Chapters

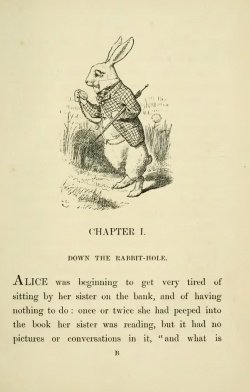

The chapter, which has become synonymous with the modern-day novel, left a lasting impact on book history. Nowadays, chapters are found in virtually every form of text. They can be found in fiction and story books, non-fiction novels, as well as informative works such as textbooks and cookbooks. Depending upon the author and purpose of the text, each chapter might be outlined in a table of contents at the beginning of the novel and have its own title. Some novels, such as those in the Harry Potter series, also have a small illustration at the beginning of each chapter that depicts a scene in the upcoming section; this in a sense gives each section its own title page. Some chapters even become incredibly iconic and are instantly recognizable by readers like "Down the Rabbit-Hole": the first chapter from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. Chapters also give authors another way to add more creativity into his/her work, and some choose to integrate special attributes that generate a unique reading experience for his/her audience. And yet, in some books it seems as if chapters do nothing more than simply create installments; some authors opt to just use numbers to begin each chapter. Though in modern times chapters can take all sorts of forms and be found in all types of writings, this has not always been the case. Initially, chapters could only be found in non-fiction and informative works; their purpose was to make navigation within large text easier. And yet, its simple origin as a better way to find and reference information ultimately altered our reading culture from one of long, continuous reading to one oriented around pauses. In essence, the chapter has evolved from a teaching tool to a stylistic device that has greatly influenced the development of our society’s reading habits.

Origin

Despite what one might assume, the idea of dividing text emerged centuries before the codex. The first signs of a chapter-esque system existed in writings from the 1st century: 200 years before the codex replaced the scroll as the dominant platform. In modern day, most people associate the chapter with narrative; necessary for the shifting of scenes in a story.[1]. And yet, storytellers were not even the first individuals to utilize this newborn technology. In fact, it was intellectuals and scholars who used chapters first as a method to divide their large manuscripts full of knowledge into smaller segments. With this, readers feel less overwhelmed by the immense amount of knowledge present in the text, and have a better opportunity to fully understand the information they are presented. However, chapters served a greater purpose than simply dividing the book into sections: they acted as reference points that made finding specific information in these long text easier. Both of these functions of chapters are continually used in modern day textbooks. For example, introductory-level biology textbooks cover a huge breadth of information, but only certain sections usually pertain to the particular topic taught in class. More often than not, individuals would not read all 900+ pages of a textbook just to learn about cell organelles or ecology specifically. Rather, readers would go straight to the portion of the book distinctively concerning the material relevant to the class lesson. Early scholars understood this and realized that readers would consult their works, not read continuously through them like a narrative. They understood that their audience were fellow intellectuals who also desired to acquire knowledge. Chapters create this system of reading. Chapters break up this information into more approachable parts, and allow readers to easily choose which sections they want to read based on what they want to learn. This, in conjunction with other paratexts such as page numbers and footnotes, made navigating through this sea of information much easier.

As stated, the idea of a divisional system to separate text into smaller portions can be seen in many scholarly works prior to the transition of the scroll to the codex in the 4th century. Books from the 1st and 2nd century, such as Pliny The Elder’s Naturalis Historia and Aulus Gellius’s Noctes Atticae, employ such. In both instances, the authors divided their works into different bits called “liber”, which is latin for “book”. Though each of these portions contributed to an over-arching idea, they all contained dissimilar information. These writings touched upon a variety of topics relating to zoology, botany, ethnography, anthropology, astronomy, history, philosophy, and even simple everyday observations. Understandably, not all of these distinct subjects might be relevant to an individual's intellectual inquiries. By utilizing these chapter-esque methods, Pliny the Elder and Aulus Gellius have given readers the ability to more easily locate specific sections. Furthermore, below the "Liber" number it can be seen that these early scholars also further segmented the individual "libers" into smaller parts using roman numerals. Similarly, both text begin with an index that outlines the contents of the work and their locations within the physical book. The combination of both of these additional features makes it even easier to find the location of certain information with greater specificity and precision. With this, the audience can read the particular portions pertaining to their academic agenda without having to gloss through the entire text. These scholarly works laid the ground work for this new technology to become the division system modern society is accustomed to.

Chapters and Christianity

Reading entire passages to locate one relevant scene or quote was incredibly inefficient which made narratives significantly more difficult to learn from. “Indicat[ing] very precisely where… quotations [could] be found” or at what physical part of a scroll particular events existed was hard given many of these long, continuous passages of text had no division or reference system [2]. This only became increasingly inconvenient as uniform, mass-production did not exist and “no rules governing the length of lines or the number of lines to a column” existed for scroll manufacturing [3]. One can see this on the scroll version of the Book of Esther: a book in the third section of the Christian Old Testament and one of five scrolls in the Hebrew bible. Though there seems to be divisions based on the layout of writings, the scroll itself was still simply a long text on a leather parchment. No markers or reference points of any kind exist. This makes finding any particular moment more tedious and difficult if one isn't familiar with the holy writing. This also forces individuals to remember the physical location of the portions on the roll they wished to cross-reference in the future. Doing so is even more troublesome given the immense length of the substrate as well as the vast amount of content it contains. This also makes referencing quotes and lines from this scroll in other writings difficult: no markers or referencing tools exist for writers to mention, and for readers to identify and look for.

Christian scholars acknowledged the difficulty in using narratives for educational purposes. Scholars wrote down the whole message God gave them so that future readers could also get the whole message and not just a couple segments [4]. Gospel stories, thus, were written continuously, undivided, and unlabeled which caused great frustration when trying to teach from them. Deriving the idea from informative text like those written by Pliny and Gellius, Christian scholars adopted the idea of chapters into the bible. This new, physical evolution of the testament became the signature technique of the gospels. But more importantly, this transition exists as the first time the idea of chapters and text division was implemented into narrative writing.

Eusebius developed the first method to divide the bible in the 3rd century. Eusebius’ system was very simple. Essentially, he divided the gospels into many small sections each marked by a number and a letter in the margins. A table of reference called the Canons at the beginning of the manuscript identified these sections and their relation to the other gospels in the narrative [5]. However, many other scholars also attempted to divide the gospels in their own way, and thus the divisions of the bibles that first adopted the chapter systems varied drastically. However, these conflicting ideas on how to divide the bible is understandable given the subjectivity involved in segmenting a story. Scholars can easily organize information based upon how the topic and concepts within the book relates to one another. However, there is no objective way to determine what counts as a significant moment in a story deserving of its own section, and where one installment should start and end. Because of this, "almost each Bible had its own particular division" [6]. It would take some time before a universal division system emerged for the testament, and by the end of the 12th century there were thousands of different systems of division in use [7].

However, “[society] owes to Stephen Langton [the] division of” the modern-day bible [8]. The system “successfully started by Stephan Langton [in the 13th century] had such a lasting impact”, and over time it developed into the biblical one used today [9]. He created longer, less frequent divisions that clustered events into chapters based on time and place rather than focusing on getting these events to run in parallel. In any case, though chapters now existed in a narrative environment, their purpose still remained the system as if it was in an informational one: a way to easier reference and locate certain sections. With chapters, referencing certain events during Gospel teachings became effortless as individuals could easily locate passages without having to skim through other parts of the testament to find them. This in conjunction with the addition of verses allows even greater specificity, making even referencing lines a didactic possibility [10]. This signified a shift of reading practices from one revolving around over-arching concepts to one revolving around remembering fragments. Since chapters allowed readers to choose which parts they wished to read, it became much easier to pick out sentences that particularly stuck with them. This created much controversy as individuals such as John Locke believed such divisions presented a considerable risk of obliterating the powerful coherence of the Word of God [11].

Moreover, this created new possibilities in subsequent writing practice. The ability to easily navigate the bible allowed the authors to reference of quotes and scenes in their own writings; this generated greater authenticity and made points and arguments more convincing. Since the bible represents the word of god, this essentially made scholarly text that cited the bible both more powerful and more authoritative. The general theme of a gospel diminished in importance, and the individual lines became more significant as these could be cited and referenced; these were considered the direct words of god. Given its immense influence in European society, the Church had an undeniably significant role in transitioning chapters into narrative text. The idea of chapters might have disappeared and been replaced by another form had the Church not adopted it as the signature technique of the bible.

Increasing Ubiquity and Initial Transition into Common Literature

As this new idea of chapters began to become more recognized in the 14th to 15th century, scholars started to insert them into other texts for teaching/referencing purposes. The chapter's transition into common literature mirrored its slow addition into the bible: it was initially awkward given they were designed for locating information within a text. Chapters continued to function primarily in didactic environments, and their presence in literary works were still geared towards an academic audience. They evinced a type of reading revolved around taking notes and understanding events in the context of the novel. They created a focus on referencing and learning from specific plot points and passages rather than over-arching concepts. For example, William Caxton divided the iconic “Le Morte d’Arthur” into 21 divisions each with its own set of chapters in his 1485 edition. This gave readers the ability to more easily choose which moments of the story could be applied to certain teachings. Not only did William Caxton add divisions for easier referencing, but he added summaries to the beginning of the novel for each one. With this, readers could “understand briefly the content of this volume” without having to read the entire book [12].

This further supports the idea that chapters are meant for a didactic setting and a focus on learning from specific events. These summaries allow readers to analyze how specific moments relate to themes and morals present in the narrative without having to actually read the entire novel. Caxton essentially gave his audience the ability to choose from which moments the audience wished to learn from.

Modern-day Utilization

As time progressed, the chapter did not undergo much change. Though the average length of the chapter did increase, it slowly became another aspect of the novel that was simply expected rather than have any sort of significance. Understandably, society had become accustomed to these divisions because of their increased presence within literature. However, in modern-day authors have started to utilized novels in a way to create unique qualities in their works. In a sense, these authors became more like artist and use the chapter to express and create different meanings and experiences for the viewer.

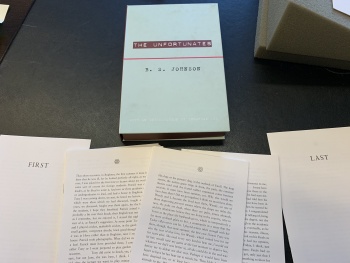

One example of this is adventure or “pick your path” books. Adventure books start with chapter one but differ from conventional novels in that each chapter ends with a “now what do you decide to do” scenario. The reader gets to choose the actions of the character and depending on what he/she decides to do, the book instructs he/she to go to a certain chapter and this goes on until the ending. This means chapters are like levels of a video games in a sense. Furthermore, a specific piece of literature that utilizes a similar ideology is The Unfortunates by B.S Johnson. This novel came in a box with 27 separately bound chapters. Only a first and last chapter is specified, and thus the chapters can be read in any order the audience pleases. In both cases, the use of the chapter strays from its traditional purpose of referencing and citation. These artists are using chapters in a way which emphasizes how the chapter's divisional function can directly affect the narrative. These artists made a more interactive experience, and essentially gave the readers the power to author their own story by giving them control over the individual installments. This increased customization in novels is tailored to an audience that wishes to have the power to create what they want to read. It evinces a type of reading that forces the audience to become immerse in the story. In the case of adventure books, the reader even has a direct impact on the narrative thread, literally taking the role as the protagonist and making decisions that govern the course of the novel. In both cases, readers become involved in the making of the story. Authors also use chapters to create stories with unique reading experience. This can be seen in both Hopscotch by Julio Cortazar and Flipped by Wendelin Van Draanen. In Hopscotch, readers can proceed through the novel normally, or a table of instructions offers a special way to read the novel that creates a second story. Flipped on the other hand is simpler, in that after each chapter, the narrator switches from the perspective of the male protagonist to the female protagonist. This special quality allows the audience to hear both sides of the story: two different voices which give a broader perspective on the events of the novel.

Opinions of Chapters

Chapters not only transformed how texts conveyed and organized information, but it also gave authors another aspect of the physical book to toy and play around with. However, the greatest effect of the introduction of chapters into narrative writing relates to how it influenced society’s modern day reading habit. As Laurence Sterne said, chapters created a reading culture oriented around pauses. Chapters gave individuals the ability to immerse themselves and incorporate novels into their everyday routines. No longer did people have to dedicate entire days to finish an entire book; reading at such an intensity unimaginable by our society's standards [13]. In the world's current fast-pace society, where finding any sort of pleasure time is difficult, this particular aspect has become increasingly more important. A chapter can be read before bed, after one wakes up, on a lunch break, or really anytime someone has a little bit of free time. This draws a parallel between books and TV series. Like episodes of a series, individuals can squeeze singular chapters into their busy schedule. But most importantly, chapters made installments that “relieve the mind” [1]. The breaks that chapters create encourage readers to pause and think: to truly reflect and ruminate after events of a passage.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Sterne, Laurence, and Douglas Grant. Sterne: Memoirs of Mr. Laurence Sterne; The Life & Opinions of Tristram Shandy; A Sentimental Journey; Selected Sermons and Letters. Harvard University Press, 1970.

- ↑ Banning 2007, Reflections upon the Chapter Division of Stephan Langton, pg. 149 .

- ↑ Ackroyd 1992, The Cambridge History of The Bible, pg. 51 .

- ↑ “Eusebian Canon.” Eusebian Canon (Full Story) - Early English Bibles, [2].

- ↑ Banning 2007, Reflections upon the Chapter Division of Stephan Langton, pg. 147 .

- ↑ Banning 2007, Reflections upon the Chapter Division of Stephan Langton.

- ↑ Banning 2007, Reflections upon the Chapter Division of Stephan Langton, pg 142.

- ↑ Banning 2007, Reflections upon the Chapter Division of Stephan Langton, pg 159.

- ↑ Chapters and Verses—Who Put Them in the Bible?” Jehovah's Witness, www.jw.org/en/publications/magazines/watchtower-no2-2016-march/bible-chapters-and-verses/.

- ↑ Finkelstein, David. The Book History Reader. Routledge, 2010, pg 52.

- ↑ Malory, Thomas, et al. Le Morte D'Arthur / The Original Edition of William Caxton Now Reprinted and Edited with an Introd. and Glossary ; by H. Oskar Sommer ; with an Essay on Malory's Prose Style by Andrew Lang. D. Nutt, 1891.

- ↑ Finkelstein, David. The Book History Reader. Routledge, 2010, pg 21.