Home Economics Foods and Food Preparation: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (59 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

''Home Economics Foods and Food Preparation'' is a series of cooking class leaflets created by the School District of Philadelphia. The book was used in a [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Home_economics Home Economics] | [https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/FRANKLIN_9946759163503681 ''Home Economics Foods and Food Preparation''] is a series of cooking class leaflets created by the School District of Philadelphia. It is available at the Kislak Center for Special Collections at [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/University_of_Pennsylvania The University of Pennsylvania]. The book was used in a [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Home_economics Home Economics] course in Philadelphia Public School and was published in 1942. It contains recipes and instructions for cleaning, caring, and cooking. While the textbook itself is generic and mass produced, this particular copy was owned by a female student, Edith Fineberg, and contains her unique notes, recipes, and doodles within the pages and on the covers. The book is full of her personality and becomes a beautiful view into the past. It shows how young girls were taught to be members of society and the expectations placed on them from a young age. | ||

[[File:IMG_0317.jpg|thumb|200px|Front Cover]] | |||

=Background= | =Background= | ||

===Home Economics=== | ===Home Economics=== | ||

[https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Home_economics Home Economics] originated in the early 1900s as part of a movement aimed at preparing young women for professional jobs by equipping them with basic skills like cooking, cleaning, and home care. The course was created as a form of science.<ref>Elias, Megan J. Stir It Up: Home Economics in American Culture. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.</ref> Female students wore lab coats and were taught necessary skills that could help them procure a wide range of jobs for their future. It was created to help women gain independence as part of the liberal feminist movement of the early 1900s.<ref>Elias, Megan J. Stir It Up: Home Economics in American Culture. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.</ref> [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bureau_of_Home_Economics The Federal Bureau of Home Economics] was erected around the same time. The government organization helped teach women during the first world war how to cook with the limited food supplies, had an advice radio show, published recipes, and taught lessons on food and nutrition.<ref>Parkin, Katherine J. Food Is Love: Advertising and Gender Roles in Modern America. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.</ref> There was a focus in American culture that the home could contribute to social change. Managing a properly fed and cared for nuclear family was a way in which young women could have a powerful impact on the future of the country.<ref>Parkin, Katherine J. Food Is Love: Advertising and Gender Roles in Modern America. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.</ref> But in the 1950s there was a major shift in the feminist movement that highlighted how the current structure was a conformist and repressive culture. The home economics field became a primary example for feminists in the 1960s of sexist, inhibitory culture. In response to the backlash the field is no longer studied or taught. | |||

===Chef Fritz Blank=== | |||

The textbook was donated to the Penn Library in 2008 by Chef Fritz Blank, in the largest donation of cookbooks the library has received. Chef Fritz owned a famous restaurant in Philadelphia called Deux Cheminees, one of the first high-end restaurants in Philadelphia. It was opened in 1979 and it brought classic French style cooking to the growing Philadelphia restaurant scene. [[File:Fritz_0.jpg|thumb|200px|Chef Fritz Blank]] | |||

The restaurant was located in two conjoined townhouses decorated to feel cozy and homey. The restaurant was full of bookcases of Chef Fritz's extensive cookbook collection. This particular cookbook stands out, as Chef Fritz was very interested in teaching children. He would go to Philadelphia schools and run cooking classes. Though the book appears to be very generic, as there are thousands of copies of this specific textbook. This one is special for its marginalia and the history behind it. | |||

=The Textbook= | |||

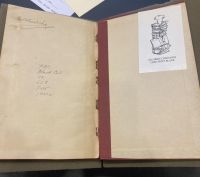

[[File:unnamed.jpg|200px|thumb|The back page of ''Home Economics Foods and Food Preparation''. Staples bind the pages together. The back cover is falling off.]] | |||

===Structure=== | ===Structure=== | ||

''Home Economics Foods and Food Preparation'' was bound by W. Newkirk. Indented into the front cover is “BOUND BY W. NEWKIRK 186 W. NEDRO AVE. PHILA, PA." After extensive research, information on W. Newkirk was hard to come by. Though the address listed on the cover, 186 W. Nedro Ave, was home to the [https://www.ancestry.com/1940-census/usa/Pennsylvania/Dorothy-Newkirk_s69vx Newkirk family in the 1940s.] Any more information on Newkirk is inconclusive. It's possible that he exclusively ran a book binding business, or maybe he bound books in addition to working other jobs. The book itself is bound for durability. There are three thick staples holding together the pages, almost like a pamphlet. The staples are holding just about the maximum amount of pages they can while maintaining the integrity of the book. The book is a series of leaflets. There is no pagination which could mean that the leaflets were printed separately and put together after printing.<ref>Stewart, A. A. The Printer's Dictionary of Technical Terms: a Handbook of Definitions and Information About Processes of Printing; with a Brief Glossary of Terms Used In Book Binding. Boston, Mass.: School of Printing, North End Union, 1912.</ref> The back cover is close to falling off while the front cover and each page is still fully in tact. The front and back cover are likely sturdy cardboard able to endure years of being shoved into book bags, held by children and worn down. These textbooks were designed for practical, functional use by a schoolchild, they were not designed for leisure reading. The books are not beautiful, and they are certainly not expensive. There is nothing elegant about the binding, it is simply functional. The textbooks were produced as cheaply as possible. Nothing could be more generic than these government issued textbooks. | |||

=== | ===Content=== | ||

The book is broken up into 40 separate sections. The sections are laid out on the first page of the book in green-colored text—one of the only two pages with color in the book. There is no title page, just an index with each leaflet section title and number. The first eleven sections are labeled A-L while the subsequent 29 are labeled 1-29. Sections A-L include titles such as “Housekeeping Practice,” “Cleaning Practice,” and “Baby Care.” These sections are quite informative and give a clear set of rules for those to follow. For example, in “Food for the Sick,” there are lists of appropriate foods and their best preparations, a “rules for serving” section, and a seemingly never-ending list of cooking do’s and don’ts. The format is largely based on strict rules, instructions that are clear and easy to follow. The textbook is full of commands rather than recommendations. Textbook lines include: “Avoid discussing food in the presence of the patient and do not ask the patient what she wants.” This textbook approached Home Economics similar to how a mathematics textbook functions. The rules were definitive, leaving little room for creativity. This reflects a way in which the Philadelphia public school system was teaching all of their courses—focused heavily on yes or no answers and memorization rather than creativity. This home economics textbook is an example of the form of education being taught to students in the 1940s. | |||

<gallery mode="packed" perrow=2 heights=250px> | |||

File:IMG_0223.jpeg|Index | |||

File:IMG_0225.jpeg|"Food for the Sick" | |||

</gallery> | |||

The numbered sections are recipes. The organization of the recipes is a bit peculiar. It begins with basics, breads, and breakfasts but scatters other sections like “cereal” and “cake” in seemingly random sections of the book. The recipes are very simple and easy to follow. This textbook was probably made for middle school students considering the simplicity of the recipes.<ref>Perkins, Wilma Lord. The Fannie Farmer junior cook book. Boston, USA. Little, Brown and Company. 1942.</ref> It is a starting point for cooking and teaches many basics that one can carry with them. | |||

===Edith Fineberg=== | |||

There are a number of scribbles and notes in the book. Most notably, the front inside cover has the name Edith Fineberg and her address 5810 Rodman St. Philadelphia, PA. The name and address is written twice. Underneath her name, Edith wrote “Edith loves him” and scribbled a little note to herself that section 10 has sugar cookies. Edith lived in [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/West_Philadelphia West Philly] in the 1940s, a predominantly Jewish neighborhood in Philadelphia at the time.<ref>Joselit, Jenna Weissman, and Murray Friedman. “Jewish Life in Philadelphia, 1830-1940.” The Journal of American History., vol. 72, no. 3, Associated Publishers of American Records, 1985.</ref> | |||

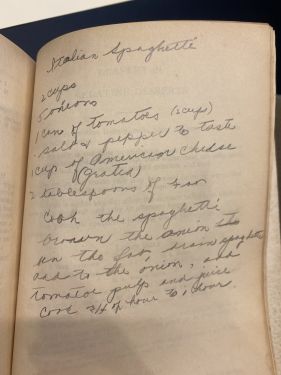

Other sparks of Edith’s personality shine through the book. She scribbled-in-pencil her own recipe in her own added-in chapter, number “29 ½”—for “Italian Spaghetti." There is another recipe for “Hamburg Stew” and one for “Peach Short Cake.” These recipes don’t appear elsewhere in the book. Maybe they were taught to her by her teacher or maybe she had assignments to bring in or create her own recipes. On the back of leaflet 5, Vegetables, you can see her notes from an activity in class or a homework assignment. Edith organized different vegetables into the categories roots, leaves, stems, seeds, and tubers. She also scribbled the notes, “1. Vitamins 2. Minerals 3. Roughage.” It’s amazing to see a student of a 1940s home economics course brought to life through her interactions with a textbook. | |||

<gallery mode="packed" perrow=5 heights=250px> | |||

: | File:IMG-0326.jpg|Peach Short Cake | ||

File:IMG-0329.jpg|Hamburg Stew | |||

File:IMG-0323.jpg|Vegetables | |||

File:IMG-0319.jpg|Front Inside Cover | |||

File:IMG-0322.jpg|Italian Spaghetti | |||

</gallery> | |||

=Significance= | |||

Overall, the Home Economics Textbook is a reflection on the past, on the role of young women and wives in the 1940s and the expectations placed upon them from a young age. Home economics raises a question that remains relevant to this day. What role should the government and public school systems play in teaching young children basic skills and “non-academic” lessons? If lessons such as these aren’t the governments responsibility, then where are children expected to learn it? Are we not placing yet another unfair advantage on students who don’t have stable homes or those whose parents don’t have the time to teach them skills such as cooking, cleaning, and changing a tire? In the feminist movements of the 1960s and 1970s, anti-Home Economics sentiment grew and in response to the backlash, Home economics courses are nearly completely extinct.<ref>Rowbotham, Sheila. The Past is before Us - Feminism in Action since the 1960s. Pandora, 1989.</ref> But is the abolishment of home economics really the answer? Or should public education be considering a reinstatement of “home economics” in a non-gendered format where all students are taught a form of both “home ec” and [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Industrial_arts “shop?”] | |||

''Home Economics Foods and Food Preparation'' gives us a look into the life of a young student and the expectations placed on girls in the 1940s to be caretakers and wives. It makes us think about the implications of mass produced documents and the reach they have. And it makes us contemplate our current education system and understand how it has changed throughout history. Finally, ''Home Economics Foods and Food Preparation'' reminds us that even in cheap, popular, mass produced documents, you can still find something special and marginalia often tells a completely new story than the one stamped into the pages. | |||

=References= | =References= | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

Latest revision as of 13:56, 3 May 2022

Home Economics Foods and Food Preparation is a series of cooking class leaflets created by the School District of Philadelphia. It is available at the Kislak Center for Special Collections at The University of Pennsylvania. The book was used in a Home Economics course in Philadelphia Public School and was published in 1942. It contains recipes and instructions for cleaning, caring, and cooking. While the textbook itself is generic and mass produced, this particular copy was owned by a female student, Edith Fineberg, and contains her unique notes, recipes, and doodles within the pages and on the covers. The book is full of her personality and becomes a beautiful view into the past. It shows how young girls were taught to be members of society and the expectations placed on them from a young age.

Background

Home Economics

Home Economics originated in the early 1900s as part of a movement aimed at preparing young women for professional jobs by equipping them with basic skills like cooking, cleaning, and home care. The course was created as a form of science.[1] Female students wore lab coats and were taught necessary skills that could help them procure a wide range of jobs for their future. It was created to help women gain independence as part of the liberal feminist movement of the early 1900s.[2] The Federal Bureau of Home Economics was erected around the same time. The government organization helped teach women during the first world war how to cook with the limited food supplies, had an advice radio show, published recipes, and taught lessons on food and nutrition.[3] There was a focus in American culture that the home could contribute to social change. Managing a properly fed and cared for nuclear family was a way in which young women could have a powerful impact on the future of the country.[4] But in the 1950s there was a major shift in the feminist movement that highlighted how the current structure was a conformist and repressive culture. The home economics field became a primary example for feminists in the 1960s of sexist, inhibitory culture. In response to the backlash the field is no longer studied or taught.

Chef Fritz Blank

The textbook was donated to the Penn Library in 2008 by Chef Fritz Blank, in the largest donation of cookbooks the library has received. Chef Fritz owned a famous restaurant in Philadelphia called Deux Cheminees, one of the first high-end restaurants in Philadelphia. It was opened in 1979 and it brought classic French style cooking to the growing Philadelphia restaurant scene.

The restaurant was located in two conjoined townhouses decorated to feel cozy and homey. The restaurant was full of bookcases of Chef Fritz's extensive cookbook collection. This particular cookbook stands out, as Chef Fritz was very interested in teaching children. He would go to Philadelphia schools and run cooking classes. Though the book appears to be very generic, as there are thousands of copies of this specific textbook. This one is special for its marginalia and the history behind it.

The Textbook

Structure

Home Economics Foods and Food Preparation was bound by W. Newkirk. Indented into the front cover is “BOUND BY W. NEWKIRK 186 W. NEDRO AVE. PHILA, PA." After extensive research, information on W. Newkirk was hard to come by. Though the address listed on the cover, 186 W. Nedro Ave, was home to the Newkirk family in the 1940s. Any more information on Newkirk is inconclusive. It's possible that he exclusively ran a book binding business, or maybe he bound books in addition to working other jobs. The book itself is bound for durability. There are three thick staples holding together the pages, almost like a pamphlet. The staples are holding just about the maximum amount of pages they can while maintaining the integrity of the book. The book is a series of leaflets. There is no pagination which could mean that the leaflets were printed separately and put together after printing.[5] The back cover is close to falling off while the front cover and each page is still fully in tact. The front and back cover are likely sturdy cardboard able to endure years of being shoved into book bags, held by children and worn down. These textbooks were designed for practical, functional use by a schoolchild, they were not designed for leisure reading. The books are not beautiful, and they are certainly not expensive. There is nothing elegant about the binding, it is simply functional. The textbooks were produced as cheaply as possible. Nothing could be more generic than these government issued textbooks.

Content

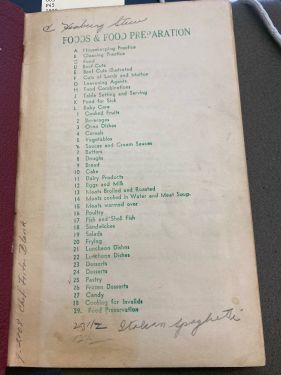

The book is broken up into 40 separate sections. The sections are laid out on the first page of the book in green-colored text—one of the only two pages with color in the book. There is no title page, just an index with each leaflet section title and number. The first eleven sections are labeled A-L while the subsequent 29 are labeled 1-29. Sections A-L include titles such as “Housekeeping Practice,” “Cleaning Practice,” and “Baby Care.” These sections are quite informative and give a clear set of rules for those to follow. For example, in “Food for the Sick,” there are lists of appropriate foods and their best preparations, a “rules for serving” section, and a seemingly never-ending list of cooking do’s and don’ts. The format is largely based on strict rules, instructions that are clear and easy to follow. The textbook is full of commands rather than recommendations. Textbook lines include: “Avoid discussing food in the presence of the patient and do not ask the patient what she wants.” This textbook approached Home Economics similar to how a mathematics textbook functions. The rules were definitive, leaving little room for creativity. This reflects a way in which the Philadelphia public school system was teaching all of their courses—focused heavily on yes or no answers and memorization rather than creativity. This home economics textbook is an example of the form of education being taught to students in the 1940s.

-

Index

-

"Food for the Sick"

The numbered sections are recipes. The organization of the recipes is a bit peculiar. It begins with basics, breads, and breakfasts but scatters other sections like “cereal” and “cake” in seemingly random sections of the book. The recipes are very simple and easy to follow. This textbook was probably made for middle school students considering the simplicity of the recipes.[6] It is a starting point for cooking and teaches many basics that one can carry with them.

Edith Fineberg

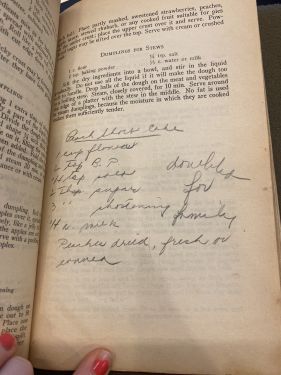

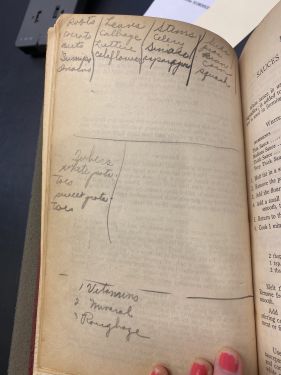

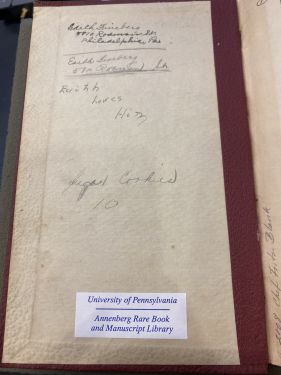

There are a number of scribbles and notes in the book. Most notably, the front inside cover has the name Edith Fineberg and her address 5810 Rodman St. Philadelphia, PA. The name and address is written twice. Underneath her name, Edith wrote “Edith loves him” and scribbled a little note to herself that section 10 has sugar cookies. Edith lived in West Philly in the 1940s, a predominantly Jewish neighborhood in Philadelphia at the time.[7] Other sparks of Edith’s personality shine through the book. She scribbled-in-pencil her own recipe in her own added-in chapter, number “29 ½”—for “Italian Spaghetti." There is another recipe for “Hamburg Stew” and one for “Peach Short Cake.” These recipes don’t appear elsewhere in the book. Maybe they were taught to her by her teacher or maybe she had assignments to bring in or create her own recipes. On the back of leaflet 5, Vegetables, you can see her notes from an activity in class or a homework assignment. Edith organized different vegetables into the categories roots, leaves, stems, seeds, and tubers. She also scribbled the notes, “1. Vitamins 2. Minerals 3. Roughage.” It’s amazing to see a student of a 1940s home economics course brought to life through her interactions with a textbook.

-

Peach Short Cake

-

Hamburg Stew

-

Vegetables

-

Front Inside Cover

-

Italian Spaghetti

Significance

Overall, the Home Economics Textbook is a reflection on the past, on the role of young women and wives in the 1940s and the expectations placed upon them from a young age. Home economics raises a question that remains relevant to this day. What role should the government and public school systems play in teaching young children basic skills and “non-academic” lessons? If lessons such as these aren’t the governments responsibility, then where are children expected to learn it? Are we not placing yet another unfair advantage on students who don’t have stable homes or those whose parents don’t have the time to teach them skills such as cooking, cleaning, and changing a tire? In the feminist movements of the 1960s and 1970s, anti-Home Economics sentiment grew and in response to the backlash, Home economics courses are nearly completely extinct.[8] But is the abolishment of home economics really the answer? Or should public education be considering a reinstatement of “home economics” in a non-gendered format where all students are taught a form of both “home ec” and “shop?”

Home Economics Foods and Food Preparation gives us a look into the life of a young student and the expectations placed on girls in the 1940s to be caretakers and wives. It makes us think about the implications of mass produced documents and the reach they have. And it makes us contemplate our current education system and understand how it has changed throughout history. Finally, Home Economics Foods and Food Preparation reminds us that even in cheap, popular, mass produced documents, you can still find something special and marginalia often tells a completely new story than the one stamped into the pages.

References

- ↑ Elias, Megan J. Stir It Up: Home Economics in American Culture. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.

- ↑ Elias, Megan J. Stir It Up: Home Economics in American Culture. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.

- ↑ Parkin, Katherine J. Food Is Love: Advertising and Gender Roles in Modern America. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

- ↑ Parkin, Katherine J. Food Is Love: Advertising and Gender Roles in Modern America. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

- ↑ Stewart, A. A. The Printer's Dictionary of Technical Terms: a Handbook of Definitions and Information About Processes of Printing; with a Brief Glossary of Terms Used In Book Binding. Boston, Mass.: School of Printing, North End Union, 1912.

- ↑ Perkins, Wilma Lord. The Fannie Farmer junior cook book. Boston, USA. Little, Brown and Company. 1942.

- ↑ Joselit, Jenna Weissman, and Murray Friedman. “Jewish Life in Philadelphia, 1830-1940.” The Journal of American History., vol. 72, no. 3, Associated Publishers of American Records, 1985.

- ↑ Rowbotham, Sheila. The Past is before Us - Feminism in Action since the 1960s. Pandora, 1989.