Early Duplicators: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

[[File:Hekto-Printer gelatin transfer duplicator 5.png|thumb|caption]] | [[File:Hekto-Printer gelatin transfer duplicator 5.png|thumb|caption]] | ||

<gallery mode="slideshow" gallery widths=300px heights=300px caption="Click For Slideshow"> | |||

File:Hekto-Printer_gelatin_transfer_duplicator_1.jpeg|200BLAHCAPTOON | |||

File:Hekto-Printer_gelatin_transfer_duplicator_2.jpeg|200px | |||

File:Hekto-Printer_gelatin_transfer_duplicator_3.jpeg|300px|caption. | |||

File:Hekto-Printer_gelatin_transfer_duplicator_4.png|300px|caption. | |||

File:Hekto-Printer_gelatin_transfer_duplicator_5.png|300px|caption. | |||

</gallery> | |||

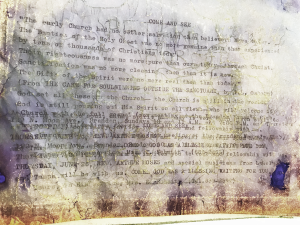

[[File:Phil's illustrations for mimeographed poems about daily life.jpg|thumb|Phil Venditti, “1958 or 1959--Phil's illustrations for mimeographed poems about daily life--Adams Elementary School--Wichita, Kansas”, from Flickr, Creative Commons. Photo by Unknown, taken 11/9/2018.]] | [[File:Phil's illustrations for mimeographed poems about daily life.jpg|thumb|Phil Venditti, “1958 or 1959--Phil's illustrations for mimeographed poems about daily life--Adams Elementary School--Wichita, Kansas”, from Flickr, Creative Commons. Photo by Unknown, taken 11/9/2018.]] | ||

Revision as of 19:51, 10 December 2018

Though the practical history of early duplicators is often characterized by ambiguity and imprecision, the cultural history of copying is rich with insight on social movements catalyzed by minorities. Blah. [1]

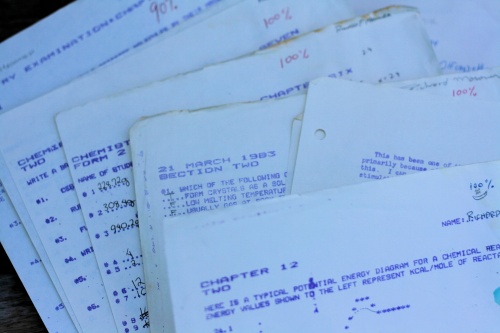

In November 1968, Changing Times identified nine principal alternatives to “real printing”. Including a table of common uses and suitable quantity ranges, the article targets less affluent individuals looking to save by means of the “highly competitive trade” of printing. This article is among many indicators of a pivotal moment of transition in the history of printing in the United States. From Eugenio de Zuccato’s Papyrograph and Typograph to Thomas Edison’s Electric Pen and Mimeograph, the sudden invention of countless copying machines revolutionized the printing industry. Though the practical history of early duplicators is often characterized by ambiguity and imprecision, the cultural history of copying is rich with insight on social movements catalyzed by minorities. These social movements were made possible by a new potential for disseminating information that early copiers afforded under-represented groups. According to an article in Office Systems, a popular magazine in the late 1900s, the “most popular and cost effective technologies for producing multiple copies were mimeograph machines and spirit or stencil duplicators”. Mimeographs came into use in the 1900s. The machines utilized the drum of a rotary machine to force ink through the holes of a stencil. The Spirit Duplicator, invented in the 1920s, was also called the Ditto in North America. It used a similar technique to the mimeograph, requiring a master sheet to hand-transfer pressure onto a second sheet coated with colored wax, producing a mirror image. In the span of only several decades, any and all individuals had access to what only an elite bracket of society once did: printing. The use of these technologies became progressively more widespread. Remnants of one such duplicator, stored in the University of Pennsylvania’s rare collections is kept in its original box which advertises the copier as “…a tremendous aid to businessmen, salesmen, schoolteachers, clubs, churches, and fraternal organizations” (Heyer, Inc.). Early copiers became a central tool in education, often used to copy assignments and handouts; knowing how to operate a copier became a necessary prerequisite to entering the education industry (Mueller, 118). They also decreased barriers to entry in various professional fields, proliferating the economy in ways similar to that of inventing the moveable type. Among the countless social impacts the invention of copiers resulted in, the use of mimeographs for low-budget publishing was one that created new waves of art and free expression. Examining case studies of those involved in underground printing during the 1960s shows more closely how the these waves ultimately created a cultural revolution. Preview: two works from..represent this. Based on a 1998 exhibition at The New York Public library, Steven Clay and Rodney Phillips’s, A Secret Location on the Lower East Side: Adventures in Writing:1960-1980, functions as a sourcebook of information on the Mimeo Revolution. It clarifies that the term is “a misnomer in the sense that well over half the materials produced under its banner were not strictly produced on the mimeograph machine” (Clay, 14). In actuality, The Mimeograph Revolution was a period defined by small scale publishing facilitated by the accessibility to cheap, and often non-commercial printing.

A Counterculture Poem

Published in 1960, Donald M. Allen's poetry anthology, The New American Poetry: 1945-1960, presented an ensemble of writing central to the start of the movement, all of which share a “total rejection of all those qualities typical of academic verse” (Allen, xi.). Allen goes on to claim that these poets, who “created their own tradition, their own press, and their public”, are the “avant-garde, the true continuers of the modern movement in American poetry”. Id. As many artists participating in the mimeo revolution existed outside mainstream publication and distribution channels, “underground” magazines and presses evolved throughout the 1960s and 70s. The first case study is often considered a critical piece of counterculture literary work that contributed to the Mimeo Movement but also acted as one of the founders of the Beat Generation, celebrating non-conformity and creativity. Howl, by Allen Ginsberg, is famously known for having gone to trial in 1957 on the ground of obscenity. The poem, which seems chaotic at first, is broken into three sections that comment on the state of the American middle class in ways considered radical at the time. In the first section, Ginsberg calls a variety of underrepresented groups the “best minds” of his generation, going into their experiences in graphic detail; the second section goes into detail on the state of industrial civilization, criticizing capitalism and mainstream culture; and the third section explores the concept of solidarity within restrictive institutional structures. Published by poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti of City Lights Books, the radical content of the book further contributes to its essence as a key composition of the Mimeo Revolution. The court case was widely publicized, and Ferlinghetti’s acquittal was largely seen as a victory on the part of the literary movement to which Ginsberg belonged. Ginsberg had mimeographed copies of Howl, which sell today at auctions for thousands of dollars. According to —-, Ginsberg only produced twenty-five copies Moreover, City Lights Books itself is the “very image of the counterculture”, initially only selling paperbacks and magazines (Clay, 45).

A Mimeograph Biography

The first case study is that of an underground publisher. Written in first person, American In Search of a Way is an autobiographical "notebook" of Walter Ripton Morris, a mimeograph shop owner based in Gloversville, NY. After getting his A.B. at the University of Michigan in 1932, Morris completed two years of graduate level work, worked in Detroit for a year, and then returned to Gloversville, New York, to run the mimeograph shop where he would eventually print his own work. The entirety of the book embodies the spirit of an independent publisher. For example, in his introduction, Morris writes “this mimeographed edition is a selection from the original notebooks” (Morris, i.). In this line, the book accomplishes what authors tied to more traditional modes of printing could not; the materiality of the book is addressed in the content itself, proof that the author, and in this case the narrator, has agency over the entirety of the work. connection to freedom of expression, focus on one edition vs. mass production Though Morris self-produced copies of his book, he also received two Hopwood Contest awards for segments of his journal in 1933 and 1934 and previously published officially through Macmillan Company in 1934. The Michigan alumni newsletter calls his work the “first non-fiction prose manuscript in the major contest to be published in book form”. Id. The mimeograph copy of Morris’ work is done in a clean two column layout, with running headers and a an introduction. Even while Morris calls his work “——” , the stylistic appearance of the book is highly polished; there is a tension between the archetypically handwritten, unedited, and personal genre and the professionalism in Morris’ work. On first glance, Morris’ use of the mimeograph seems similar to Gai credibility.

he calls it a notebook he starts out by saying what it is…diary, journal, notebook? super clean, typed it out, with running headers tension, manuscript handwritten style genre but producing them in a clean book, he has control over appearance. what is the mimeo to him? Signaling it as a mimeo, my diary? is he an exception? what it seems like it did: gives him more credibility, gives him access to a level of professionalism that he otherwise wouln’t have been able to afford, freedom to make his decision — personal diary to book, BUT didn’t. symbolic. one snse, it was a way to publish for expel who didn’t have any emans, but in this case…

Upon opening the mimeo shop at the very end of the 1930s, Morris finds a platform on which to fuse the roles of writer and publisher. Morris even addressed issues of mainstream printing presses, claiming that “political pressures on a novelist, the demands of practical struggle, is likely to force his work into melodrama” (Morris, 32). Unlike literature confined by limitations determined by publishers, Morris’s autobiography covers a wide breadth of topics aside from his personal life from 1934 to 1940, including religion, politics, and philosophy. Morris’ mimeo shop provides him the platform on which to avoid these issues and instead create a one-man production. In collapsing “the relations between writer, editor, reader, and publisher”, Morris and other progressive publishers become the backbone of what would become the Mimeograph Revolution (Lawrence). Morris’ America In Search of a Way functions new form of art,

Notes

- ↑ Author, Book, pg. #.