Page Numbers

Page numbering is a feature that seems ubiquitous among modern books, but it is something modern readers take for granted. Though it seems like a simple device, it truly is an apparatus that had to be invented and developed. We should take a moment to appreciate pagination, as current reading technologies may soon render it obsolete.

Pagination is the consecutive numbering of book’s pages on both the recto and verso—front and back—sides. [1] Pagination supplanted foliation, another type of sequential numbering; foliation denotes leaves on its recto side.

History

Most books before the 1500s lacked page numbers. Around 1450, less than an estimated ten percent of manuscript books contained pagination, but by the early 16th century, readers were relying on them to find their way through texts. (Baron 33) [2] As a modern reader, it is hard to imagine navigating a book without pagination, yet somehow people did for many centuries.

Scrolls

Scroll culture lacked pagination because a scroll’s “text was continuous and lacked page breaks” (Lyons 35). [3] Though Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans of antiquity divided scrolls’ text and images into columns called paginae, the emergence of the codex—a collection of leaves bound on one side—after the first century AD introduced a new organizational mode through pages. [1]

Codex

Although the materiality of pages in a codex changed how readers approach a text, it still took a long time to shift reading culture and necessitate the use of pagination.

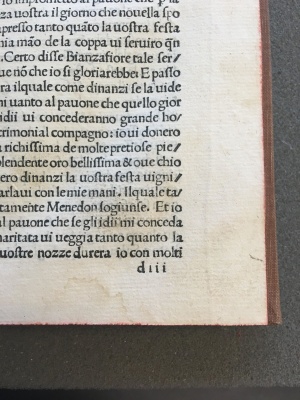

This is partly because page numbering was not necessary to produce a codex. Bookbinders did not assemble books by each page but instead dealt with groups of several leaves at once. To arrange these sections in the right order, binders marked each section with a letter of the alphabet, usually in the bottom right corner of the recto sheet. Numbers followed the letters to indicate the sequence of the leaves. Considering that this mark, called a “signature,” contained a combination of letters and numbers, and also considering that sections might have had an unequal number of leaves, these signatures were primarily for the artisans’ reference and not for the convenience of readers (Febvre 88). [4]. However, the custom of signature marks may have been a predecessor to pagination, as the earliest examples of pagination have no signatures, and vice versa [4]. Such an example is the book pictured in Figure 1 published in 1488; while there are signature marks throughout the pages, a book owner added his own page numbers in the top margins.

Reading culture

However, the habits of readers during early book history also made page numbers not necessary, at first. While today most of the literate population read “extensively” by reading a large number of texts (often only once), readers of antiquity read “intensively,” returning to only a few books repeatedly. [5] The manuscript production process influences the volume of books people read. Books were difficult to come by because of expensive parchment, but also because of the laborious process of copying and illuminating a hand-written manuscript. The painstaking nature of the process is clear by the length of time required to faithfully reproduce a manuscript: scribes usually copied three to four pages per day. [3] The scarcity of books results in early readers knowing their texts well, sometimes studying them to the point of memorization. Therefore, page numbers are less necessary to an intensive reader who knows the text by heart compared to an extensive reader who may be glancing over a text once for reference. An example of intensive reading is lectio reading, the predominant model for reading in the early Middle Ages. [1] Back then, “reading, understood as a spiritual exercise, emphasized the slow and steady contemplation of a single text”—that text being the Bible. [1] Knowing their text so well, page numbers as reminders of location were less necessary for a medieval reader. It is easier to understand, then, how monks were able to refer to specific verses by just quoting its first few words.

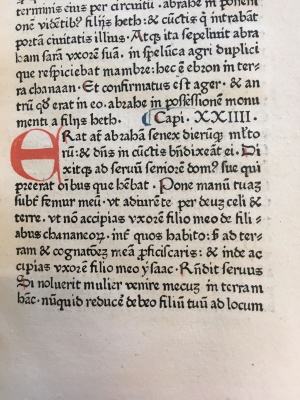

Still, artisans and readers developed devices to help navigate numberless texts. Their repertoire of markings, called paratexts, mostly involved decorative elements to help divide the text into subgroups and draw attention to some. For example, scribes could alter script style to highlight a prestigious passage, Latin words, names, or quotations. [6] “Capitulo,” or chapters, could split up the text into digestible sections. Running headers at the top of pages would indicate which section the reader was in. Illuminators could also paint enlarged or colored letters for titles and subtitles of new sections. In Figure 2, the Bible pictured was published by Anton Koberger in 1475, and ornamental letters indicate the beginning of capitulos. However, it is clear that these letters are essential for reference and not just decoration when looking at the same Bible’s Psalms, a commonly-read book of the Bible. Here, the colored letters are much more frequent to facilitate a reader’s eye to a specific verse.

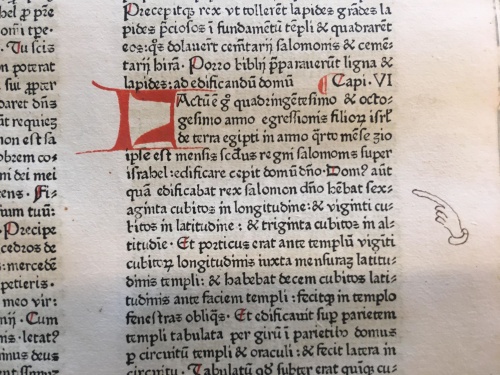

Readers developed their own paratexts, as well. Not only were book owners expected to write in their own page numbers, but they also drew their own markers in page margins. Commonly, readers drew a hand called a manicule to literally point out a passage of interest to help find it later.

By the twelfth century, reading culture began to shift. “The development of universities fostered analytical modes of engagement with text, especially in the urban, scholarly communities. Texts were once again being consulted for reference purposes.” [1] Such social factors that brought attention to secular matters, along with the invention of the printing press in the mid-fifteenth century that accelerated book production to a mass-scale, ushered in new reading customs. Therefore, readers needed new paratextual features such as indices—and page numbers—for their analytical purposes.

Perhaps the earliest extant example of pagination is Aldus Manutius’s edition of Niccolo Perotti’s Cornucopiae, published in 1499. [7] As a 700-page encyclopedia of the Latin language, it makes sense that the innovative Italian printer deemed the addition of “arithmeticis numeris” on each page necessary. [7] Manutius gave the pagination instructions, usually given to the reader through his prefaces, to the printer instead. But this publication was “distinctly out of place in his repertoire till then” and marked “a change in the editorial direction of the Aldine press.” [7] This is because the original Greek texts that Manutius originally printed were intellectually inaccessible to the majority of Italians. Therefore this first example of pagination also marks a new attentiveness to the convenience of readers with modernized interests.

We are now experiencing an interesting era of technology in which the digital format of electronic publications recalls the continuous text of ancient scrolls. “The boundaries of the digital page, like those of the paginae in the papyrus roll, need not be coextensive with the boundaries of the material platform.” [1] However, we are also reading alongside newly-developed computerized devices, like the FIND function that can identify the location of words in a digital document. Such tools may have made referencing documents through page numbers outdated. With such technologies aiding digital reading, the culture of reading itself may be shifting from a continuous activity to a “random-access” process that is more like “reading on the prowl.” [2] We are on the cusp of rapidly-transforming book culture, in which both bibliographic and reading conventions are in flux.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Mak, Bonnie. How the Page Matters. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Baron, Naomi. Words Onscreen. New York, New York: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Lyons, Martyn. Books: A Living History. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2011.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Febvre, Lucien. Coming of the Book London: Editions Albin Michel, 1958.

- ↑ Levy, Michelle and Mole, Tom. The Broadview Introduction to Book History. Ontario: Broadview Press, 2017

- ↑ Wakelin, Daniel. Designing English. Oxford: Bodleian Library, 2018

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Davies, Martin. Aldus Manutius: Printer and Publisher of Renaissance Venice. London: The British Library, 1995.