Collection of American Friendship Album Resources: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

=== What the LCP Album Project Offers === | === What the LCP Album Project Offers === | ||

The project is organized into sections discussing different aspects of the text: the digital copies of the albums themselves, history & materiality, and illustrations. Additionally, clicking on the “Collection” option under the Albums tab redirects to the Library Company’s collection for that specific album. Here, the digital pages of the albums are displayed accompanied by relevant metadata (date of composition, the owner, names of the contributors, what the volume is made out of, etc.). <ref name= "Four" /><ref name= "Five" /><ref name= "Six" /> | The project is organized into sections discussing different aspects of the text: the digital copies of the albums themselves, history & materiality, and illustrations. Additionally, clicking on the “Collection” option under the Albums tab redirects to the Library Company’s collection for that specific album. Here, the digital pages of the albums are displayed accompanied by relevant metadata (date of composition, the owner, names of the contributors, what the volume is made out of, etc.). <ref name= "Four" /><ref name= "Five" /><ref name= "Six" /> On the home page, there are two additional features: “Experience the Events” and “Trace Their Steps.” “Experience the Events” catalogues the timeline of additions to the Cassey Album and the movement of the contributors, offering a closer look into how the movement of nineteenth century Black intelligentsia influenced the textual quality of the album and, on a broader scale, nineteenth century literary cultures. For example, [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_McCune_Smith| James McCune Smith], an African American doctor and [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abolitionism_in_the_United_States| abolitionist], wrote the poem “To the River Clyde” on page 39 in the Cassey Album after returning from Scotland in 1833.<ref name= “Seven”> [https://lcpalbumproject.org/?page_id=166| "Events."] ''Philadelphia Library Company.'' Retrieved 28 Nov. 2020. </ref> “Trace Their Steps” is supposed to show the location of events and the homes of the contributors; unfortunately, as of the time of writing, the map function on "Trace Their Steps" is non-operational.<ref name= "Eight"> [https://lcpalbumproject.org/?page_id=81| "Map." ''Philadelphia Library Company.'' Retrieved 28 Nov. 2020. </ref> | ||

On the home page, there are two additional features: “Experience the Events” and “Trace Their Steps.” “Experience the Events” catalogues the timeline of additions to the Cassey Album and the movement of the contributors, offering a closer look into how the movement of nineteenth century Black intelligentsia influenced the textual quality of the album and, on a broader scale, nineteenth century literary cultures. For example, [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_McCune_Smith| James McCune Smith], an African American doctor and [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abolitionism_in_the_United_States| abolitionist], wrote the poem “To the River Clyde” on page 39 in the Cassey Album after returning from Scotland in 1833.<ref name= “Seven”> [https://lcpalbumproject.org/?page_id=166| "Events."] ''Philadelphia Library Company.'' Retrieved 28 Nov. 2020. </ref> “Trace Their Steps” is supposed to show the location of events and the homes of the contributors; unfortunately, as of the time of writing, the map function on "Trace Their Steps" is non-operational.<ref name= "Eight"> [https://lcpalbumproject.org/?page_id=81| "Map." ''Philadelphia Library Company.'' Retrieved 28 Nov. 2020. </ref> | |||

=== Collection Drawback === | === Collection Drawback === | ||

Revision as of 23:28, 29 November 2020

During the early nineteenth century, friendship albums rose to popularity in the United States of America, especially among young women. Friendship albums are bound, often ornate volumes that an individual would entrust to a friend who would then inscribe inside the album; these inscriptions varied, including poetry, long essays, water color paintings, and short stories.[1] The rise in this particular form of nineteenth century print culture is due in part to the rise of sentimentalism in literary cultural practices. Sentimentalism as a philosophy is rooted in the idea that people can form meaningful relationships and build communities through the effort of empathy.[2] This Wikipedia page looks specifically at two digital resources for studying American friendship albums: the Cassey & Dickerson Friendship Album Project and the Mary Wallace Peck Mansfield Album.

Cassey & Dickerson Friendship Album Project

The Cassey & Dickerson Friendship Album Project is an online exhibit curated by scholars working for and with The Library Company of Philadelphia. The Amy Matilda Cassey Album, the Martina Dickerson Album, and the Mary Anne Dickerson Album, are some of the Library Company’s most requested items, making the digital exhibit an invaluable resource in the study of material cultures.[3]

A Closer Look at the Albums

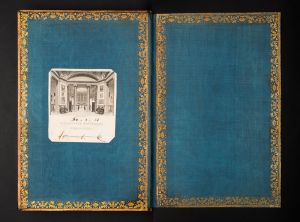

The physical albums are ornate and expensive volumes. The covers are made of Morocco bindings, an expensive leather made from goatskins, that are embossed and gilt, creating intricate patterns in the leather material that are further decorated with gold.[4] [5] [6] As an additional decorative touch, the Cassey Album has blue moiré silk doublures, ornamental linings on the inside of a book.[4] The blank album that would become Mary Anne Dickerson’s was published in New York and contains 81 leaves, seven plates, and four illustrations; the blank album that would become Martina Dickerson’s was published in London and contains 95 leaves and four drawings; and lastly, the blank album that would become Amy Matilda Cassey’s has 76 leaves, 10 drawings, and the publishing location is still unknown.[4][5][6]

Cassey and the Dickersons were middle-class African American women of the mid-nineteenth century actively involved in the Black anti-slavery communities as well as the Black elite intelligentsia; their contributors were fellow community members and abolitionists in major northeastern cities like Philadelphia, New York, Boston, and Baltimore.[4][5][6] In the case of the Cassey Album, there are many contributions from both white and Black well-known abolitionist figures, such as Fredrick Douglas, William Lloyd Garrison, and Lucy Stone.[4] The Cassey and Mary Anne Dickerson Albums received contributions starting in 1833, with Martina Dickerson’s contributions starting a little later in 1840. The contributions to the Martina album stopped the earliest in 1846 ten years prior to the last Casey Album contribution in 1856. Interestingly, the Mary Anne Dickerson Album continued being circulated and receiving contributions until 1882, even though Mary Anne herself died in 1858. This metadata shows how friendship albums are authored by communities and collectives, replicating the goals of sentimentalist philosophy.[4][5][6]

What the LCP Album Project Offers

The project is organized into sections discussing different aspects of the text: the digital copies of the albums themselves, history & materiality, and illustrations. Additionally, clicking on the “Collection” option under the Albums tab redirects to the Library Company’s collection for that specific album. Here, the digital pages of the albums are displayed accompanied by relevant metadata (date of composition, the owner, names of the contributors, what the volume is made out of, etc.). [4][5][6] On the home page, there are two additional features: “Experience the Events” and “Trace Their Steps.” “Experience the Events” catalogues the timeline of additions to the Cassey Album and the movement of the contributors, offering a closer look into how the movement of nineteenth century Black intelligentsia influenced the textual quality of the album and, on a broader scale, nineteenth century literary cultures. For example, James McCune Smith, an African American doctor and abolitionist, wrote the poem “To the River Clyde” on page 39 in the Cassey Album after returning from Scotland in 1833.[7] “Trace Their Steps” is supposed to show the location of events and the homes of the contributors; unfortunately, as of the time of writing, the map function on "Trace Their Steps" is non-operational.[8]

Collection Drawback

The albums are grouped together as they all belonged to African-American middle class women of the nineteenth century, though more is known about Amy Matilda Cassey than Mary Anne and Martina Dickerson. This is reflected in the unequal amount of metadata available for each album with the most information being devoted to the Cassey Album and the least on the two Dickerson Albums. For example, in addition to offering a page-by-page browse through the original entries in the Cassey Album, there’s also page-by-page transcriptions and analysis. [9] Only the Cassey Album and the Mary Anne Dickerson albums have entries on the “Illustrations” page showing the many different intricate watercolor paintings contained in all three albums; of these, the Cassey Album is once again the only text that also has accompanying transcriptions or interpretive text. [10] All of the people represented on the Contributors page are contributors to the Cassey Album.

Mary Wallace Peck Mansfield Album

The Mary Wallace Peck Mansfield album is digitally archived on "The Ledger," a database of students of the Litchfield Law School and the Litchfield Female Academy conceived by the Litchfield Historical Society. In contrast to the Cassey & Dickerson Albums, Mansfield’s album circulated much earlier in the 1800s, from 1825 to 1826 and did not circulate in many different cities.[11] As is the case with friendship albums, the circulation and types of contributors is closely connected to the creator’s community. Mansfield studied at the Litchfield Female Academy starting from 1811 to 1817 and in 1825 taught drawing at Sara Pierce’s Academy.[11] Contributors include members of the Reeve, Beecher, and Wolcott families as well as female academy and law school students, and the types of contributions include hair memorials, poetry, letters to loved ones, and watercolor paintings.[12]

References

- ↑ Jennifer Blouin. Article 5: Eternal Perspectives in Nineteenth-Century Friendship Albums. The Hilltop Review, vol. 9, pp. 63-76 (2016), Retrieved 28 Nov. 2020

- ↑ Mary G. De Jong. Sentimentalism in Nineteenth-century America : Literary and Cultural Practices. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, pp. 8-18 (2013), Proquest Central Complete, Retrieved 28 Nov. 2020.

- ↑ "Cassey & Dickerson Friendship Album Project." Philadelphia Library Company. Retrieved 28 Nov. 2020.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 "Amy Matilda Casey Album" Philadelphia Library Company. Retrieved 28 Nov. 2020.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 "Martina Dickerson Album" Philadelphia Library Company. Retrieved 28 Nov. 2020.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 "Mary Anne Dickerson" Philadelphia Library Company. Retrieved 28 Nov. 2020.

- ↑ "Events." Philadelphia Library Company. Retrieved 28 Nov. 2020.

- ↑ [https://lcpalbumproject.org/?page_id=81%7C "Map." Philadelphia Library Company. Retrieved 28 Nov. 2020.

- ↑ “Casey Album, Table of Contents|LCP Album Project” Philadelphia Library Company. Retrieved 28 Nov. 2020.

- ↑ “Illustrations|LCP Album Project’’ Philadelphia Library Company. Retrieved 28 Nov. 2020.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 “Litchfield Ledger - Student” Littchfield Historical Society, Retrieved 29 Nov. 2020

- ↑ “Litchfield Ledger - Object” Litchfield Historical Society, Retrieved 29 Nov. 2020