Early Duplicators

-

This machines was used by the Belgian resistance for producing underground newspapers and pamphlets.

-

The National Cultural History Museum in Boom Street, Pretoria.

-

Jackson & O'Sullivan "The NATIONAL" Duplicator. Made in Brisbane, Queensland during World War II.

Introduction

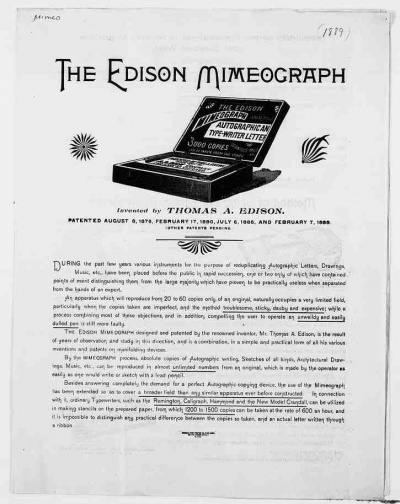

In November 1968, Changing Times identified nine principal alternatives to “real printing”.[2] Including a table of common uses and suitable quantity ranges, the article targets less affluent individuals looking to save by means of the “highly competitive trade” of printing. This article is among many indicators of a pivotal moment of transition in the history of printing in the United States. From Eugenio de Zuccato’s Papyrograph and Typograph to Thomas Edison’s Electric Pen and Mimeograph, the sudden invention of countless copying machines revolutionized the printing industry. Though the practical history of early duplicators is often characterized by ambiguity and imprecision, the cultural history of copying is rich with insight on social movements catalyzed by minorities. These social movements were made possible by a new potential for disseminating information that early copiers afforded under-represented groups. Despite the plethora of duplicating technologies, this paper will focus on the mimeograph as the face of their social ramifications. According to an article in Office Systems, a popular magazine in the late 1900s, the “most popular and cost effective technologies for producing multiple copies were mimeograph machines and spirit or stencil duplicators”.[3] Patented as number 180,857 on August 8, 1876, the "Improvement in Autographic Printing” invented by Thomas Edison would later become known as the mimeograph.[4] After AB Dick Company licensed the technology from Edison, mimeographs came into everyday use in the 1900s.[1] The machines, which utilized the drum of a rotary machine to force ink through the holes of a stencil, were marketed as “The Edison Mimeograph”.[5] In the span of only several decades, any and all individuals had access to what only an elite bracket of society once did: printing.

Ramifications of the Technology

The use of these technologies became progressively more widespread. Remnants of one such duplicator, stored in the University of Pennsylvania’s rare collections is kept in its original box which advertises the copier as “…a tremendous aid to businessmen, salesmen, schoolteachers, clubs, churches, and fraternal organizations”.[6] Early copiers became a central tool in education, often used to copy assignments and handouts; knowing how to operate a copier became a necessary prerequisite to entering the education industry.[7] They also decreased barriers to entry in various professional fields, proliferating the economy in ways similar to that of inventing the moveable type. Among the countless social impacts the invention of copiers resulted in, the use of mimeographs for low-budget publishing was one that created new waves of art and free expression. Examining case studies of those involved in underground printing during the 1960s shows more closely how these waves ultimately created a cultural revolution.

Based on a 1998 exhibition at The New York Public library, Steven Clay and Rodney Phillips’s, A Secret Location on the Lower East Side: Adventures in Writing:1960-1980, functions as a sourcebook of information on the Mimeo Revolution. It clarifies that the term is “a misnomer in the sense that well over half the materials produced under its banner were not strictly produced on the mimeograph machine”.[8] In actuality, the Mimeograph Revolution was a period defined by small scale publishing facilitated by the access to cheap, and often non-commercial printing. Two specific texts, a counterculture poem and a personal diary, elucidate the role of early duplicators in the emergence of this movement.

- Hekto-Printer gelatin transfer duplicator, by Heyer, Inc.

-

Remnants of an image of nature on a duplicating sheet.

-

Inverted image of remnants of duplicating sheet, text titled "Come and See".

-

Remnants of both written and typed text on duplicating sheet.

A Counterculture Poem

Published in 1960, Donald M. Allen's poetry anthology, The New American Poetry: 1945-1960, presented an ensemble of writing central to the start of the movement, all of which share a “total rejection of all those qualities typical of academic verse”.[9] Allen goes on to claim that these poets, who “created their own tradition, their own press, and their public”, are the “avant-garde, the true continuers of the modern movement in American poetry”. As many artists participating in the mimeo revolution existed outside mainstream publication and distribution channels, “underground” magazines and presses evolved throughout the 1960s and 70s.

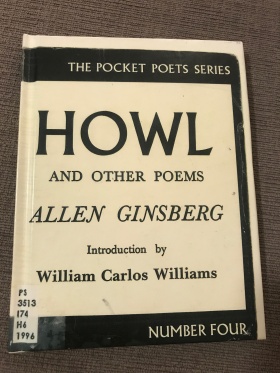

The first case study is often considered a critical piece of counterculture literary work that contributed to the Mimeo Movement but also acted as one of the founders of the Beat Generation, celebrating non-conformity and creativity. Howl, by Allen Ginsberg, is famously known for having gone to trial in 1957 on grounds of obscenity. The poem, which seems chaotic at first, is broken into three sections that comment on the state of the American middle class in ways considered radical at the time.[11] In the first section, Ginsberg calls a variety of underrepresented groups the “best minds” of his generation, going into their experiences in graphic detail; the second section goes into detail on the state of industrial civilization, criticizing capitalism and mainstream culture; and the third section explores the concept of solidarity within restrictive institutional structures. Published officially after the initial releasing of several mimeographed copies, the radical content of the book further contributes to its essence as a key composition of the Mimeo Revolution.

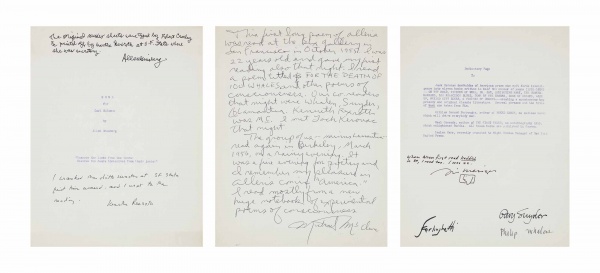

Ginsberg’s mimeographed copies of Howl sell today at auctions for thousands of dollars.[12] According to one online book firm, only twenty-five copies were made on rectos in purple ink, typed “by the poet Robert Creeley and printed by Marthe Rexroth at S.F State, where she was a secretary".[13] The mimeograph prints were made to be disseminated at the Six Gallery reading, which took place at 3110 Fillmore Street in San Francisco on October 7, 1955; today, the event is considered “the first important public poetry exhibition heralding the West Coast literary revolution of the Beat Generation.” The history accompanying the poem’s debut confirms that Howl was originally created for an underground audience. However, the mimeograph method used to produce these first copies is not only a testament to the context in which the text was written. Rather, the genre itself is modeled in its technology, which emanates a sense of rebelliousness consistent with the Six Gallery reading event. Ginsberg’s use of an early duplicating technology for printing positioned Howl outside the mainstream from the moment the poem came into the public.

Today, Ginsberg’s mimeographed copies of Howl possess value beyond their material worth. The mimeograph prints are no longer cheaper, earlier drafts of Howl, but instead hosts to deep cultural significance. The prints have immense historical importance, as they attracted the attention of poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti of City Lights Books, who later went on to publish Howl and launch Ginsberg’s career. City Lights Books itself was the “very image of the counterculture,” initially only selling paperbacks and magazines.[8] When paperback copies of Howl were released in the United States, Ferlinghetti and his partner, Shigeyosi Murao, were arrested by San Francisco police on obscenity charges. The court case was widely publicized, and Ferlinghetti’s acquittal was celebrated as a victory on the part of the literary movement to which Ginsberg belonged--the trials brought the Beat Movement and Ginsberg’s Howl to public attention. The text that had started off in the form of mimeograph pamphlets at a discreet event was catapulted into the national spotlight. Ironically, the very copies that once rejected elitism in favor of free expression and accessibility now circulate within upper class art markets.

In many ways the twenty five mimeograph prints of Howl fill a cultural gap, memorializing the underground origins of Ginsberg’s art despite the text eventually becoming standardized and disseminated as part of the mainstream. In this way, Ginsberg’s Howl is a classic example of how early duplicating machines led to a revolution of groundbreaking literature and art. The existence of such copying technologies often gave writers like Ginsberg the leverage to gain endorsement and recognition. Regardless of whether or not Ginsberg himself desired the fame he acquired, the mimeograph became the avenue through which underground texts like Howl came to the forefront of American literary media.

A Mimeograph Biography

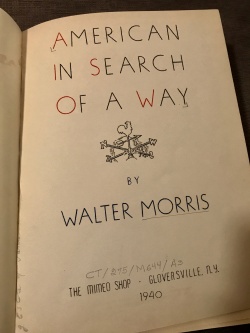

The second case study is that of an underground publisher. Written in first person, American In Search of a Way is an autobiographical "notebook" of Walter Ripton Morris, a mimeograph shop owner based in Gloversville, NY. After getting his A.B. at the University of Michigan in 1932, Morris completed two years of graduate level work, worked in Detroit for a year, and then returned to Gloversville, New York, to run the mimeograph shop where he would eventually print his own work. The mimeograph copy of Morris’ work, published in 1940, is done in a clean two column layout, with running headers and an introduction. Even while Morris calls his work a “diary”, the stylistic appearance of the book is highly polished. There is a tension between the archetypically handwritten, unedited, and personal genre and the sophistication in Morris’ work. On first glance, Morris’ use of the mimeograph seemingly gives him access to a level of professionalism that justifies his act of publishing.

However, Morris already had access to dominant structures of printing and publishing, indicating that his use of the mimeograph is much more nuanced. Though Morris did self-produce copies of his book, he also received two Hopwood Contest awards for segments of his journal in 1933 and 1934 and published officially through Macmillan Company in 1934 before ever owning his own mimeograph shop. The Michigan alumni newsletter calls his work the “first non-fiction prose manuscript in the major contest to be published in book form”. Id. Morris’ mode of publishing defies expectations by challenging the principal that mimeographs are used by those that need to. Instead, American In Search of a Way uses the mimeograph technology in a way that rubs against the gain, by harnessing it’s symbolic value to further create meaning.

Upon opening the mimeo shop at the very end of the 1930s, Morris found a platform on which to fuse the roles of writer and publisher. Morris even addresses issues of mainstream printing presses in the book itself, claiming that “political pressures on a novelist, the demands of practical struggle, is likely to force his work into melodrama” (Morris, 32). Unlike literature confined by limitations determined by publishers, Morris’s autobiography covers a wide breadth of topics aside from his personal life from 1934 to 1940, including religion, politics, and philosophy. Morris’ mimeo shop provides him the platform on which to avoid these issues and instead create a one-man production. In collapsing “the relations between writer, editor, reader, and publisher”, Morris and other progressive publishers become the backbone of what would become the Mimeograph Revolution.[14] Despite evidence that Morris’ could have gone to a major publisher as he had done initially, his use of the mimeograph demonstrates that the physical appearance of the book is highly performative.

The entirety of the book performs the spirit of an independent publisher. For example, in his introduction, Morris writes “this mimeographed edition is a selection from the original notebooks” (Morris, i.). In this line, the book accomplishes what authors tied to more traditional modes of printing could not; the materiality of the book is addressed in the content itself, proof that the author, and in this case the narrator, has agency over the entirety of the work. This quality of Morris’ book sets his work apart from other uses of early duplicators. Like Howl, America In Search of a Way possesses a materiality that models its content. Just as both Ginsberg and Morris support the middle class and fringe movements, the mimeographed copies of their books are hand done and not mass produced. However, Morris’ use of the mimeograph is stylistically intentional, and it creates the effect of signaling through form in addition to content. The book capitalizes on the semantics and affordances of the mimeograph technology, stretching the limits of early duplicator uses.

Conclusion

Overall, the unprecedented outpouring of poetry books and magazines published in non-traditional ways brought alternative cultures to light. Mimeo publishing “offered a ‘third way’ toward seizing the means of textual production, bypassing establishment periodicals”.[14] In this way, cheaper printing technologies created avenues for subversive literature to take center stage. Ginsberg’s Howl, which began as twenty five mimeographed copies, is a classic example of the way early duplicators facilitated the Mimeograph Revolution. If moveable type sanctioned the democratization of scholarly learning by enabling the mass production of print, the creation of early copying machines democratized distribution access by enabling large-scale duplication of originals. Moreover, this phenomenon gave the mimeograph and other duplicators cultural significance; the technologies themselves took on identities associated with the avant-garde. Morris substantiates these associations by using them semantically to match form with content in his autobiography, American in Search of a Way. Morris’ text shows that mimeographs not only enabled, but also advanced the Mimeograph Revolution.

By the 2000s, early copiers such as the spirit duplicator had become technologies of the past—for example, in the letters segment of Harper’s Magazine’s October 1999 issue, one contributor reminisces about the messy process of “ditto machines”. However, the legacy that early duplicating machines left on the world lives on in the seams of print history and in various narratives of free expression.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Dick (A.B.) Co to Thomas A. Edison, 10 March 1887, Thomas A. Edison Papers Digital Edition LB024149 (1 Dec. 2018) http://edison.rutgers.edu/NamesSearch/SingleDoc.php?DocId=LB024149.

- ↑ "Cheap Ways to Get Things "Printed"." Changing Times (pre-1986) 22.11 (1968): 35. ProQuest. 1 Oct. 2018. https://proxy.library.upenn.edu:2072/docview/199147770/fulltextPDF/45D02535E801424DPQ/1?accountid=14707

- ↑ Regan, Kerry. "The Copier." Office Systems 16.12 (1999): 29-31. ProQuest. Web. 12 Dec. 2018. https://proxy.library.upenn.edu:2072/docview/216426989/fulltextPDF/34E8C7CD06E84E3EPQ/1?accountid=14707

- ↑ Jefferson, Thomas. Google Patents Database. US 180,857A, United States Patent and Trademark Office, 8 August 1876. https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/d9/32/da/0f54852396c215/US180857.pdf

- ↑ Dick (A.B.) Co, 1889, Thomas A. Edison Papers Digital Edition CA035A (1 Dec. 2018) http://edison.rutgers.edu/NamesSearch/SingleDoc.php?DocId=CA035A

- ↑ [hekto-printer Gelatin Transfer Duplicator, by Heyer, Inc.]. https://franklin.library.upenn.edu/catalog/FRANKLIN_9977255992003681

- ↑ Mueller, Dennis Raymond. "Identification and Classification of Teacher Tasks Appropriate to Pre-Student Teaching, Field-Based, Industrial Arts Teacher Education." Order No. 8001788 The Ohio State University, 1979. pg. 118. Ann Arbor: ProQuest. Web. 12 Dec. 2018. https://proxy.library.upenn.edu:2072/docview/302959734/previewPDF/26EAB942B34D4242PQ/1?accountid=14707

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Clay, Stephen, and Rodney Phillips. A Secret Location On the Lower East Side : Adventures In Writing, 1960-1980 : a Sourcebook of Information. New York: New York Public Library and Granary Books, 1998.

- ↑ Allen, Donald M. The New American Poetry, 1945-1960 /. New York :: Grove Press, pg.xi, 1960. Print.

- ↑ Howl, for Carl Solomon. Christie's. Photo by Unknown.

- ↑ Ginsberg, Allen. Howl and Other Poems. San Francisco: City Lights Books, 2003.

- ↑ Howl, for Carl Solomon. Mimeographed for the Six Gallery Reading. Raptis Rare Books, 2016, www.raptisrarebooks.com/product/howl-allen-ginsberg-six-gallery-beat-generation/.

- ↑ Howl, for Carl Solomon. Mimeographed for the Six Gallery Reading. Raptis Rare Books, 2016, www.raptisrarebooks.com/product/howl-allen-ginsberg-six-gallery-beat-generation/.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Lawrence, N. R. “Mimeo Fever: Sixties Small Press within a Global Context.” 49th parallel : an interdisciplinary journal of North American studies. 19 (2006).

Further Resources

- Museum of Printing in Haverhill, Massachusetts: https://www.museumofprinting.org/about-mop/

- The Office Museum, Copying Machines: https://www.officemuseum.com/copy_machines.htm

- “Join Me in the 1900s”, blog by Webmaster, Pat Gryer: https://www.1900s.org.uk/banda.htm#pagetop

- Supply Source, Tenafly NJ. President: Fred Keen. https://www.manta.com/c/mx2r8rk/supply-source-llc-repeatotype

License

The content on this page of the is licensed Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International. To understand your rights as a user of this website, please see this page: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/