Contemporary Digitization of Historic Material: Cuneiform Tablets

Background

The act of archiving can be considered primordial with respect to history. History itself can attribute almost its entirety to those who have achieved its components. However, what purpose does an object have when left to wither away until unidentifiable? How does that contribute to our understanding of the past? As any historian will exclaim, the study of the past allows for a deeper understanding of the world we live in today. Historic information offers much insight for contemporary application. The preservation of historic material is just as important as its discovery. With the proliferation of technology and data readily accessible in the twenty-first century, antiquarians and archivists are dedicatedly working to further archive and interpret historic material via contemporary digitization processes.

Cuneiform Clay Tablets

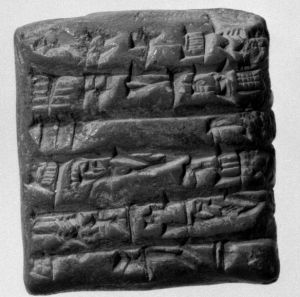

The cuneiform script, of which is written on clay tablets, is the oldest written language known to humankind. Early developments of cuneiform can be traced all the way back to 3200 B.C.E. With the use of a stylus, Sumerian scribes were able to precisely impress various triangular-esque symbols [wedges] onto a clay substrate (Anderson Archival). Such a practice was passed down and taught only to the brightest of scholars, as the required technique took much time to cultivate and perfect. Meanwhile, the art of cuneiform was a revolutionary technology with respect to its function of documentation—typically with regards to accounting and record keeping (THE EDITORS). In fact, the first known receipt resides within the substrate of a cuneiform clay tablet. Although, even once solidified, what protects these malleable clay slabs from fraud or corrosion? According to Assyriologist Dr. Irving Finkel, important information inscribed upon cuneiform tablets were often protected by yet another layer of clay as an acting envelope (Finkel). To access an enveloped receipt, one would have to carefully smash the envelope open. However, the envelopes themselves often bear information, as well, of which is also considered an invaluable component worthy of preservation. Therefore, the ultimate question surfaces: how can the historical contents of a cuneiform tablet be analyzed without damaging the contents inscribed on the substrate or the envelope?

With the help of emerging contemporary technologies, archeologists around the world have been refining digitization processes in hopes of constructing an immortal library of historic information without permanently dismantling original artifacts. Similar to sensitive medical methodologies, cuneiform substrates are examined with a “micro-CT [computed tomography] scanner” to “make a 3D reconstruction of the object” (Leiden University). Tomography is an imaging technique comprised of pulsating frequencies of certain wavelength that penetrate through the desired material. The micro-CT scanner has detectors to sense when a beam has passed through an object, thereby outlining its shape. The beam of use is most commonly known as an x-ray. The total cross-sectional analysis obtained from the summation of these lasers produces a computer-generated 3D visual. The utilization of tomography allows archivist to effectively fossilize historic material into a perpetual digital interface.

Future Significance

The act of archiving has a straightforward goal: to accurately encapsulate the breadth and width of culture in a given time period. The rich information collected can, of course, be later used to benefit or understand the society we live in. Each piece of information contributes to the overall depiction of its era. However, complete portrayals rarely exist. Ironically, the act of preservation and codification—or perhaps the lack thereof-- inherently distorts our perception of the past. Elements selected for preservation are subjectively chosen. We see only what is given to us, what is selected for us, by previous antiquarians. To a certain extent, contemporary historians are limited by the perceptions of antiquarians. These selections are supposedly wholistic and accurate representations of the past. However, there are a variety of opportunities for the distortion of historic material. An artifact could be corroded, purposely altered, unintentionally damaged, or simply poorly translated. In its documentation, an artifact is seemingly vulnerable to alteration and the fossilization of those mistaken alterations. For these reasons, it is important to read against the grain for historical archives—to look for clues of suppressed or silenced perspectives and dig beneath rudimentary rhetoric and superficial red herrings.

Fortunately, the aforementioned methods of contemporary digitization allow for a more wholistic preservation of unadulterated historic material. Cuneiform tablets and envelopes are entirely scanned and recorded to capture every detail. The entirety of its raw substrate can be safely stored in a digital cloud database forever. Historians can now completely extract and interpret the original scripts themselves, which thereby reduces external noise that may confound fresh research. The advancement of contemporary digitization technologies has significantly enhanced the efficiency and efficacy of preservation practices.

Works Cited

Anderson Archival. “What Is Historical Document Digitization?” Anderson Archival, Anderson Technologies, 13 Aug. 2020, andersonarchival.com/learn/what-is-historical-document-digitization/.

Finkel, Irving. “Irving Finkel Teaches Us Cuneiform.” Edited by Matt and Tom, YouTube, Matt and Tom, 22 July 2017, www.youtube.com/watch?v=zOwP0KUlnZg&feature=youtu.be.

THE EDITORS. “The World's Oldest Writing.” Archaeology Magazine, Archaeological Institute of America, June 2016, www.archaeology.org/issues/213-1605/features/4326-cuneiform-the-world-s-oldest-writing#:~:text=First developed around 3200 B.C.,shaped indentations in clay tablets.

Leiden University. “Seeing through Clay: 4000 Year Old Tablets in Hypermodern Scanner.” YouTube, Universiteit Leiden, 24 Apr. 2018, www.youtube.com/watch?v=5RmTpMoH-1o.