Early Duplicators

Introduction

In November 1968, Changing Times identified nine principal alternatives to “real printing”.[2] Including a table of common uses and suitable quantity ranges, the article targets less affluent individuals looking to save by means of the “highly competitive trade” of printing. This article is among many indicators of a pivotal moment of transition in the history of printing in the United States. From Eugenio de Zuccato’s Papyrograph and Typograph to Thomas Edison’s Electric Pen and Mimeograph, the sudden invention of countless copying machines revolutionized the printing industry. Though the practical history of early duplicators is often characterized by ambiguity and imprecision, the cultural history of copying is rich with insight on social movements catalyzed by minorities. These social movements were made possible by a new potential for disseminating information that early copiers afforded under-represented groups.

Despite the plethora of duplicating technologies, this paper will focus on the mimeograph as the face of their social ramifications. According to an article in Office Systems, a popular magazine in the late 1900s, the “most popular and cost effective technologies for producing multiple copies were mimeograph machines and spirit or stencil duplicators”. Patented as number 180,857 on August 8, 1876, the "Improvement in Autographic Printing” invented by Thomas Edison would later become known as the mimeograph. After AB Dick Company licensed the technology from Edison, mimeographs came into everyday use in the 1900s. The machines, which utilized the drum of a rotary machine to force ink through the holes of a stencil, were marketed as “The Edison Mimeograph”. In the span of only several decades, any and all individuals had access to what only an elite bracket of society once did: printing.

Ramifications of the Technology

- Hekto-Printer gelatin transfer duplicator, by Heyer, Inc.

-

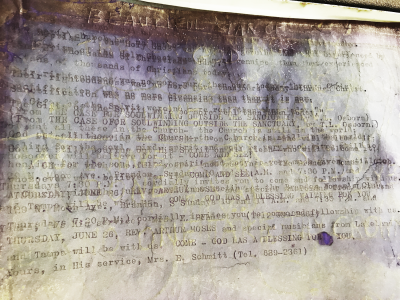

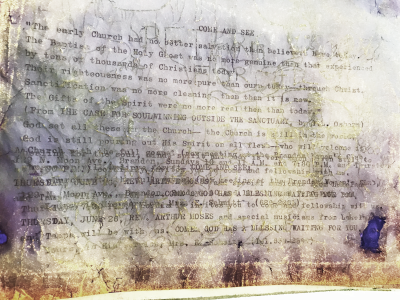

Remnants of an image on a sheet with. The

-

caption.

-

caption.

The use of these technologies became progressively more widespread. Remnants of one such duplicator, stored in the University of Pennsylvania’s rare collections is kept in its original box which advertises the copier as “…a tremendous aid to businessmen, salesmen, schoolteachers, clubs, churches, and fraternal organizations”. Early copiers became a central tool in education, often used to copy assignments and handouts; knowing how to operate a copier became a necessary prerequisite to entering the education industry (Mueller, 118). They also decreased barriers to entry in various professional fields, proliferating the economy in ways similar to that of inventing the moveable type. Among the countless social impacts the invention of copiers resulted in, the use of mimeographs for low-budget publishing was one that created new waves of art and free expression. Examining case studies of those involved in underground printing during the 1960s shows more closely how these waves ultimately created a cultural revolution.

Preview: two works from..represent this. Based on a 1998 exhibition at The New York Public library, Steven Clay and Rodney Phillips’s, A Secret Location on the Lower East Side: Adventures in Writing:1960-1980, functions as a sourcebook of information on the Mimeo Revolution. It clarifies that the term is “a misnomer in the sense that well over half the materials produced under its banner were not strictly produced on the mimeograph machine” (Clay, 14). In actuality, The Mimeograph Revolution was a period defined by small scale publishing facilitated by the access to cheap, and often non-commercial printing.

A Counterculture Poem

A Mimeograph Biography

Notes

License

The content on this page of the is licensed Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International. To understand your rights as a user of this website, please see this page: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/