, demonstrating the presence of London being listed as the publication city for many of the toy books. The series of 16 toy books were also published directly from Otley Publishing Company, a publishing and stationary company that operated in Hanover Square from 1826-1834. This influence of the toy book soon spread to America as one of the books featured in the Tom Thumb collection, ''Divine and Moral Songs for the Use of Children'', was published in New York City and followed similar toy book publishing practices in terms of paper material, size, and imaging. | ||

===The Story of Tom Thumb=== | ===The Story of Tom Thumb=== | ||

| Line 28: | Line 30: | ||

===The Book Container=== | ===The Book Container=== | ||

[[File:Codex Container Spine.jpg|thumb|left|200px|The spine of ''The history of Tom Thumb''.]] To contain all the various toy books, a container was constructed to house them all. When arriving to the Kislak Center, those who request The history of Tom Thumb are given a book cloth covered book with a leather spine that read “History of Tom Thumb” and “Dialogue Between Two Country Lovers” in gold embellished text. The container highly resembles a traditional codex in appearance and feel, but while the box itself looked like a book, it was not one itself as it lacked bound pages or real content. Rather, the initial container resembles a cardboard binder in a light blue book cloth and is tied together with a matching-colored ribbon. As noted by John Pollack, book cloth was highly utilized in the 19th century as it was invented during the 1820s. Both the leather and cardboard showed signs of temporal wear and tear, which can be justified by the Kislak Center citing the works being published sometime around 1840. This choice for a book cloth covered codex-like container also can be attributed to the nature of the toy books themselves since they are all extremely fragile and allowed for easy transport of children; it is symbolic of a children’s toy chest. | [[File:Codex Container Spine.jpg|thumb|left|200px|The spine of ''The history of Tom Thumb''.]] To contain all the various toy books, a container was constructed to house them all. When arriving to the Kislak Center, those who request The history of Tom Thumb are given a book cloth covered book with a leather spine that read “History of Tom Thumb” and “Dialogue Between Two Country Lovers” in gold embellished text. The container highly resembles a traditional codex in appearance and feel, but while the box itself looked like a book, it was not one itself as it lacked bound pages or real content. Rather, the initial container resembles a cardboard binder in a light blue book cloth and is tied together with a matching-colored ribbon. As noted by John Pollack, book cloth[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bookbinding#cite_ref-22] was highly utilized in the 19th century as it was invented during the 1820s. Both the leather and cardboard showed signs of temporal wear and tear, which can be justified by the Kislak Center citing the works being published sometime around 1840. This choice for a book cloth covered codex-like container also can be attributed to the nature of the toy books themselves since they are all extremely fragile and allowed for easy transport of children; it is symbolic of a children’s toy chest. | ||

===Early Chapter and Toy Book Binding=== | ===Early Chapter and Toy Book Binding=== | ||

While there are a variety of toy books found within the collection, one common trend found within these published works are the physical material that they are printed on. Looking at the texture of the pages, it is evident that each of the books were published on laid paper as demonstrated by its signature parallel, ribbed texture. This use of laid paper coincides with its popularity in English printmaking up until the 19th century until it was replaced by wove paper. Each of the books is also bound together by strands of twine, representing an added element of fragility because while there is little to no marginalia to be discovered, the undoing of the twine binding and rips in laid paper represent reader usage. Since these toy books were meant for children, the simplicity of paper and binding represents its appeal to it audience as they were cheap to produce and an ability to be able to engage with the book as an object without worrying about major damage. | While there are a variety of toy books found within the collection, one common trend found within these published works are the physical material that they are printed on. Looking at the texture of the pages, it is evident that each of the books were published on [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Laid_paper laid paper] as demonstrated by its signature parallel, ribbed texture. This use of laid paper coincides with its popularity in English printmaking up until the 19th century until it was replaced by [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wove_paper wove paper]. Each of the books is also bound together by strands of twine, representing an added element of fragility because while there is little to no marginalia to be discovered, the undoing of the twine binding and rips in laid paper represent reader usage. Since these toy books were meant for children, the simplicity of paper and binding represents its appeal to it audience as they were cheap to produce and an ability to be able to engage with the book as an object without worrying about major damage. | ||

[[File:Tom Thumb Collection.jpg|thumb|right|200px|The full collection of ''The history of Tom Thumb''.]] | [[File:Tom Thumb Collection.jpg|thumb|right|200px|The full collection of ''The history of Tom Thumb''.]] | ||

| Line 42: | Line 44: | ||

Serving at the titular works of the collection, The history of Tom Thumb contains three bound laid paper books that contain woodcut illustrations of the classic British folklore character. The story is thus split into three parts and highlights various aspects from the folklore telling of Tom Thumb. The first part includes a story of Tom Thumb going on an adventure around Britain and ends up becoming swallowed by a cow; the trilogy concludes with Tom meeting King Arthur and the knights of the Round Table. The stories are also written in ABAB rhythmic, demonstrating another appeal to younger audiences who would either be able to get the joy of reading the rhymes themselves or hearing them aloud as they are read to. | Serving at the titular works of the collection, The history of Tom Thumb contains three bound laid paper books that contain woodcut illustrations of the classic British folklore character. The story is thus split into three parts and highlights various aspects from the folklore telling of Tom Thumb. The first part includes a story of Tom Thumb going on an adventure around Britain and ends up becoming swallowed by a cow; the trilogy concludes with Tom meeting King Arthur and the knights of the Round Table. The stories are also written in ABAB rhythmic, demonstrating another appeal to younger audiences who would either be able to get the joy of reading the rhymes themselves or hearing them aloud as they are read to. | ||

What is most interesting about this collection, though, is that despite there being a variety of different toy books, it can be inferred that some of them were printed by the same bookmaker. Guy, Earl of Warwick is an additional toy book present alongside the various Otley chapter books and issues of Tom Thumb. While there is no explicit mention as to where some of the toy books were published such as Guy of Warwick and Tom Thumb, an examination of the illustrations found within them demonstrate that they were most likely published by the same bookmaker or publishing company. Both toy books of Tom Thumb and Guy of Warwick demonstrate similar publishing patterns, being printed on the same type of laid paper, and tied together by similar twine. What is most evident about them sharing publishing house, though, is that they share the exact same woodcut illustrations. One such example is the mirrored image of a man on a horse riding a horse in a field. While some bookmakers would mimic some woodcut illustrations, an in-depth examination of these pictures reveal that the stories most likely shared the same woodblock as denoted by the exact curvature of the horses tail in both and the matching slopes of the background. | [[File:Woodblock images of horse.jpg|thumb|left|200px|Side by side woodcut illustrations from ''Guy of Warwick'' and ''Tom Thumb'' demonstrate exact images of each other.]] What is most interesting about this collection, though, is that despite there being a variety of different toy books, it can be inferred that some of them were printed by the same bookmaker. Guy, Earl of Warwick is an additional toy book present alongside the various Otley chapter books and issues of Tom Thumb. While there is no explicit mention as to where some of the toy books were published such as Guy of Warwick and Tom Thumb, an examination of the illustrations found within them demonstrate that they were most likely published by the same bookmaker or publishing company. Both toy books of Tom Thumb and Guy of Warwick demonstrate similar publishing patterns, being printed on the same type of laid paper, and tied together by similar twine. What is most evident about them sharing publishing house, though, is that they share the exact same woodcut illustrations. One such example is the mirrored image of a man on a horse riding a horse in a field. While some bookmakers would mimic some woodcut illustrations, an in-depth examination of these pictures reveal that the stories most likely shared the same woodblock as denoted by the exact curvature of the horses tail in both and the matching slopes of the background. | ||

===''Otley Chapter Toy Books''=== | ===''Otley Chapter Toy Books''=== | ||

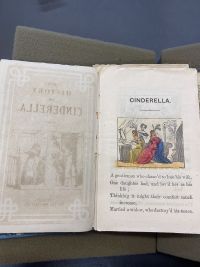

Much like the Tom Thumb series, the Otley toy book series contains 16 different stories printed on laid paper with woodblock illustrations. However, upon flipping through both sets of stories, there is a clear distinction between the two toy book collections: Otley’s inclusion of pochoir illustrations. Each page includes an illustration followed by the story being written in an AABB rhythmic pattern, but rather than the images remaining in black and white, the pages alternate between colored and uncolored images. Looking at the way these images are shaded, it is evident that they were hand-colored with ink as the colors go beyond the lines of the illustrations and resemble simple brush strokes of singular colors. This coloring by hand method is what is known as pochoir, and by utilizing the pochoir coloring, it justifies the alternating colored and non-colored images as using ink on every single page would cause the paper to become subject to ripping or bleeding. Similarly, the choice to utilize pochoir images represent the continuity of simplicity rather than fine detailed choices. Because the audience is children, they most likely appreciated any inclusion of color, so Otley was able to easier coloring methods that also allowed for easier mass publishing. | Much like the Tom Thumb series, the Otley toy book series contains 16 different stories printed on laid paper with woodblock illustrations. However, upon flipping through both sets of stories, there is a clear distinction between the two toy book collections: Otley’s inclusion of [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stencil#cite_ref-dp_6-0 pochoir illustrations]. Each page includes an illustration followed by the story being written in an AABB rhythmic pattern, but rather than the images remaining in black and white, the pages alternate between colored and uncolored images. Looking at the way these images are shaded, it is evident that they were hand-colored with ink as the colors go beyond the lines of the illustrations and resemble simple brush strokes of singular colors. This coloring by hand method is what is known as pochoir, and by utilizing the pochoir coloring, it justifies the alternating colored and non-colored images as using ink on every single page would cause the paper to become subject to ripping or bleeding. Similarly, the choice to utilize pochoir images represent the continuity of simplicity rather than fine detailed choices. Because the audience is children, they most likely appreciated any inclusion of color, so Otley was able to easier coloring methods that also allowed for easier mass publishing. | ||

Additionally, the stories themselves also resemble their appeal to children’s audiences through the subject matter themselves. Each story is a classic children’s fairytale that range from Tom Thumb to Cinderella and Little Red Riding Hood. What stands out about these stories, however, is that some cover pages are printed in red ink, while others are in black ink. This varying of printing choices represents the potential mass production of these stories and the ability to curate one’s own personal collection of all 16 stories. The full list of works included in the Otley chapter book collection are as followed: | Additionally, the stories themselves also resemble their appeal to children’s audiences through the subject matter themselves. Each story is a classic children’s fairytale that range from Tom Thumb to Cinderella and Little Red Riding Hood. What stands out about these stories, however, is that some cover pages are printed in red ink, while others are in black ink. This varying of printing choices represents the potential mass production of these stories and the ability to curate one’s own personal collection of all 16 stories. The full list of works included in the Otley chapter book collection are as followed: | ||

| Line 70: | Line 72: | ||

===''Divine and Moral Songs''=== | ===''Divine and Moral Songs''=== | ||

[[File:Divine and Moral Songs.jpg|thumb|left|200px|The cover of Isaac Watts' ''Divine and Moral Songs for the Use of Children''.]] The first books that appears in ''The history of Tom Thumb'' is actually not one of a London origin, but rather American. The work of ''Divine and Moral Songs for Children'' was written by [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isaac_Watts Issac Watts]. While Watts is an English-borne hymnwriter, the back and front covers demonstrate that the work was published on S. King, 148 Fulton-street, New York, meaning the work was brought to America. This spread of knowledge reflects the intense social, economic, and political pressures that produced a concentration of radical authors and educators in London around 1800 who then contributed to the clustering of a similarly radical and talented group in New York.<ref>Paul, Lissa. ''The Children's Book Business : Lessons from the Long Eighteenth Century''. London: Taylor & Francis Group, 2011: 21</ref> Thus, similarities not only present themselves between English and American children's literature in terms of material aspects, but content as well as Watts' work being published in New York represents the indoctrination of British ideals. | |||

==Significance to Book History== | ==Significance to Book History== | ||

''The history of Tom Thumb'' is much more than just the history of the infamous British folklore – it’s a glimpse into the past and the canon of 19th century children’s literature in terms of publishing and public consumption. Children’s literature was a field that grew in publishing popularity during the 19th century, but it was not necessarily one that was designed with the purpose of education. As stated by Hannah Field from the University of Sussex, children’s literature writers imagined the “child’s ideal physical, rather than intellectual, engagement with a book.” These books were quite literally what they were advertised as: toys. | ''The history of Tom Thumb'' is much more than just the history of the infamous British folklore – it’s a glimpse into the past and the canon of 19th century children’s literature in terms of publishing and public consumption. Children’s literature was a field that grew in publishing popularity during the 19th century, but it was not necessarily one that was designed with the purpose of education. As stated by Hannah Field from the University of Sussex, children’s literature writers imagined the “child’s ideal physical, rather than intellectual, engagement with a book<ref>Field, Hannah. ''Playing with the Book: Victorian Movable Picture Books and the Child Reader''. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019: 29</ref>.” These books were quite literally what they were advertised as: toys. | ||

Additionally, Bodmer comments on the societal impact of the toy book, and more importantly, the act of giving and receiving them: | Additionally, Bodmer comments on the societal impact of the toy book, and more importantly, the act of giving and receiving them: | ||

<blockquote>“The children's book can be seen as a bridge between work and play, between adult and child, between giver and receiver… In return for a gift such as a book, a child is expected to return gratitude, to read, to learn, to value it in an obvious way. Though we want children to appreciate books and reading, we must admit that when we give a child a book, we expect something in return. He or she is beholden to us. It is the peculiar nature of children's books, which Rose describes, that there is a separation between the intended audience and the adult, between consumer and supplier. The gift reinforces the power structure of old and young in our society.”</blockquote> | <blockquote>“The children's book can be seen as a bridge between work and play, between adult and child, between giver and receiver… In return for a gift such as a book, a child is expected to return gratitude, to read, to learn, to value it in an obvious way. Though we want children to appreciate books and reading, we must admit that when we give a child a book, we expect something in return. He or she is beholden to us. It is the peculiar nature of children's books, which Rose describes, that there is a separation between the intended audience and the adult, between consumer and supplier. The gift reinforces the power structure of old and young in our society<ref>Bodmer, George R. "Workbooks and Toybooks: The Task and the Gift of a Child's Book." ''Children's Literature Association Quarterly'' 24, no. 3 (1999): 137</ref>.”</blockquote> | ||

Therefore, the toy book solidifies the idea of the book as on object, serving purposed to place books in the hands of children for the purpose of entertainment and pleasure rather than education and literacy. They were mass produced, cheap, and easily accessible to early readers in both London and the United States as demonstrated by the bookmaking patterns of each toy book in the collection, allowing for childhood fun on the go right in the back of one’s pocket. | Therefore, the toy book solidifies the idea of the book as on object, serving purposed to place books in the hands of children for the purpose of entertainment and pleasure rather than education and literacy. They were mass produced, cheap, and easily accessible to early readers in both London and the United States as demonstrated by the bookmaking patterns of each toy book in the collection, allowing for childhood fun on the go right in the back of one’s pocket. | ||

| Line 83: | Line 87: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

<references /> | |||

Latest revision as of 21:20, 4 May 2022

Introduction

Checking out The history of Tom Thumb found in the University of Pennsylvania’s Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts, not only is one presented with the classic British fairytale, but rather, they are presented with a large collection of early children’s literature dating all the way back to the early 19th century. Upon giving one’s name at Kislak, the staff will not deliver the type of simple little picture book that one flips through as a child; instead, they will present a codex-appearing box with a weathered and embellished spine that reads “History of Tom Thumb” and “Dialogue Between Two Country Lovers” in gold.

Containing 22 early reader chapter books and toy books, The history of Tom Thumb goes beyond the three-part story and contains a variety of early picture books that highlight children’s literature of the 19th century. Each of them is no more than 24 pages and have the ability to fit in the palm of one’s hand, demonstrating how both their content and physical material were designed for their audience: children.

History

Toy books

During the 19th century, publishers of children’s picture books soon began to label their works as “toy books” for their nature of being sold alongside candy and stationary sets in general stores as according to book historian at the Kislak center, John Pollack. Because while chapter and pictures books were utilized to encourage early childhood education and reading, for both book historians and child readers themselves, the picture book served an important role in as an object itself. According to English and children’s literature professor at Indiana University Northwest, George Bodmer, he describes the physical properties of the toy book as the following:

“It's something to be held, sniffed, tasted, and enjoyed. It's a toy, an object to bring amusement. In the case of pop-up books, or shaped or textured books, for instance, this objective nature is literally true. It's hardware.[1]. ”

Additionally, Britain dominated the realm of children’s literature[2], demonstrating the presence of London being listed as the publication city for many of the toy books. The series of 16 toy books were also published directly from Otley Publishing Company, a publishing and stationary company that operated in Hanover Square from 1826-1834. This influence of the toy book soon spread to America as one of the books featured in the Tom Thumb collection, Divine and Moral Songs for the Use of Children, was published in New York City and followed similar toy book publishing practices in terms of paper material, size, and imaging.

The Story of Tom Thumb

The story of Tom Thumb is a classic example of British folklore, an authorless story that continues to be told for centuries and printed in a variety of ways. Captured in three parts, the story highlights a little boy by the titular name who gets into adventures and mischief, whether it’s meeting King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table or accidentally being swallowed by a cow. Though the story of Tom Thumb remains author-less, it became one of the first fairy tale published in English and its first copy can be dated all the way to 1621. This lack of authorship also allowed for freedom of creative expression since there was no author copyright, which explains the different styles of publishing for the story of Tom Thumb. While the traditional story of Tom Thumb is published in three parts and can be seen through the three separate toy books, Otley publishing company produced a completely different style of story, utilizing colored images as well as compiling all three parts into one condensed. In the true nature of folklore, Tom Thumb represents how one story can be interpreted in multiple different ways, both in terms of content and form.

Material Analysis

The Book Container

To contain all the various toy books, a container was constructed to house them all. When arriving to the Kislak Center, those who request The history of Tom Thumb are given a book cloth covered book with a leather spine that read “History of Tom Thumb” and “Dialogue Between Two Country Lovers” in gold embellished text. The container highly resembles a traditional codex in appearance and feel, but while the box itself looked like a book, it was not one itself as it lacked bound pages or real content. Rather, the initial container resembles a cardboard binder in a light blue book cloth and is tied together with a matching-colored ribbon. As noted by John Pollack, book cloth[1] was highly utilized in the 19th century as it was invented during the 1820s. Both the leather and cardboard showed signs of temporal wear and tear, which can be justified by the Kislak Center citing the works being published sometime around 1840. This choice for a book cloth covered codex-like container also can be attributed to the nature of the toy books themselves since they are all extremely fragile and allowed for easy transport of children; it is symbolic of a children’s toy chest.

Early Chapter and Toy Book Binding

While there are a variety of toy books found within the collection, one common trend found within these published works are the physical material that they are printed on. Looking at the texture of the pages, it is evident that each of the books were published on laid paper as demonstrated by its signature parallel, ribbed texture. This use of laid paper coincides with its popularity in English printmaking up until the 19th century until it was replaced by wove paper. Each of the books is also bound together by strands of twine, representing an added element of fragility because while there is little to no marginalia to be discovered, the undoing of the twine binding and rips in laid paper represent reader usage. Since these toy books were meant for children, the simplicity of paper and binding represents its appeal to it audience as they were cheap to produce and an ability to be able to engage with the book as an object without worrying about major damage.

Content

The History of Tom Thumb

Serving at the titular works of the collection, The history of Tom Thumb contains three bound laid paper books that contain woodcut illustrations of the classic British folklore character. The story is thus split into three parts and highlights various aspects from the folklore telling of Tom Thumb. The first part includes a story of Tom Thumb going on an adventure around Britain and ends up becoming swallowed by a cow; the trilogy concludes with Tom meeting King Arthur and the knights of the Round Table. The stories are also written in ABAB rhythmic, demonstrating another appeal to younger audiences who would either be able to get the joy of reading the rhymes themselves or hearing them aloud as they are read to.

What is most interesting about this collection, though, is that despite there being a variety of different toy books, it can be inferred that some of them were printed by the same bookmaker. Guy, Earl of Warwick is an additional toy book present alongside the various Otley chapter books and issues of Tom Thumb. While there is no explicit mention as to where some of the toy books were published such as Guy of Warwick and Tom Thumb, an examination of the illustrations found within them demonstrate that they were most likely published by the same bookmaker or publishing company. Both toy books of Tom Thumb and Guy of Warwick demonstrate similar publishing patterns, being printed on the same type of laid paper, and tied together by similar twine. What is most evident about them sharing publishing house, though, is that they share the exact same woodcut illustrations. One such example is the mirrored image of a man on a horse riding a horse in a field. While some bookmakers would mimic some woodcut illustrations, an in-depth examination of these pictures reveal that the stories most likely shared the same woodblock as denoted by the exact curvature of the horses tail in both and the matching slopes of the background.

Otley Chapter Toy Books

Much like the Tom Thumb series, the Otley toy book series contains 16 different stories printed on laid paper with woodblock illustrations. However, upon flipping through both sets of stories, there is a clear distinction between the two toy book collections: Otley’s inclusion of pochoir illustrations. Each page includes an illustration followed by the story being written in an AABB rhythmic pattern, but rather than the images remaining in black and white, the pages alternate between colored and uncolored images. Looking at the way these images are shaded, it is evident that they were hand-colored with ink as the colors go beyond the lines of the illustrations and resemble simple brush strokes of singular colors. This coloring by hand method is what is known as pochoir, and by utilizing the pochoir coloring, it justifies the alternating colored and non-colored images as using ink on every single page would cause the paper to become subject to ripping or bleeding. Similarly, the choice to utilize pochoir images represent the continuity of simplicity rather than fine detailed choices. Because the audience is children, they most likely appreciated any inclusion of color, so Otley was able to easier coloring methods that also allowed for easier mass publishing.

Additionally, the stories themselves also resemble their appeal to children’s audiences through the subject matter themselves. Each story is a classic children’s fairytale that range from Tom Thumb to Cinderella and Little Red Riding Hood. What stands out about these stories, however, is that some cover pages are printed in red ink, while others are in black ink. This varying of printing choices represents the potential mass production of these stories and the ability to curate one’s own personal collection of all 16 stories. The full list of works included in the Otley chapter book collection are as followed:

- The History of Cinderella

- The History of Tom Thumb

- Hare and many Friends

- Entertaining Views

- Robinson Crusoe

- Jack the Giant Killer

- Little Red Riding Hood

- Scenes from Nature

- Dame Trot

- Mother Hubbard

- Capitals of Europe

- The House that Jack Built

- Death & Burial of Cock Robin

- Cock Robin and Jenny Wren

- Old Man and his Ass

- Peter Brown

Divine and Moral Songs

The first books that appears in The history of Tom Thumb is actually not one of a London origin, but rather American. The work of Divine and Moral Songs for Children was written by Issac Watts. While Watts is an English-borne hymnwriter, the back and front covers demonstrate that the work was published on S. King, 148 Fulton-street, New York, meaning the work was brought to America. This spread of knowledge reflects the intense social, economic, and political pressures that produced a concentration of radical authors and educators in London around 1800 who then contributed to the clustering of a similarly radical and talented group in New York.[3] Thus, similarities not only present themselves between English and American children's literature in terms of material aspects, but content as well as Watts' work being published in New York represents the indoctrination of British ideals.

Significance to Book History

The history of Tom Thumb is much more than just the history of the infamous British folklore – it’s a glimpse into the past and the canon of 19th century children’s literature in terms of publishing and public consumption. Children’s literature was a field that grew in publishing popularity during the 19th century, but it was not necessarily one that was designed with the purpose of education. As stated by Hannah Field from the University of Sussex, children’s literature writers imagined the “child’s ideal physical, rather than intellectual, engagement with a book[4].” These books were quite literally what they were advertised as: toys.

Additionally, Bodmer comments on the societal impact of the toy book, and more importantly, the act of giving and receiving them:

“The children's book can be seen as a bridge between work and play, between adult and child, between giver and receiver… In return for a gift such as a book, a child is expected to return gratitude, to read, to learn, to value it in an obvious way. Though we want children to appreciate books and reading, we must admit that when we give a child a book, we expect something in return. He or she is beholden to us. It is the peculiar nature of children's books, which Rose describes, that there is a separation between the intended audience and the adult, between consumer and supplier. The gift reinforces the power structure of old and young in our society[5].”

Therefore, the toy book solidifies the idea of the book as on object, serving purposed to place books in the hands of children for the purpose of entertainment and pleasure rather than education and literacy. They were mass produced, cheap, and easily accessible to early readers in both London and the United States as demonstrated by the bookmaking patterns of each toy book in the collection, allowing for childhood fun on the go right in the back of one’s pocket.

References

- ↑ Bodmer, George R. "Workbooks and Toybooks: The Task and the Gift of a Child's Book." Children's Literature Association Quarterly 24, no. 3 (1999): 137

- ↑ Bold, Melanie Ramdarshan. "Leading the Way: Women-Led Small Presses of Inclusive Youth Literature." In The Contemporary Small Press, edited by Georgina Colby, Kaja Marczewska, and Leigh Wilson, 174. London: Springer Nature, 2020.

- ↑ Paul, Lissa. The Children's Book Business : Lessons from the Long Eighteenth Century. London: Taylor & Francis Group, 2011: 21

- ↑ Field, Hannah. Playing with the Book: Victorian Movable Picture Books and the Child Reader. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019: 29

- ↑ Bodmer, George R. "Workbooks and Toybooks: The Task and the Gift of a Child's Book." Children's Literature Association Quarterly 24, no. 3 (1999): 137