EPub: Difference between revisions

(→What is ePub?: moving the timeline) |

|||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

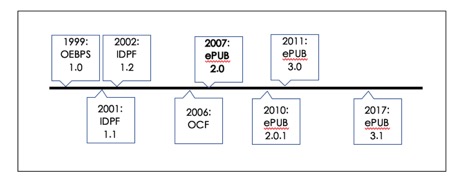

Electronic publishing came into the public view in 1999, through a format called the “Open eBook Publication Structure,” or OEBPS. <ref name= "Bit of History" >“A Bit of History.” EDRL Lab, accessed September 28, 2018. https://www.edrlab.org/epub/a-bit-of-history/ </ref> This format serves as a set of specifications for the “content, structure, and presentation of electronic books.” <ref name= "OEBPS"> “OEBPS (Open Ebook Forum Publication Structure) 1.2.” Library of Congress (2012). Last modified February 2012. </ref> Essentially, it is the set of standards required for electronic publishing. The body that selected the standards is a group known as the International Digital Publishing Forum (IDPF), whose mission statement is to “foster global adoption of an open, accessible, interoperable digital publishing ecosystem that enables innovation.” <ref name= "IDPF"/> Many iterations of electronic publishing followed OEBPS; in 2007, the IDPF released ePub 2.0.<ref name= "IDPF"/> Constant updates to ePub occurred over the years, as can be seen to the right resulting in the current version, ePub 3.1, in 2017. It is anticipated that an ePub 3.2 will be released in the near future.<ref name= "Bit of History"/> | Electronic publishing came into the public view in 1999, through a format called the “Open eBook Publication Structure,” or OEBPS. <ref name= "Bit of History" >“A Bit of History.” EDRL Lab, accessed September 28, 2018. https://www.edrlab.org/epub/a-bit-of-history/ </ref> This format serves as a set of specifications for the “content, structure, and presentation of electronic books.” <ref name= "OEBPS"> “OEBPS (Open Ebook Forum Publication Structure) 1.2.” Library of Congress (2012). Last modified February 2012. </ref> Essentially, it is the set of standards required for electronic publishing. The body that selected the standards is a group known as the International Digital Publishing Forum (IDPF), whose mission statement is to “foster global adoption of an open, accessible, interoperable digital publishing ecosystem that enables innovation.” <ref name= "IDPF"/> Many iterations of electronic publishing followed OEBPS; in 2007, the IDPF released ePub 2.0.<ref name= "IDPF"/> Constant updates to ePub occurred over the years, as can be seen to the right resulting in the current version, ePub 3.1, in 2017. It is anticipated that an ePub 3.2 will be released in the near future.<ref name= "Bit of History"/> | ||

[[File:Timelineofepub.jpg]] | |||

[ | To be called an ePub, a file must contain certain features. These features include using dynamic markup and following a specific order when coding text, though the use of certain semantic markups. <ref name= "IDPF"/> ePub specifications also call for protection to rights and the creator, through what is known as Digital Rights Management (DRM). According to William and Mary Law School, DRM is a means to “prevent pirates from stealing and profiting from [others’] work” which in turn “encourages the creation of more content.” <ref name= "Dingledy"> Fred Dingledy, “What is Digital Rights Management?” Library Staff Publications (2016): 122 http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/libpubs/122 </ref> These features and specifications, along with others, help characterize ePub differently from other formats. | ||

==Components of ePub== | ==Components of ePub== | ||

Revision as of 19:28, 9 December 2018

TAC's ePub Page

Introduction

Books. Hardcover, paperback, scrolls...and ePub? Digital platforms and media continue to shape the world around us, and how one reads and experiences a book is no different. Society’s definition of what makes something a book continues to evolve and reshape over time. Gone are the days of curling up on the couch on a rainy day with your favorite book, the pages worn from frequent use and the spine cracked open to your favorite pages. Instead, you grab an electronic device, lacking any of the characteristic remarks of a physical book. The experience one has with reading a book changes. Moreover, what we call a book changes. One digital forum that allows for this aforementioned shift in definition is electronic publishing through ePub. This “eBook standard, designed to work consistently across multiple platforms, devices, and languages,” creates an experience with many similarities as well as differences to a physical book. [1]

What is ePub?

EPub by definition is a format standard for digitally based publications in addition to documents and other media using the “.epub” extension.[2] You can use ePub to create a product that is readable for the general public. It takes lines of code using markup languages, such as HTML or XHTML, and presents them as understandable text on a screen. Some common devices that support ePub with this reading include Adobe Digital Editions, iBook, Blue fire, and Aldiko. Electronic publishing came into the public view in 1999, through a format called the “Open eBook Publication Structure,” or OEBPS. [3] This format serves as a set of specifications for the “content, structure, and presentation of electronic books.” [4] Essentially, it is the set of standards required for electronic publishing. The body that selected the standards is a group known as the International Digital Publishing Forum (IDPF), whose mission statement is to “foster global adoption of an open, accessible, interoperable digital publishing ecosystem that enables innovation.” [2] Many iterations of electronic publishing followed OEBPS; in 2007, the IDPF released ePub 2.0.[2] Constant updates to ePub occurred over the years, as can be seen to the right resulting in the current version, ePub 3.1, in 2017. It is anticipated that an ePub 3.2 will be released in the near future.[3]

To be called an ePub, a file must contain certain features. These features include using dynamic markup and following a specific order when coding text, though the use of certain semantic markups. [2] ePub specifications also call for protection to rights and the creator, through what is known as Digital Rights Management (DRM). According to William and Mary Law School, DRM is a means to “prevent pirates from stealing and profiting from [others’] work” which in turn “encourages the creation of more content.” [5] These features and specifications, along with others, help characterize ePub differently from other formats.

Components of ePub

Materiality

Rights and Access

Aforementioned, DRM is a major distinguishing feature of ePub whose purpose is to protect the rights of a content creator so that work that unique work is appreciated as such. In essence, this prevents an individual from simply going online and copying the work of others or using the work of others in a manner not approved by the creator. Two central arguments can be drawn from Digital Rights Management, one with focus on the creator of content, and one with emphasis on consumers of eBooks. The first argument is that as society at large has increasing knowledge and access to the world wide web and all of the spaces available on it, those with some form of a computer coding or data-science background hold the capability to recreate an eBook or text. Whereas, in contrast, with a physical book you must either go rent or buy the book from a store or website to receive a physical copy with an “all-rights reserved” designation, on a digital platform, one could conceivably download or use a text in a manner outside of the author’s intended permission. The second, and contradicting, argument is that by limiting access to the general public, there is an attempt to limit “user choice and innovation.” [6] Furthermore, antagonists of DRM argue that no substantial evidence shows DRM preventing “copyright infringement” and “[keeping] consumers safe from viruses.” Today, there exist organizations such as Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), which aims to protect the rights of human privacy while “[preserving] fundamental rights,” and Project Gutenberg, whose mission is to “encourage the creation and distribution of eBooks” by serving as the “first provider of electronic books.” Expanding on this concept presented by Project Gutenberg and EFF, specific questions arise regarding the social aspects associated with an ePub versus a physical book. Personally, book sharing through the library and with friends remains a central part of my childhood memories. I loved visiting the librarians who knew me by name and discovering an exciting new book to learn from. With the restrictions that exist with ePub, one can no longer hand over a great read to a friend or talk to the librarian as he or she stamps the return date into a book. With DRM, this ease in accessibility and social interaction is in a sense removed, altering the dynamic one has with a book. As the notion of access as it relates to books has and continues to change as books move more and more towards the digital, one is left wondering about how far rights and access extend from concepts such as DRM. Next, we will see an example of this extension.

Conclusion

Notes

- ↑ Galey, A. “Enkindling Reciter,”Project Muse 15 (2012): 210-247

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 IDPF. “ePUB Specifications and Projects.” Last modified April 2018. http://www.idpf.org/epub/dir/

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 “A Bit of History.” EDRL Lab, accessed September 28, 2018. https://www.edrlab.org/epub/a-bit-of-history/

- ↑ “OEBPS (Open Ebook Forum Publication Structure) 1.2.” Library of Congress (2012). Last modified February 2012.

- ↑ Fred Dingledy, “What is Digital Rights Management?” Library Staff Publications (2016): 122 http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/libpubs/122

- ↑ DRM.” Electronic Frontier Foundation, accessed October 13, 2018.[1]