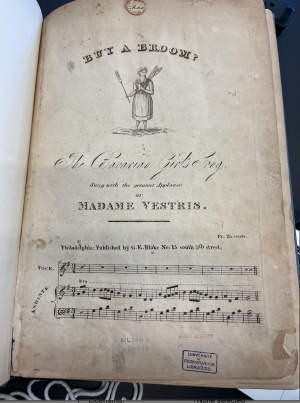

Songs; Collections of American sheet music bound into volumes by their original owners between 1820 and 1860

Songs is an anthology comprised of two bound collections of sheet music for keyboard and voice produced primarily by early American music publishers. Largely representing music printers from prevalent early American cities such as Philadelphia, New York, and Baltimore, the set also contains two works printed in Milan. The collection was originally compiled from an otherwise-unidentified Mrs. Hudson, who lived in a time contemporary with the active period of the printers featured within the books. The collection later passed into the hands of a similarly-unidentified I. Micle, who gifted the anthology to the University of Pennsylvania in 1942. Songs was then accessible through the University's Music Library before being relocated to the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts, where it currently resides.

Early American Music Printing

Development of Music Printing Systems

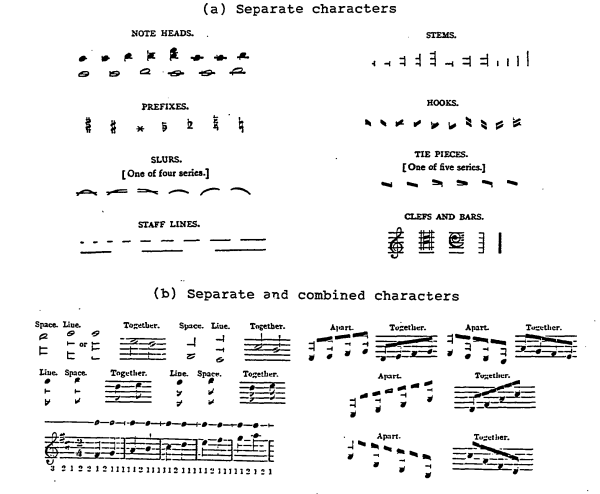

Prior to the 19th century, ink printing of all varieties were often dominated by the usage of moveable type (in which type could be set in an order to create coherent ideas when inked), woodcut (where a desired image was cut out of a piece of wood to create a raise surface for ink to rest on), and intaglio (where a desired image was carved into a metal plate such as copper, where ink could well up).[1][footnotes 1] Moveable type was particularly effective for the transcription of written language, while woodcut and intaglio were preferred for image creation. Western musical notation, however, fell in a space between these two categories, which posed issues for a system created with the intention of an alphabet separate from images. Although featuring regularity of note images, the placement of these notes in a 5-bar staff and the connection of these notes via "beaming" prevented the system from easily being replicated piecewise, as moveable type would do, while simultaneously being time-consuming to recreate by hand.

Colonial Era and 18th Century Printing

Printing in this time had not yet developed beyond either moveable type or hand-engraved intaglio; type printing from this time, therefore, requires an enormous quantity of castings to capture the thousands of possible combinations of notes, dynamics, articulation, and phrasing markings.[footnotes 2] Intaglio marking was done entirely by hand, and although objectively more difficult to read, was prized for individualized expression of the music by the printer's own hand.[footnotes 3]

Engraved Printing in the 19th Century

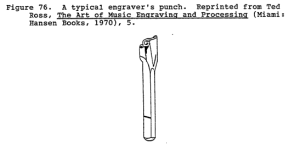

Music printing was revolutionized in 1787 by silversmith John Aitken, who developed a method of merging the spirit of the moveable type with the clearer image associated with intaglio.[footnotes 4] Pewter (rather than the more expensive copper) plates, pre-engraved with staff lines, would be "punched" with musical symbols, enabling a lesser amount of punches (analogous to type), while maintaining continuity of lines across the staff, and the greater definition of lines afforded by intaglio.

While this method was quickly taken up by secular music printers, such as early American printing giants George Blake and George Willig[footnotes 5], printers of sacred texts tended to continue using the type-set method.

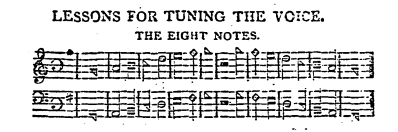

Shape-Note Notation

Early American music is well-known for developing the innovative, but ill-fated, concept of the shape-note. Using this Western notation-derived concept, note heads on the staff would have a different shape corresponding to their sound in the European solfege system (e.g. do, re, mi). William Little, the first printer to use this notation, is commonly thought to be the founder of this type of musical printing.[footnotes 6] While this method limits expression of music using the shape-note format to very tonal Western sounds, it was nonetheless a vital tool to teach Americans with a lower level of arts education to sing popular tunes and hymns. From a printing perspective, this method required even more type sorts, since new type would also be required to represent every different note head used in the system. This method has fallen out of favor to notate pitch, but lives in on percussion notation, where different noteheads denote different percussion instruments.

Early American Printers

Many of the music printers featured within this collection were the largest printers of their time period.

- George E. Blake (1775-1871), advertised in 1803 as owning the Americas' largest music collection, lived above fellow printer John Aitken's printing shop and taught flute and clarinet, before he took own his own shop in 1802. He published secular music, as did most of the printers within this collection, and used the punched-intaglio style that developed following 1787. [2]

- Aitken, by contrast, was a silversmith by trade, not a musician; as a result, he had developed an early start in the music printing and was the first to utilize punched engraving, but was soon out-competed by newer printers who were musicians as well as printers (eg. John Christopher Moller, Henri Capron, and Benjamin Carr). [3]

Benjamin Carr - George Willig, in addition to developing a large musical printing network by himself, was one of the first publishers to develop a family trade of printing. All the above printers were all Philadelphia-based, but Willig's son, George Willig Jr., spread the business via a Baltimore branch taken over from the brother of another famous American printer, Benjamin Carr. [4]

- Benjamin Carr was a London-born printer who was active in Philadelphia and Baltimore, alongside his brother, Thomas. Benjamin Carr is specifically of interest for this collection because the anthology contains a score handwritten for the original owner by Benjamin Carr (the only score in the collection to be featured so). [5]

- Fiot and Meignen were a pair that published music, that arose following the period dominated by the above printers. They were a dominant printer in Philadelphia until their dissolution in 1839, which prompted Meignen to print on his own until 1859, still remaining dominant. [6]

- John Cole was a Baltimore publisher, and the first to use pictograms on the front page of the scores to advertise them (much like in the style of broadside ballads)[7]

The Collections

Structure

Organization

The collection is comprised of many different, originally loose-leaf scores, bound into two codices. Using dating by the active periods of the publishers, the scores enclosed are organized in roughly chronological order. For example, the bound first book of the collection has many prints from G. Willig, where the second book features more from the workshop of G. Willig Jr. This implies a linear temporal relationship as one reads through the volumes. Unlike the codices that this book resembles, it cannot be easily categorized into folio, quarto, etc. since the gathering of leaves are variant based on the length of each individual score, as well as the spacing used by different printers. Given its nature, this book also does not feature a foreword, index, or any other contextualizing paratexts. However, several cards were included with the codices which provide reference to some of the individual scores, which appear to be part of a card catalog used during this anthology's time in the University of Pennsylvania Music Library. There is no other navigational tool, such as a table of contents, that appears within the book. These cards are labelled with the Dewey Decimal System of classification for nonfiction, which again alludes to the book's use as reference or resource in the University of Pennsylvania Music Library.

Design

Both codices are of similar size; the first features a blue cover with "Songs" embossed in gold; the second is the same, but in black. These books lack own original binding; this can be seen from the fact that the set was donated as anthology to the University in 1942; however, the pastedown of the first book's front cover is labeled 1951, indicating rebinding. This is further reinforced by the fact that the current binding on the book is comparable to hardcovers found within the University's music library to this day, indicating at some point an interest from members of the University to standardize the size, shape, or appearance of books within the University collection.

The book also has clearly undergone repair beyond a rebinding; there are multiple instances where pages that have been torn (presumably from page turns or other rapid motion) have been sewn back together. This indicates a degree of care for the score/scores in the collection.

In order to standardize the sizing between scores, the edges have been regularly cut such that each score now has the same dimensions. It is clear that this is the case, rather than standardized page sizing in the Americas, because in many cases the identifying name "Hudson" is partially cut off at the top.

Almost all of these scores, with the exception of one, use the highly popular punched, intaglio printing, as evidenced by the imprint of metal plating on each page. Lithography, the primary music printing tool in later 19th century, was not yet prevalent[footnotes 7]. The pages are all made of paper, which has no clear grain and is generally smooth.

Content

Not all works had legible titles or were fully identifiable, but the entire collection featured printed scores for keyboard and voice from these music publishers at these locations (as listed on each score):

Philadelphia:

- Philadelphia: G.E. Blake No: 13 South 5th Street

- Philadelphia, Printed for B. Carr

- Philadelphia Published by G. Willig 171 Chestnut Street

- Philadelphia, Fiot, Meigen and Co

- Philadelphia Published by John G. Klemm

- Philadelphia John F Nunns, 70, South 3rd Street

New York:

- New York: Dubois and Stodart at the Piano and Forte Music Store No 126 Broadway

- New York: Dubois and Stodart No 167 Broadway(Sold by Fiot, Meigen and Co)

- New York Published by Hewitt and Jaques, 239 Broadway (sold by G Willig)

- New York, Published by E, Riley, 29, Chatham St (sold by G Willig)

- New York, Pubs by Firth and Hall, 1 Franklin Square (3)

- New York; Published by A Bagioli, Broadway, (sold by Fiot, Meignen, and Co)

Others:

- Baltimore Published by John Cole

- Baltimore: Published and sold by G. Willig Jr (Sold by JF Nunns)

- Boston, Published by C. Bradlee Washington Street

- Published G. Ricordi dirimpeto all I R Teatro Alla Scala, Milan

It is worth noting that "song" refers to music with lyrics and accompaniment, meant to be performed by voice and accompaniment. The liberal understanding of "song" used today does not necessarily fit this context, but at the period contemporary with the printing of the scores and binding of these books, this was the case.

Usage

As Music

It is clear from the numerous annotations and marginalia made within the score that these scores were both made and used for musicmaking. For example, the following image shows a written-in new set of notes to be performed over what was printed, indicating thought from a performer/owner on how they would like to personalize the piece during performance.

These kinds of additions, as well as markings such as carets, arrows, etc. are all classic notations used to annotate music for study and performance. The recurrent writing of the name "Hudson" on every score indicates a strong sense of single ownership; Hudson is known to be the original owner since there are works that are created individually for her, such as one hand-printed by Benjamin Carr.

It is heavily implied from the place of origin of these scores that the original owner was a Philadelphian, as most of the scores sourced from other cities were stamped as being resold at a Philadelphia location.

As Reference and Collectible

As traced from marginalia on the front page, this collection made its way into the hands of the University of Pennsylvania Music Library, which made markings for the sake of categorizing and organizing the books. For example, the University Music Library placed their own bookplate onto the pastedown of the books, as well as stamps on the first pages to mark their own property.

The fact that the books were bound at all, especially the haste with which they were bound, indicates a lack of interest in using the music to perform, as opening the book wide is very hard and tests the bindings significantly. This makes performance difficult due to lack of visibility and simple page turns when playing at the keyboard. This marks a shift in understanding from the scores as viable forms of performable art to consideration as a collectible, comparable to the preservation of ephemera. While the prints are better made than, for example, the broadside ballad, they were clearly made quickly and mass produced, as evidenced by ink bleeding across pages within each score (a telltale sign if insufficient time left to dry before stacking). This shift in understanding of the collection is further compounded by the book's transfer into the Kislak Center from the Music Library. The books are now no longer intended to be used as a musical reference, but as a historical/biblographical reference instead.

Notes

References

- ↑ Mayo, Maxey H (1988). Techniques of music printing in the United States, 1825-1850 (MMus). University of North Texas.

- ↑ Bewley, John. Philadelphia Music Publishers: George E. Blake (1775-1871). University of Pennsylvania Library's Department of Special Collections. Retrieved on April 7, 2023.

- ↑ Bewley, John. Philadelphia Music Publishers: John Aitken (1744 or 1745-1831). University of Pennsylvania Library's Department of Special Collections. Retrieved on April 7, 2023.

- ↑ Bewley, John. Philadelphia Music Publishers: George Willig (1764-1851). University of Pennsylvania Library's Department of Special Collections. Retrieved on April 7, 2023.

- ↑ Bewley, John. Philadelphia Composers and Music Publishers: Benjamin Carr (1760-1831). University of Pennsylvania Library's Department of Special Collections. Retrieved on April 7, 2023.

- ↑ Bewley, John. Philadelphia Composers and Music Publishers: Leopold Meignen (1793-1873). University of Pennsylvania Library's Department of Special Collections. Retrieved on April 7, 2023.

- ↑ MUSIC STORES AND PUBLISHERS Johns Hopkins University Lester S. Levy Collection of Sheet Music. Retrieved on April 7, 2023.