Paper

Print as Liberatory Practice: An Analysis of Early African-American Press Through The Crisis

Be it enacted…that any free person, who shall hereafter teach, or attempt to teach, any slave within the State to read or write, the use of figures excepted, or shall give or sell to such slave or slaves any books or pamphlets, shall be liable to indictment in any court of record…

-Act Passed By the General Assembly of the State of North Carolina at the Session of 1830-1831

Introduction & Historical Background

Less than 100 years after this now infamous law was cemented into the Unites States judicial system, African-American scholars and lay-folks alike had completely reclaimed their relationship to the act of literacy. In a postbellum United States landscape, they made conscious and pragmatic moves to explore popular canonical genres of American letters—such as magazines and periodicals—and transform them into tools of liberation in form and purpose. Through material and bibliographic analysis of The Crisis, the first Black owned and operated magazine in the United States, this page aims to unpack the ways in which a collective network of Black scholars (NAACP affiliated and otherwise) came together to use paper as a physical substrate to argue for the legitimacy of Black press.

To be clear, this analysis does not discount the incredible strides towards Black American literary voice made before emancipation. In fact, it aims to celebrate those accomplishments and demonstrate the legacy that they made possible.

Aims of The Crisis

In order to fully understand the larger implications of The Crisis's physical form, it is necessary for one to be familiar with some background information about this monumental publication. Founded in 1910 by the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People), the periodical aimed to help in the fight for full civil rights and against stereotyped representations of African Americans.

(DuBois, qtd. in Dzanouni) With such lofty aims less than a century since the abolition of laws forbidding African-Americans from engaging in any kind of print culture at all, the publication used everything at its disposal to make an argument for inclusion in American letters. Being temporally located at such a crucial juncture in Black history, the magazine's contents took a kind of eclectic approach, attempting to speak to every sector in African-American life. It was at once academic, and for the layman; accessible, yet elite. As Frances Smith Foster notes, early [African-American] periodicals tried to offer a smorgasbord of the practical and...scholarly...they tried to unify the various states.

(358) This mission, in all of its complexity and nuance, ultimately coded itself into the form that the texts took, which I will explore below.

A Radical Gift

The University of Pennsylvania’s rare book collection is expansive, to say the least. While the archive’s holdings include thousands of texts from a myriad of sources, one particular section holds an especially potent history for African-American material text. Donated by Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander (also known as Sadie Mossell), the collection of early editions of The Crisis is a valuable addition to the library’s catalog (Figure 1). Mosell, a notable Black scholar of the time, diligently collected the issues during her time at Penn, ultimately choosing to add them to a secure archive. Such a generous gift begs questions of form and permanence. What does it mean for a blossoming member of academe—the first woman to receive a law degree from Penn in fact—to assign value to a text like this even before she graduated? Mossell’s archival work quite literally cemented The Crisis into one of the most prestigious research institutions in the United States. How did she code that assignment of merit into the physical form of the text itself?

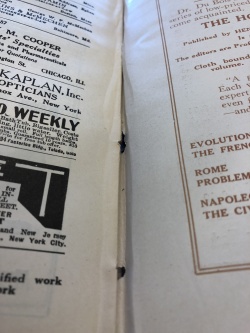

A preliminary analysis of the books themselves reveals a useful bounty of detail. The Mossell copies of The Crisis are neatly rebound in hardcover (Figure 3), moving away from the ephemeral nature of the original periodicals and into a form that calls for permanence. As demonstrated in Figure 4, original editions of The Crisis were saddle-stitched folios made with wood pulp paper, a substrate that was in vogue at the time of their publication (while the exact method used is debatable, Figure 5 provides evidence of either saddle-stitching or loop-stitching). While this format likely made distribution easy and kept costs down, it granted the publication the same gravity as any other lightweight pamphlet, making it easy for the reader to deem it disposable. The temporal consequences of such formatting are also apparent in Penn’s collection. Usage of saddle-stitching on such low-quality paper has worn holes into many pages of Volume 21, as we can see in Figure 5.

However, once Mossell’s copies were deemed worthy of official archival, their physical qualities changed completely. Most drastic is the change in binding, but other, more subtle shifts in form also communicate the goal of textual gravitas. Figure 6 notes the sprinkled red Fore-Edge_Painting along the outside of Volume 21. Since Medieval times, fore-edge treatment and decoration has been used by book-makers to denote importance and call for attention. (verch Aneirin et. al.) Although it is a small stylistic choice for a book, it is quite effective. Even nearly a century later, the speckled dots along the edge of the book caught my eye, making Volume 21 the first text that I examined. Notable as well is the fact that fore-edge treatment was used to preserve pages from temporal decay like crumbling. This is really valuable for a fragile substrate like wood-pulp paper, which is especially vulnerable to deterioration due to its high acidity. (Lewis 9) Again, the insistence on the text's permanence makes itself known, even in such minutia of the material text.

Of course, while the polished versions of these editions are intriguing, we cannot underestimate the meaning crafted into the original--yet ephemeral--pamphlets. As noted in Figure 5, the wood-pulp paper magazines are very fragile, especially given their temporal longevity. With its pages roughly half the size of a standard 8.5 by 11 inch paper, the issues are clearly meant for mobility and accessibility. In addition, 'The Crisis' functioned as a kind of curated commonplace book for African-Americans, encouraging any one of its readers to submit editorials, advertisements, or any notable events in Black history.

Meaning-Making Features

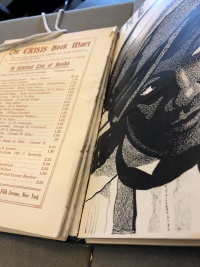

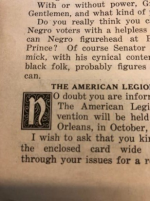

Across its early years of publication, the content of The Crisis held many intriguing features, but I’d like to focus on aspects that manipulate the material genre of the magazine to serve a social purpose. Below, I’ve included images I’ve taken of Penn’s collection of The Crisis to better illustrate my points. For the sake of comparison, I’ve also included a photo of Gutenberg’s Bible. (Figures 7, 8, and 9) Both texts mark themselves as significant through the usage of a drop cap at the start of selective paragraphs. I find this to be a particularly influential optic choice for The Crisis. As noted by David Bricker, drop caps have long been used in European manuscripts as a signifier of prestige (thus their presence in the Gutenberg text). (Bricker 1) By choosing to include this material element in The Crisis, the NAACP was—in essence—making an argument through the magazine’s physical form for the legitimacy of Black thought. As I looked through early issues, I noticed that the drop cap only appears in the Opinion piece, usually written by W.E.B. DuBois. By reserving this physical marker for those writings which the NAACP deems elite, The Crisis preserves the meaning of the drop cap, simultaneously nodding to its canonical usage and making a case for Black American letters to be included in that very same canon. All of this is accomplished before the reader even begins to consume the text’s content. Here, we witness the crafters of The Crisis taking advantage of the material tools available to them to create a space wherein Black writing is valid and legitimate.

Furthermore, at times the publication even served the purpose of record-keeping and epistemology. Catalogs like the one I’ve included of Black college graduates are some of the earliest records of their kind. (Figure 10) Upon the realization that mainstream American history wasn’t going to make space for recognition of these scholars, The Crisis reconfigured the classic idea of the magazine in order to counter hegemony. This inclusion, although seemingly small in hindsight, provided an alternative to the racist media portrayals that were in vogue for American culture during the turn of the 20th century. In the final analysis, I propose that both The Crisis’s form and content made strides in the argument for Black inclusion in print culture.

Inundating The Crisis with images like that of recent Black graduates was an especially meaningful choice given the statistics for African-American literacy during the post-Reconstruction era. In 1920, the Black literacy rate was at just 23%, 17% less than the national average. (Snyder) With inclusivity in mind, The Crisis found ways to communicate meaning through its content without always using solely the written word. By contrasting controlling images of African-Americans ruling American discourse at the time, the publication used its illustrations, both on the cover and inside, in order to cement the possibility of a successful Black future into the minds of its readership.

Modern Iterations

One of the most remarkable parts of this magazine is that it has stood the test of time to this day. Now an exclusively online publication, the modern incarnation of The Crisis certainly has the same goals as its original pamphlet form. Here, I'd like to take a moment to analyze how the magazine has adapted its approach to meet the needs of the Digital Era.

Although the prominence of the magazine has ebbed since the emergence of larger Black media outlets such as Ebony and Essence, The Crisis has maintained its accessibility, a key part of its widespread success and longevity. The main website for The Crisis is simple and informative, containing a few nods to its paper-based origins. For one, the site's homepage features a kind of digital frontispiece of W.E.B. DuBois, invoking the gravity of its founder to communicate scholarly gravitas to the reader. (Figure 11)

In fact, the entirety of the archive is now available through Google Books, a fact that would delight Sadie Mosell. (Figure 12) With the advent of color printing and ebooks, it is now far more possible than ever before to showcase accurate and considerate images of African-Americans in all facets of their livelihood. The contrast between the covers noted in Figures 11 and 4 demonstrate the nuance that The Crisis has been able to develop over time. In essence, the substrate might finally be catching up to DuBois's dreams.