From Printers to Publishers

Who are publishers? Today, they are not the ones physically applying ink to paper. Instead, they do all the work of preparing the manuscript and stop short of completing the book, sending it off to be printed somewhere else. However, the concept of a publisher as a separate entity is a recent development. When Johannes Gutenberg printed his first Bible, he was all at once editor, publisher, and printer. In this article, you can explore the gradual fashioning of an identity as a publisher that led to this becoming a separate occupation from the act of printing itself.

Aldus Manutius

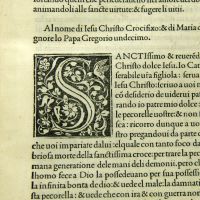

Aldus Manutius, also known as Aldo Manuzio in Italian, was a printer-publisher that founded the famous Aldine Press in the 15th century. His books were defined by their beauty and quality, including the clear Italic type used, which was easier to read and resembled the handwriting of the time. [1]

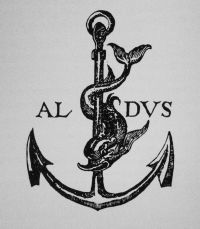

Though he mainly printed classical Greek and Roman texts, his books were meant to stand out from the others, as can be seen by the iconic colophon that marked all Aldine books, the image of the dolphin wrapped around the anchor.

Manutius was clearly concerned with the maintenance of his image and that of his Press. He stamped each of his books with his distinctive colophon, paid careful attention to the quality of the books, and had his type cutter design a distinctive Aldine typeface.[3] Manutius was extremely worried about pirates and forgers that would attempt to create counterfeit Aldine books. His colophons often threatened those who would make illicit copies, and reminded readers of the text's Papal protection. The Grolier Club has an online exhibit, Flattery and Forgery, that shows images of Aldine Press books next to counterfeit versions that tried to pass themselves off as real Aldine books. [4]

Given that Aldo jealously guarded the image of the Aldine Press, what in fact was that image? His books were curated and designed to his specifications. He stopped short of writing the texts himself (as he published both classical authors and more modern Italian works, such as Dante Alighieri or Pietro Bembo). However, he was both publisher and printer, both designing the layout, commissioning the typeface, and thinking about the overall aesthetic qualities of his books, while also physically printing these books at the Aldine Press itself. [5]

London Printer/Publishers

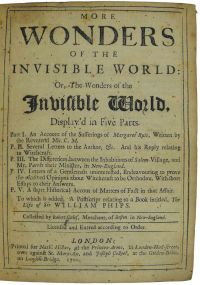

For another example of the work and role of printer-publishers, one can look to 18th century London, the stage for a great debate about copyright. Copyright debates and legislation cemented the role of printer-publishers with respect to the authors whose work they disseminated. At the beginning of the 18th century, the conceptual properties of publishing (having the right to a text, arranging its layout, distributing it) were still closely linked to the physical act of putting together the book. As was the case in Renaissance Italy with Manutius, publishers both designed and made books. A printer might request the rights to a book from an authority figure such as a king or a pope, as Manutius did. In the 1700s, printing in London was controlled by a group called the Stationers' Company. They were responsible for granting printers the rights to books.[6]

This arrangement demonstrates the powerful role of printer-publishers in this era, both as makers of books, and as keepers of the right to a book's content. By 1709, however, the Statute of Anne had been passed, placing the right to the work in the hands of the author. Thus the power of a book's making would have to be shared more evenly between author and printer-publisher, setting the stage for the more modern process for the making of a book, one that requires cooperation between an author, publisher, and printer, each independent entities that negotiate with one another in order to create a book.[7]

Post-Industrialization Printing

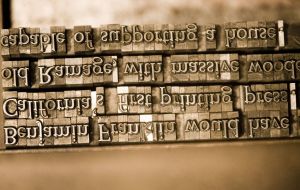

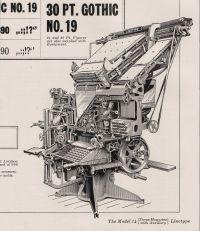

With the advent of industrialization in the early 19th century, printing became much faster and a large-scale undertaking that could produce mass quantities of books, as steam-powered printers could print up to 400 pages an hour (compared to the previous figure of 250). Johanna Drucker has a chapter in the freely accessible online text, History of the Book Coursebook, that gives a history of the industrialization of printing. Drucker details how industrial printing increasingly required huge amounts of paper and continuously evolving techniques for typesetting, including linotype, where the type would be set in entire lines at a time. [8] Perhaps the growing size and complexity of printing is what made it impossible for the previous models of printer-publishers to continue: the printer had to contend with huge, complex machinery, and a constantly increasing pace for the production of books, while publishers started to focus on the more theoretical aspects of developing a book.

Publishing and Printing Today

Today, publishers and printers take on different aspects of the job of making the book. Publishers are tasked with obtaining the rights to a certain manuscript they would like to publish, refining it until it is ready for printing, and taking on the financial risk of putting this book out into the world. Responsibilities of a publisher include editing the book in order to polish the text, designing the layout and font of the page, dealing with the legal aspects of ISBN numbers and copyright, promoting the book through marketing initiatives, and finally making sure that the book is distributed to the proper outlets. [9]

Meanwhile, the printing itself is outsourced to factories that specialize in printing books. The printer receives the order for the books and is paid for the job. The book is then printed and bound according to the request of the publisher. Crucially, the printer does not retain any of the rights to the book -- these continue to belong to the author or publisher.[10]

In this modern system, the publisher does all of the planning and designing, and the printer is seen as a less important part of the process, perhaps a "contractor" instead of a mastermind, though ironically, the actual making of the book lies in the hands of the printer who puts the words on paper and then binds these into a codex. The printer is relegated to a minor role in many ways, such as not being able to decide the design or layout of what is being printed, and significantly, receiving no rights to the book that they created. This prioritizes the content of a book over its form, where the content-makers (the author and publisher) hold all the power, free to choose from a variety of printers that have no input in the creative process. This primacy of the content of the book over its form has allowed us to make the leap from printed books to e-books and HTML text: if what matters is the words and not so much the act of printing, then pixels on a screen can be equated to a printed codex, though both objects are in fact quite dissimilar.

- ↑ TypeRoom. “Aldus Manutius: the Inventor of the Paperback Saved the Greeks with His Aldine Press Revolution.” 'TypeRoom,' Parachute, 6 Feb. 2020, www.typeroom.eu/aldus-manutius-inventor-paperback-saved-greeks-aldine-press-revolution.

- ↑ “Aldus Manutius.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2 Feb. 2020, www.britannica.com/biography/Aldus-Manutius.

- ↑ “Aldus Manutius.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2 Feb. 2020, www.britannica.com/biography/Aldus-Manutius.

- ↑ Clemons, G. Scott. “Flattery and Forgery.” Grolier Club Exhibitions, The Grolier Club, 25 Feb. 2015, grolierclub.omeka.net/exhibits/show/aldus-manutius/flattery-and-forgery.

- ↑ “Aldus Manutius.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2 Feb. 2020, www.britannica.com/biography/Aldus-Manutius.

- ↑ Borsuk, Amaranth. “Intellectual Property.” The Book, by Amaranth Borsuk, The MIT Press, 2018, pp. 84–87.

- ↑ Borsuk, Amaranth. “Intellectual Property.” The Book, by Amaranth Borsuk, The MIT Press, 2018, pp. 84–87.

- ↑ Drucker, Johanna. “History of the Book Coursebook.” History of the Book, UCLA, 2018, hob.gseis.ucla.edu/HoBCoursebook_Introduction.html.

- ↑ Ellis, Adam Ellis. “The Difference Between Book Printing And Book Publishing.” Steuben Press, Steuben Press, 10 Mar. 2018, www.steubenpress.com/blog/posts/16-the-difference-between-book-printing-and-book-publishing.

- ↑ Ellis, Adam Ellis. “The Difference Between Book Printing And Book Publishing.” Steuben Press, Steuben Press, 10 Mar. 2018, www.steubenpress.com/blog/posts/16-the-difference-between-book-printing-and-book-publishing.